“Most of my heroes are monsters, unfortunately,” Joni Mitchell once said, “and they are men.” The singer-songwriter was able to detach the maker from the made. Should we do the same? Is it ethical? Even possible? These are the questions Claire Dederer deftly considers in Monsters, which puzzles through the problem of what we ought to do about great art by bad men.

Ideally, nothing. Early on in her quest, Dederer longs for someone to invent an online calculator:

The user would enter the name of an artist, whereupon the calculator would assess the heinousness of the crime versus the greatness of the art and spit out a verdict: you could or could not consume the work of this artist.

Alas, said calculator has yet to be programmed, so it’s down to her to do the maths.

Part biography of baddies, part examination of the audience (who, spoiler alert, aren’t always goodies), Monsters is divided into chapters that consider contributing factors such as the fan, critic and genius. First up, the seed of the book: the child rapist. It was while researching Roman Polanski for another writing project in 2014 that Dederer tried to solve the issue of admiring someone who had done a terrible thing (in Polanski’s case, rape a thirteen-year-old). “I wanted to be a virtuous consumer, a demonstrably good feminist, but at the same time I also wanted to be a citizen of the world of art.”

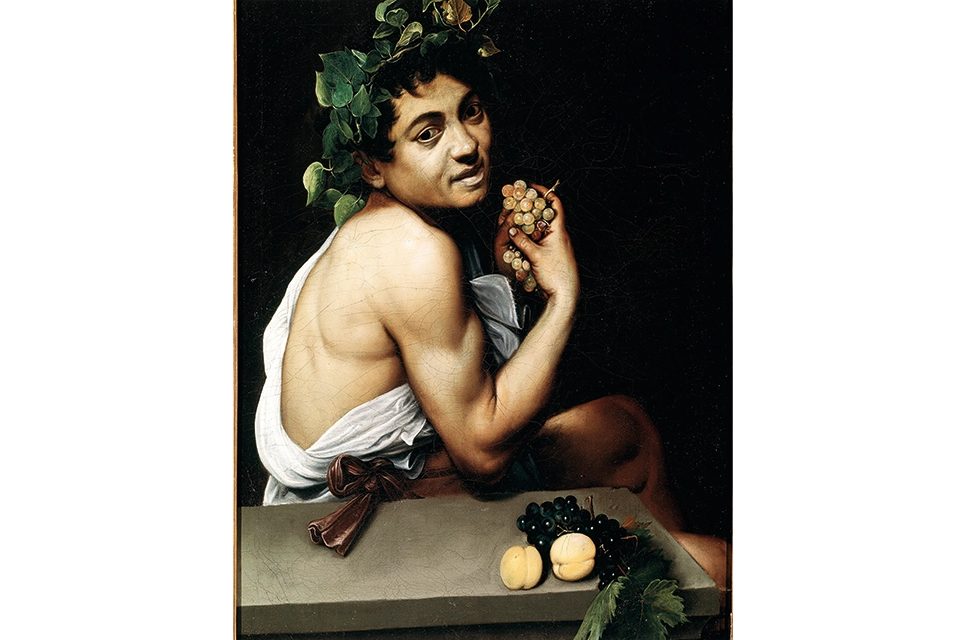

She started keeping a list of offenders: Caravaggio, Bill Cosby, Norman Mailer. “Add your own — add a new one every week, every day,” she writes in characteristically chatty, candid prose. Monstrous men are nothing new, but after Trump’s Access Hollywood tape dropped in 2016, and the Weinstein story broke the following year, the #MeToo movement that had been simmering for a decade reached boiling point and there was a “collective rage-fest.” The conundrum Dederer had been pondering in private became public debate.

The reckoning coincided with what she describes as a “movement towards knowingness.” Thanks to social media and the internet, information on artists is readily available; in other words, “everything is everyone’s business.” The trouble is, the more we know about a maker, the closer we feel to them, and the more we are disappointed by — even implicated in — their misdeeds. One chapter charts the rise of cancel culture and the subsequent tribulations of, you guessed it, J.K. Rowling.

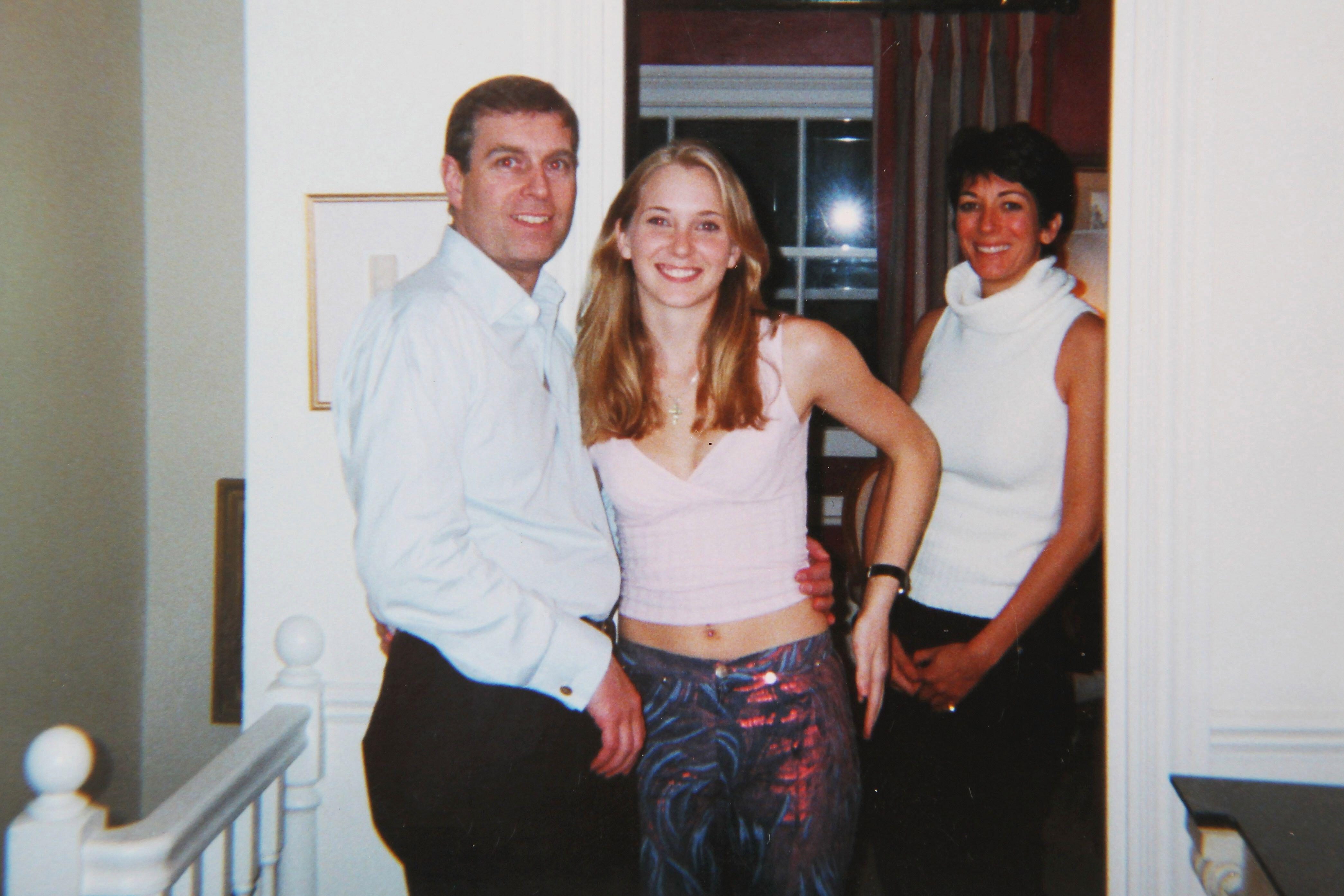

Who else? There’s Woody Allen — “the person who engendered the most soul-searching in the average audience member.” And Michael Jackson. Breakfasting in a diner, Dederer finds herself bopping along to ‘I Want You Back” by the Jackson 5, yet “the moment was ruined.” The song, and her experience of it, is irreparably stained by the artist’s biography, and by her own too.

It’s not just monstrous men who are in the spotlight but the language surrounding them. The words “monster” — “balls-out, male, testicular, old world” — and “genius”: that special designation that “informs our idea of who gets to do what.” The genius, writes Dederer, is “immune to the stain.” Enter Picasso and Hemingway. Men at the mercy of their art. Heaven forbid they constrain themselves in life, lest doing so accidentally dims their creative light.

There are monstrous women, too, though their crimes are less heinous. Aside from Virginia Woolf, whose diaristic writings are dotted with antisemitic remarks, and Valerie Solanas, who shot Andy Warhol, the monstrousness of females, Dederer argues, has less to do with abuse and more to do with motherhood. “If the male crime is rape,” she writes, “the female crime is the failure to nurture. The abandonment of children is the worst thing a woman can do.” Turning the lens on herself (which she does often and unflinchingly) she pinpoints “the small human abandonments” she has performed over the years in order to write.

Which brings us back to Joni Mitchell, who, in 1965, aged twenty-one, an unmarried art student and aspiring singer, fell pregnant. She had the baby and gave it up for adoption, which freed her to become a star. She looked to Miles Davis (domestic violence) and Picasso (rampant misogyny) for models. “For Mitchell, separating the life from the art was not an aesthetic question but a point of view necessary to her survival.” In that way, writes Dederer, “I am like her. Just trying to figure out how to do it.”

Aren’t we all, as we stand in front of “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” or settle on the sofa to watch Manhattan? In this book you may not find the answer, but you will find heaps of wit and wisdom — on monsters, victims, hate, love and the big gray area in between. One thing’s certain: “The way you consume art doesn’t make you a bad person, or a good one. You’ll have to find some other way to accomplish that.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.