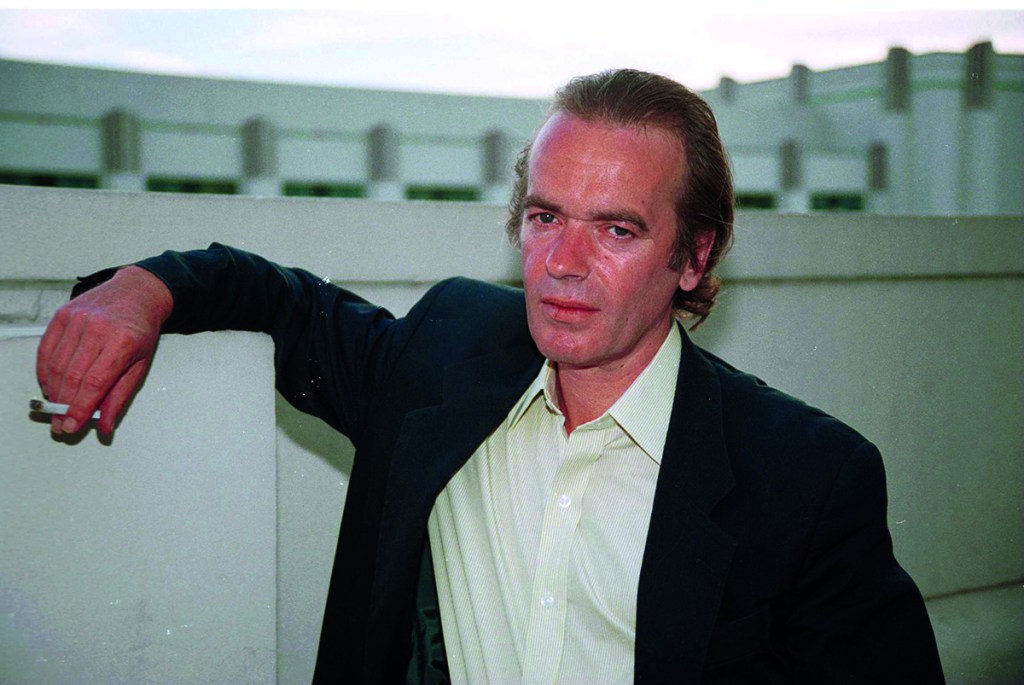

It is one of those cosmic ironies that the author Martin Amis, who has died at the age of seventy-three of esophageal cancer, might have appreciated that his death was announced the day after Jonathan Glazer’s adaptation of his novel The Zone of Interest premiered to a rapturous reception at this year’s Cannes film festival. In truth, Amis, despite being a fully paid-up cineaste, had never been served particularly well by the cinema before; adaptations of his novels The Rachel Papers, Dead Babies and London Fields – the latter co-written by him, and with a cameo by the ever-controversial Cannes returnee Johnny Depp – were all seen as somewhere between poor and disastrous, and the sole screenplay that he wrote, for the sci-fi picture Saturn 5, was seen as a strange anomaly in an otherwise glittering career.

Yet Amis will be missed not for the occasional forays that he made into film, but for a literary legacy that, despite going off the boil somewhat in recent years, remains one of the most distinctive and distinguished of any twentieth-century British novelist. He was, of course, born with a famous name, and often made disparaging remarks about how his career, following that of his legendary father Kingsley, was little more than continuing the family business – one joint biography of the two men is simply entitled Amis and Son, as if they were tradesmen – but he swiftly marked himself out as a distinctive, inimitable talent, who, at his best, managed to bring a contemporary Swiftian wit to the state-of-the-nation satires that enraptured readers on both sides of the Atlantic.

There will inevitably be debate over which Amis’s finest novel was – for my money, it doesn’t get much better than his Eighties satire Money, although it is possible to make a decent argument for London Fields, Success or even his debut The Rachel Papers – but it’s also important to remember that he was a non-fiction writer of rare talent, too. His memoir Experience, in which he writes about everything from his father to the death of his cousin Lucy Partington, murdered by the serial killer Fred West, is a masterclass in unsentimental, brilliant prose; as a critic, Amis was incisive, often unsparing and peerlessly witty. And his final “novel” Inside Story – in effect, a lightly fictionalized memoir – contained affectionate but pointed pen portraits of everyone from his godfather Philip Larkin to his closest friend Christopher Hitchens, and reminded his readers that Amis was one of the last members of a rapidly vanishing literary tradition that seems unlikely to be recaptured.

Amis may have seemed a quintessentially British writer, but he ended his life at home in Lake Worth in Florida, after having lived in America for many years. He spent time living in a brownstone “sock” in Brooklyn, where he associated with the likes of his fellow expatriate Salman Rushdie, and Hitchens, during the final years of the latter’s life. He wrote about the United States with a clear-sighted view that combined affection with amusement at some of its excesses – not for nothing was one collection of essays about the country called The Moronic Inferno – and he was regarded in turn as a distinguished adopted son. He will be greatly missed in just about every English-language speaking nation, and well he should be, given that he was one of the most inimitably witty and, when on song, brilliant authors of his time. His death – like Hitchens, gathered before his time – puts an end to “the Amis dynasty,” something that he may have railed against on occasion, but remains one of the most distinctive and purely enjoyable literary legacies of the century. He shall, and should, be missed.