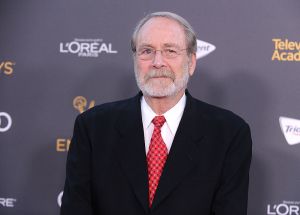

In ‘A Prize for Every Player’ — one of 12 stories in Days of Awe, a new collection by A.M. Homes (Granta, £14.99) — Tom Sanford, shopping with his family in Mammoth Mart, soliliquises (loudly and nostalgically) about the America he remembers, and finds himself with an audience of shoppers who nominate him as the People’s Candidate for President. Absurd? Not quite so absurd perhaps as in pre-Trump days.

Days of Awe (the title comes from Rosh Hashanah, the ten days of repentance in the Jewish calendar) is Homes’s third collection and her first book since winning the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2013. The stories balance on a narrative tightrope between reality and absurdity, taking the anxieties of the American elite to a satirical extreme. It makes for a thought-provoking read.

Two stories, ‘Hello Everybody’ and ‘She Got Away’, feature a dysfunctional and decadent LA family, obsessed with diet and plastic surgery. (Even the dog has surgery for ‘an unappealing fatty tumour.’) Out for a meal, the family request items of ten calories. Witty and tragic, the stories focus on sisters Cheryl and Abigail — characters Homes has written about in earlier stories.

‘Be yourself,’ Cheryl advises her sister. ‘I’ve no idea how to do that,’ Abigail replies. Ultimately Abigail dies of anorexia. Planning her funeral, Cheryl says: ‘I don’t think she’d like to be in a coffin… She would think a coffin made her look fat.’

These stories are concerned with the public and the private, the physical body and inner self. Dialogue drives them all. In the title story, a war reporter and a novelist meet at a conference on genocide: the reporter is haunted by the deaths he’s seen, the novelist by her fictional reliving of the holocaust. They come together in a slightly violent affair to escape the pain or guilt of knowledge acquired (by witness or imagination) rather than lived. The effect of war on subsequent generations haunts most of these stories. The cleverest use of dialogue comes in ‘The National Cage Bird Show’, set in a chat room for lovers of budgies and in which a soldier recounts his war experiences and a teenage girl tells of abuse. (Others discuss bird food!)

In comparison to Homes’s diverse and thoughtfully considered collection, Joseph O’Neill’s Good Trouble (Fourth Estate, £12.99), seems rather casually gathered from stories published mainly in the New Yorker or Harper’s in the ten years since he was shortlisted for the Man Booker with Netherland. They’re immensely readable, about exasperating and ultimately feckless and disappointing men. Give us a break, you want to say by the time you get to the 11th and final story. Actually it was this one, ‘The Sinking of the Houston’, that really got to me. How could I be so gullible as to believe that this father of sons (‘you don’t mess with my children’) is really going to go out and get the thug who’s mugged one of them?

In ‘The Referees’, Rob Karlsson is so poorly regarded that he can’t find anyone to give him a reference and ends up writing his own. In ‘Ponchos’, a wannabe poet compares the fish in a San Francisco roundabout aquarium to the human condition — ‘beings without the slightest prospect of progress, illumination or salvation’. ‘The Poltroon Husband’ concerns a man who, hearing the sounds of a potential burglar downstairs, is overcome by a ‘an oneiric paralysis’ that keeps him in ‘psychic captivity’, i.e. in bed.

Oh they’re funny all right, these O’Neill guys, with their ‘if onlys, why-oh-whys, and where is she-nows’ (‘Ponchos’) but en masse they become a little tedious.

Christine Schutt’s collection Pure Hollywood (And Other Stories, £8.99) comes with an endorsement from George Sanders. Not much cheer here, with 11 stories of loss, grief and dysfunctional families. But the writing is slick, poetic, niftily condensed. Meet Bob Cork, ‘a lean, hempen, homiletic man, worn as his old jeans — duct-taped sandals, cork-screw pony tail’ from ‘Species of Special Concern’. The characters are depressing, the most upsetting being Lolly who can’t stand her child (‘The Hedges’) — but there’s an added grace: Schutt, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, writes beautifully on gardens. Take this clematis, described as ‘not a thug, but a racer on a brittle stem’ (‘The Duchess of Albany’).

Charco Press, a new independent publisher of Latin American novels in translation, has brought out an ambitious amalgamation of one novel, one novella and a batch of short stories by Margarita García Robayo, the whole given the umbrella title Fish Soup (£9.99). More stories of dysfunctional families, but told with magic realism, energy and eroticism. The strongest is ‘Sky and Poplars’, about a woman who goes home, after losing both her baby and her lover, to a crass mother and a father who hides in the shed. ‘Worse Things’ is a terrifying tale of obesity.

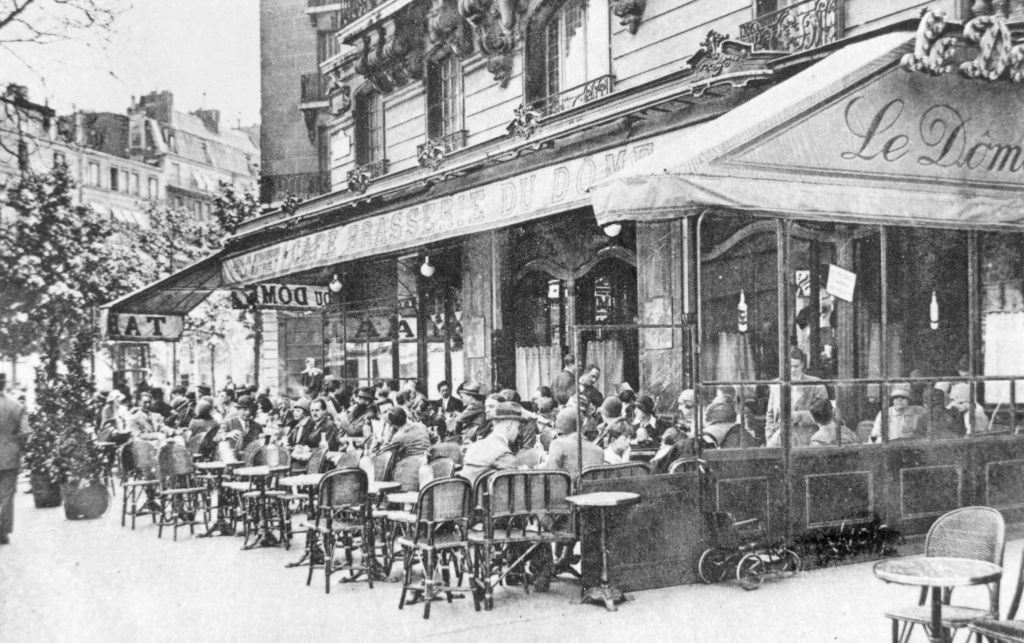

If I had to keep only one of these five collections it would be The Beggar and Other Stories by the Russian émigré Gaito Gazdanov (1903–1971), published for the first time in English by Pushkin Press (£12). Translated with an introduction by Bryan Karetnyk, these six stories deal with the mystery and meaning of life. In ‘Ivanov’s Letters’, the main character declares: ‘Everyone, or nearly everyone, is interested not in how he lives, but in how he wants or ought to live.’ A sound basis for any short story.

After so much American angst, these tales, in which characters face life with a balance of despair, courage and joie de vivre, are a refreshing delight.