Sunset

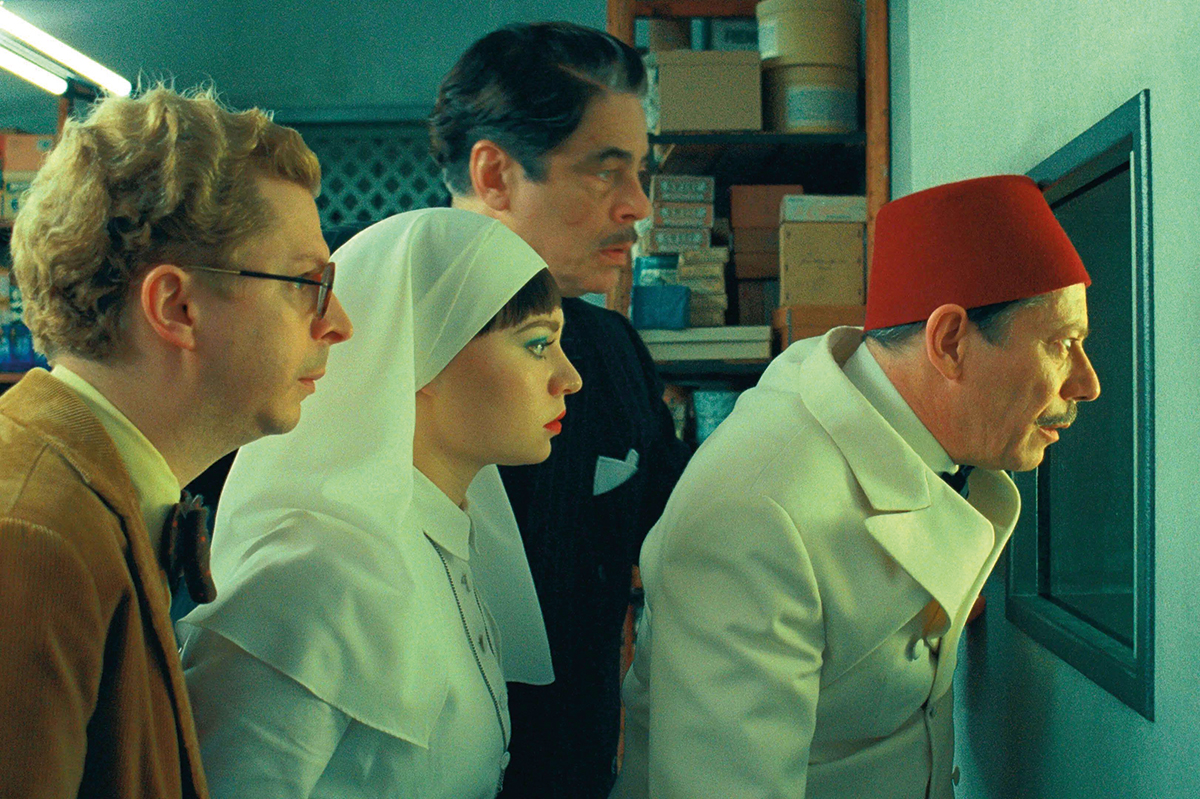

is French-Hungarian writer-director László Nemes’s follow-up to his astonishing Oscar-winning debut, Son of Saul. This time around the film is set as the Austro-Hungarian Empire is on the brink of collapse, and it is confounding, but not in a good way, as it’s as turgid as it is baffling. I’ve seen it twice now, and it was as turgid as it was baffling on both occasions. Disappointing, I know, but on the plus side the backdrop is a high-end millinery establishment, so the hats are fab. Truly.

It opens seductively enough, in bustling Budapest in 1913. It opens as if this were a Dickens or Dostoyevsky, but it’s not that type of costume drama, alas, so best get that out your head. Here, we find a beautiful young woman trying on a hat in the millinery establishment Leiter’s. We think she’s a customer initially, as do the staff, but this is Irisz Leiter (Juli Jakab), whose parents owned the shop until it burned down when Irisz was two, taking them with it. This much, at least, is clear. The new owner Brill (Vlad Ivanov) is not happy to see her. What does she want? Reparation? This is what we are asking ourselves, but the question is never answered. She says she’s solely after a job. Brill refuses and then retracts the refusal. Brill is sometimes paternal and kindly and sometimes stern and harsh. Brill says go away and then puts her up at a hotel. At no point does any character own their behavior in any consistent or recognizably human way. Which is trying, and also makes it impossible to engage. Why connect with these people who may behave one way and then another, with no rhyme nor reason?

Irisz learns that she has a brother. She learns this when roused in the middle of the night by some crazy-eyed bearded fella — there are quite a few crazy-eyed bearded fellas; it is hard to keep track of which one is which — who then jumps out the window. This is intriguing, but what follows is, essentially, nearly two and a half hours of following Irisz — who is unreadable throughout — from one incoherent scene to the next as she searches for this sibling. Mostly, these scenes don’t lead anywhere and involve Irisz being told to clear off, sometimes accompanied by the threat of sexual violence. The other characters she encounters feel like stock types: an evil Viennese aristocrat, an emotionally deranged countess. And everyone talks in riddles. ‘It’s starting again,’ someone might say. What? What’s starting again? ‘Blood will flow this week,’ someone else might say. Why? Why will blood flow this week? A film does not require logic or a narrative that is certain. It can work directly on the emotions, like music. Or it can be about atmosphere. Fair play, this does conjure a mood of ominous dread, but it is so turgidly repetitive — ah, here comes someone else to say something enigmatic — it feels as if there is no proper development of any kind. You know as little about Irisz at the end as you did at the beginning.

And, throughout, we are yoked to Irisz’s head. That is, Nemes’s camera rarely strays from the back of her neck. It is a pretty neck. I wish I had such a neck. But this lack of peripheral vision, which worked amazingly well in Son of Saul, seems merely like a conceit too far here. Some will read all manner of allegory into this — it’s about Europe today being on the brink of disaster — but I didn’t get any of that, I have to say. Good hats, though. No quarrel there.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.