I am undoubtedly, alas, an example of what the Fowler brothers, H.W. and F.G., of The King’s English fame, would have called ‘a half-educated Englishman of literary proclivities’. Fellow half-educateds of similar proclivities will doubtless recall that scene in the third chapter of Our Mutual Friend, when Gaffer Hexam shows Mortimer Lightwood and Eugene Wrayburn the handbills of the missing persons that he has pasted all over his wall:

He waved the light over the whole, as if to typify the light of his scholarly intelligence. ‘They pretty well papers the room, you see; but I know ’em all. I’m scholar enough!’

For Gaffer’s handbills, I have my copies of books by Niall Ferguson, Tristram Hunt, Neil MacGregor and the like, which I proudly flaunt in my bookshelves, in the vain hope that they might somehow illuminate my dim understanding of history, culture and the great wide world beyond my teeny tiny and immediate grasp. Violet Moller’s The Map of Knowledge is another such lamp unto my feet and a light unto my path.

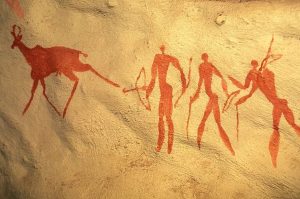

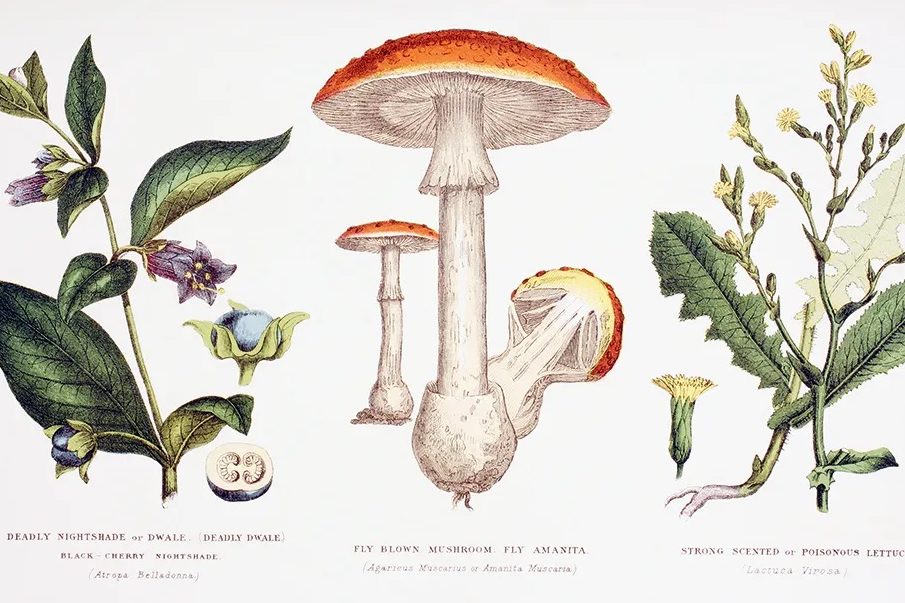

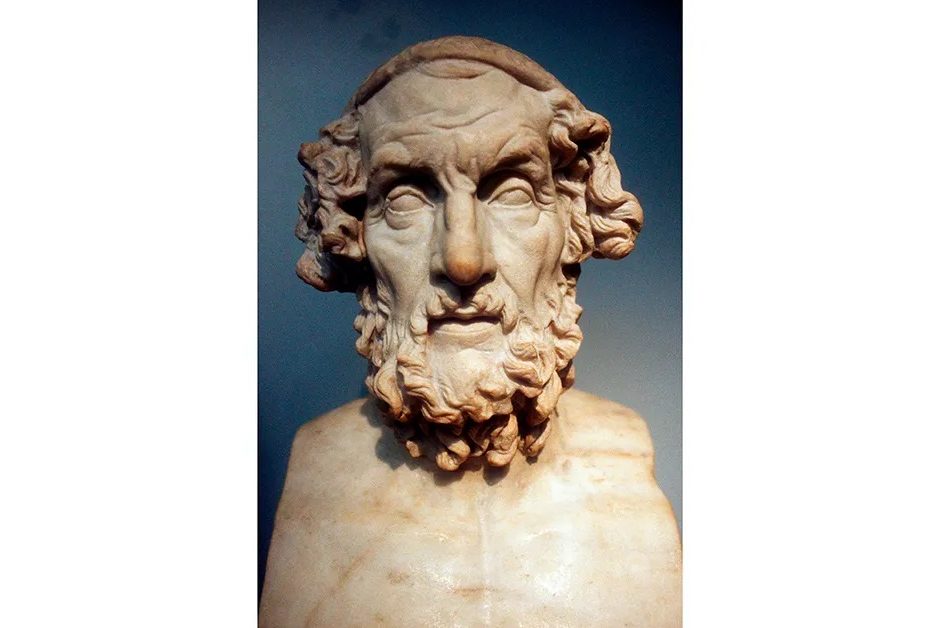

Moller’s simple, massive aim is to show how the works of Euclid, Ptolemy and Galen in mathematics, astronomy and medicine spread throughout the Islamic world and in medieval Europe. She follows the fate of The Elements, The Almagest and Galen’s vast corpus as they are variously translated, transported and disseminated through Alexandria, to Baghdad, Córdoba, Toledo, Salerno, Palermo and on to Venice.

The book is an ambitious work of popular history, and not unaware of its contemporary relevance and themes:

Each of the cities we have visited in this book had its own particular topography and character, but they all shared the conditions that allowed scholarship to flourish: political stability, a regular supply of funding and of texts, a pool of talented, interested individuals and, most striking of all, an atmosphere of tolerance and inclusivity towards different nationalities and religions.

Yeah, get it? Historians will perhaps find nothing new here: this is not original research but sweeping synthesis, narrated in omniscient voiceover style.

If you could look down on the Mediterranean world in the year 500, what would you see? An Ostrogoth king on the throne in Rome, doing his best to look like an emperor. An emperor in Constantinople, recreating the glories of imperial Rome on the shores of the Bosphorus, and, far to the south, in the very cradle of civilization, a Persian shahanshah, plotting his next move in the interminable war on his northern borders.

Moller writes like a tour guide on a very expensive cruise: ‘Meanwhile, across the Ionian sea, on the rocky hilltop of Montecassino in South Italy, a pious young Christian called Benedict founded a monastery.’ ‘But first we need to go back in time, to the very beginning, when Euclid, Ptolemy and Galen sat down to write their books.’ If you’re not a fan of such an approach — and to be clear, I definitely am — then you might be better off sticking to the standard academic texts on the history of science in the ancient world and the Middle Ages.

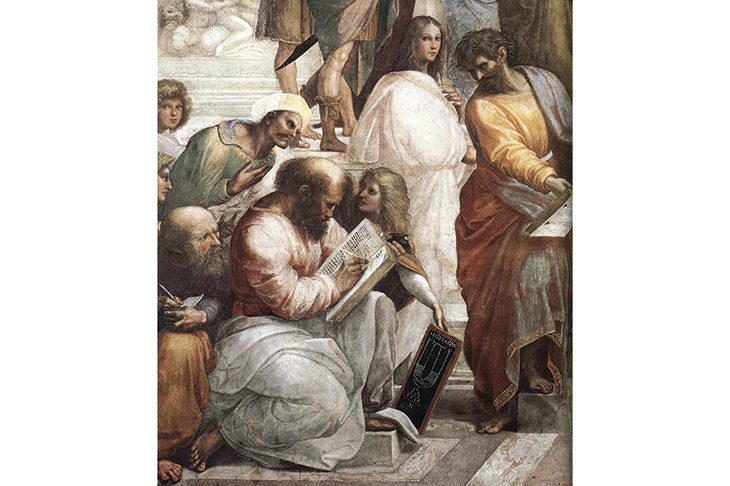

What Moller does that your average OUP or your CUP history or companion most certainly does not do is to imagine vivid scenes and scenarios and to populate them with colorful historical figures thinking big, bold, beautiful ideas: basically, The Map of Knowledge is a Peter Ackroyd, written by Bettany Hughes. The book boasts a cast of thousands, from the great al-Mansur founding Baghdad, to the Banu Musa brothers (a trio of eccentric geniuses, famous for their Book of Ingenious Devices), to the translator Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Aldus Manutius with his printing house, and Hypatia, famed as the first great female mathematician.

As a half-educated etcetera etcetera, I have read a few books that touch upon some of the areas explored by Moller — Jim Al-Khalili’s excellent The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance, for example; Catherine Nixey’s recent The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, David Abulafia’s amazing The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean — but I have to confess that I knew little or nothing about the rise and fall of Salerno as a centre for the study of medicine, or indeed of the history of the Mozarabs in Toledo, who played a central role in the translation of texts and ideas from Arabic to Latin. Moller makes lots of connections and fills in many gaps.

It would be true to say that as the book progresses, it seems to diverge from its original purpose, and of the initial inspiring trio — Euclid, Ptolemy and Galen; but if The Map of Knowledge is a book that loses its way in its own enthusiasms, it nonetheless manages to carry you along with it. Thucydides of course wrote not to please the taste of the immediate public, but for all time: as a representative of the immediate public, I’m rather glad that people like Violet Moller are prepared to provide for the likes of us.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.