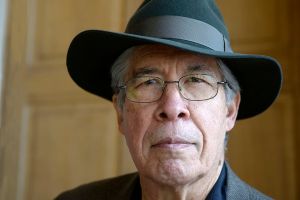

‘Hi, it’s Jonas.’ When the great tenor rings from Vienna, I ask if there are any topics he wants me to avoid, such are his minders’ anxieties. ‘Ask anything,’ laughs Jonas. ‘I’m not shy.’

He is heading in from the airport to see a physio — ‘these concerts, you have to stand there all the time’ — before taking Hugo Wolf’s Italian Songbook on a seven-city Baedeker tour: Vienna, Paris, London, Essen, Luxemburg, Budapest, Barcelona. I wonder if he is aware that Wolf is a hard sell to English audiences. ‘Not just the English,’ he replies. ‘Even in Germany promoters say to me, please don’t do a Wolf-only recital, no one will buy tickets. People don’t know Wolf, so they are afraid of it.’ They shouldn’t be, he says. ‘Wolf is a fantastic composer, never too heavy, he ought to be as acceptable as Schumann or Brahms.’

The foremost German tenor since Fritz Wunderlich, Kaufmann’s presence or absence can make or break a season. His cancellations, which are not infrequent, come with more detailed explanations than the usual ‘indisposed’. Kaufmann agonises over causing inconvenience. ‘When I cancel, I am punishing myself,’ he says. ‘I know singers who hate to sing. They do it because people pay them for it. For me, it’s the absolute opposite. If nobody turned up I would still want to sing. It’s not easy to cancel. I know how many people have gone to trouble to hear me.’

In the past year he twice pulled out of the Four Last Songs of Richard Strauss and tongues began wagging about a jinx. Strauss, who mistrusted tenors, asked for his deathbed cycle to be premièred by Kirsten Flagstad in 1950 and the set has belonged to big sopranos ever since. Was Kaufmann not being greedy by coveting the songs, maybe tempting fate?

‘Both times I cancelled I had a cold,’ he says prosaically. ‘Maybe if I had swallowed lots of chemicals… I didn’t want to risk anything.’

His reason for performing the songs was provided by a musicologist friend working at the Strauss archives. ‘My friend saw the autograph score of the Four Last Songs. The printed score says “for soprano”. The composer’s autograph says “for high voice”. My friend said, “This is something you could take on.”’ The set has been rescheduled for the Barbican in May. ‘Hopefully,’ says Jonas Kaufmann.

Like Anna Netrebko among sopranos Kaufmann stands alone at the summit of his Fach. Getting there was not easy. He spent most of the 2000s under contract at Zürich Opera. ‘Zürich was a safe harbour for me to try out roles in a friendly environment. It was also insurance. If you got sick you still got paid. But it was not a typical treadmill slavery contract. I sang Mozart roles, Schubert’s Fierrabras, Fidelio, Verdi — Don Carlos, Rigoletto, Traviata.’ Prepared to take his time, Kaufmann was almost 40 before he hit the world circuit.

He feels most comfortable these days in Paris and at Covent Garden, ‘just because of Tony [Pappano], everybody wants to sing with him. God knows what will happen when he’s gone.’ His home base is Munich, though he frets for its future once the music director Kirill Petrenko moves on to the Berlin Philharmonic. ‘Kirill is one of the very few — with Tony Pappano and Andris Nelsons — who really know about singers. Such a pity he wants to focus on the symphonic repertoire.’

Kaufmann makes no secret of his discomfort with New York’s Metropolitan Opera. ‘The productions have not always been that great. The HD [cinema screenings] are a big success but many people don’t see the need to go to the show in New York any more. These people are not going to come back. The Met can’t even sell out a Tosca.’ When Kaufmann, missing his children in Munich, tried to shorten his run in the Met’s ill-starred Tosca, he was ‘disturbed’ to read in the New York Times that he had cancelled. ‘It was not a cancellation from my side. I asked for a reduced rehearsal period and fewer performances. But they wanted all or nothing,’ he explains. He hates to be seen as a shirker.

America’s sexual harassment hysteria has left him confused. I ask if he was ever targeted by predators. His response is swift and confessional. ‘When I was a student,’ he relates, ‘there was a promoter who offered me a concert in his series, which would have been fantastic for me. But the obvious exchange, and he was very specific, was for me to go with him to a sauna club, rent a cabin and give a full body massage.

‘I was 20 or 22 and I understand that if you think this is your chance you probably think, go for it. But I didn’t. I was really, really scared.’

He fears the pendulum has swung too far the other way. In Santa Monica recently he was about to sing a popular Richard Tauber encore, ‘Girls are Made to Love and Kiss’, when he wondered if this was still safe. ‘If I have to ask myself whether these tiny little erotic hints that composers gave in the 1920s are inappropriate, half of our operatic repertoire can’t be played any more. And it’s hard. We have so many people living alone because they cannot find a way to approach someone.’

Kaufmann, 48, is (he assures me) not single. After the end of a long marriage to the mezzo-soprano Margarete Joswig, he formed a relationship with Christiane Lutz, an opera director. They seem happy.

Ten months of the year he is on the road, waking up each morning to test the voice, aware that thousands depend on its state of health. After two rocky years, he is cautiously confident. ‘I believe the voice is still quite fresh,’ he volunteers, with clinical objectivity. ‘It feels like there are no limits. I have the impression I can go on for a very long time.’

Jonas Kaufmann is touring Wolf’s Italian Songbook with Diana Damrau and Helmut Deutsch and will present it at the Barbican on 16 February.