Turkey greets you with a chilly blue eye, a flared eyebrow, a cliff-like cheekbone. The face of the republic’s founder glares imperious from almost every office wall, shopkeeper’s kiosk and airport terminal.

Turkish citizens regard Mustafa Kemal reverentially: the nation’s first president, courageous leader of the 1919–1922 war of independence, deliverer from the great powers’ imperial cleaver. An impenetrable cultish mythos envelops him. Even for Istanbul’s young cosmopolitans, any word against Kemal spurs a visceral reaction. Recep Erdogan, the current president, whose politics are anathema to Kemalist ideology, still has to invoke him for the purposes of propaganda. To an American intelligence officer who met the man in the fraught summer of 1921, however, Kemal was a ‘clever, ugly customer,’ with the look of ‘a very superior waiter’.

It’s little wonder that an American would view Kemal in such a way. His nationalist movement was waging a quasi-guerrilla insurgency against the victors of the first world war, who sought to carve up the moribund, defeated Ottoman empire. In the process, Kemal completed what his predecessors had already begun: the definitive slaughter and removal of the empire’s remaining Christian population: Pontic and Ionian Greeks, Assyrians and, of course, Armenians.

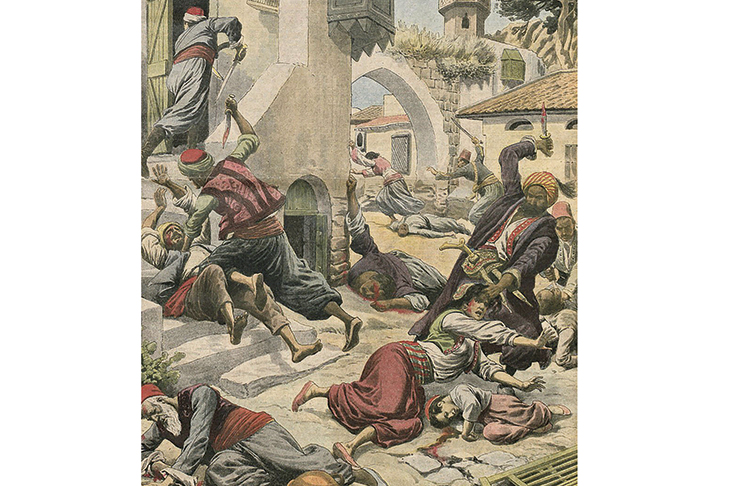

In their expansive and detailed new volume The Thirty-Year Genocide the historians Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi depart from well-established accounts of the Armenian genocide which often consign earlier and later frenzies of slaying to introductions and conclusions. They roll three crimes into one. First, the Hamidian Terror (1894–96) under the sclerotic rule of Sultan Abdülhamid II. Secondly, the obliteration carried out by the formerly liberal Committee of Union and Progress (1914–18). And finally, the Kemalist ‘cleansing’ campaigns during and after the war of independence (1919–24).

Morris and Ze’evi document each period well, if often gruelingly. They include a distressing but accurate summary:

‘An Armenian woman from eastern Anatolia, born in the 1880s, would likely have seen her parents killed in 1895 and her husband and son massacred in 1915. If she survived, she probably would have been raped and murdered in 1919–1924. Certainly she would have been deported in that last genocidal phase.’

They are right to draw a link between all three in the sense that, no matter the ideological motive, the result was the same: a complete eradication of ethnic and religious minorities, leading to a death toll that approaches two million. But it is the ideological motives that the authors encounter trouble with. To their credit, they admit that ‘the bouts of atrocity were committed under three different ideological umbrellas’. Yet for their thesis to work, there must be unity of purpose. And they’ve picked the wrong one.

They find an ‘overarching… banner’ in Islam, which, they say, ‘played a cardinal role throughout the process’. Partly, their misreading is down to relying extensively on the accounts of Allied officers or western missionaries quick to attribute bouts of savagery to ‘fanatical Mohammedanism’. This skips over the fact that ‘Christians lived in relative security under Ottoman rule for centuries’. What changed?

The only theory that could explain all three fits of carnage is this: a siege mentality. Abdülhamid II, the Committee of Union and Progress and Mustafa Kemal (also a CUP member) were all gripped by a fear of the state’s disfigurement and collapse, and they directed apocalyptic violence against those they perceived as traitors or fifth columnists.

Indeed, only this could explain something Morris and Ze’evi consign to a desultory footnote: the Turkish republic’s 94-year-long campaign against the Kurds. They are Muslim, too, by majority, but from 1925 engaged in rebellions and resistances against the state — and have suffered dearly for it. In a way, paranoia about partition is the galvanizing politics of the Turkish elite to this day.

The authors also withdraw from a bitterly ironic point made by pioneering writers such as Taner Akçam, Ugur Üngör, and Hrant Dink, a very confronting and uncomfortable idea indeed: contrary to the miraculous or messianic view of Mustafa Kemal, there would not be a Turkish nation without the destruction of its Christian peoples. The very foundation of republican Turkey is an abattoir of mud and blood.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.