For me, a home without Period Piece is like a house without a cat — lacking an essential cheering and comfortable element. I have loved Gwen Raverat’s memoir of growing up in Cambridge in the 1890s ever since I first read it 20 years ago when recuperating from a bad bout of ’flu, at that blissful moment when you are feeling better but not quite strong enough to get up and do anything. I can still recall the delicious feeling of reading and dozing, dozing and reading, snug in the gas-lit world of Victorian Cambridge, until the January afternoon outside the bedroom window gradually turned purple and faded into dark.

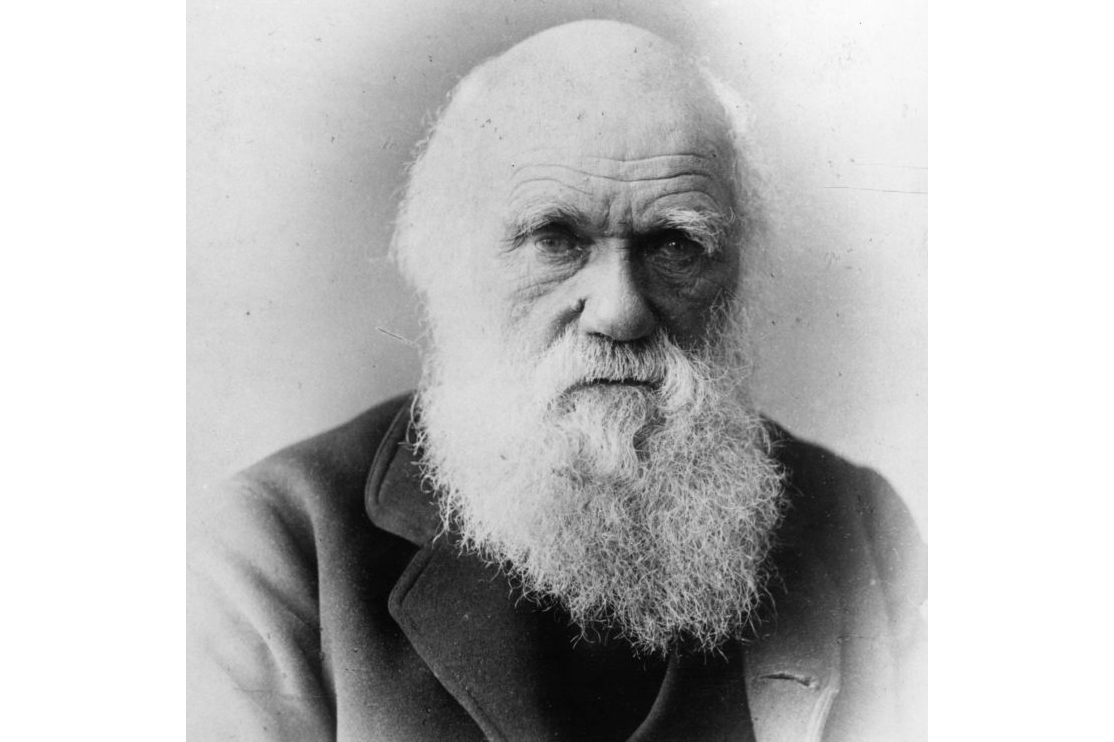

In fact Gwen’s family the Darwins (Gwen’s paternal grandfather was Charles Darwin) had a very particular relationship with illness, being total hypochondriacs, and ill health – or rather the lack of it – features prominently in the book. Her much loved Aunt Etty, for example, was only 13 when, after a ‘low fever’, the doctor recommended she should have breakfast in bed for a time, and she never got up for breakfast again. When there were colds about she would put on a protective mask of her own invention, made from a wire kitchen strainer stuffed with antiseptic cotton-wool and tied on like a snout, from behind which she would discuss politics in a hollow voice, oblivious of the fact that visitors were struggling with fits of laughter.

Like many Victorian women, childless Aunt Etty had never even had to make a pot of tea for herself, and had very few real outlets for her abundant energy (‘she could have ruled a kingdom with success’, observes Gwen), so a great deal of it was concentrated on the health of her husband, Uncle Richard. Poor Uncle Richard, it seems, had not originally been ill, but Aunt Etty had decided that he was extremely delicate ‘and he was very obliging about it’, eating up his doses of Benger’s Food (known to the children in the family as ‘Uncle Richard’s porridge’) like a man. And ‘if a window had to be opened to air the room in cold weather, Aunt Etty covered him up entirely with a dust sheet for fear of draughts; and he sat there as patient as a statue, till he could be unveiled’.

Uncle Richard was very much a man of his time. He adored Ruskin, worshipped Morris, taught at the Working Men’s College and slept for years with a volume of Tennyson’s In Memoriam under his pillow. I feel he would have enjoyed the coincidence of my reading about the Darwins’ ailments while ill in bed myself, for at concerts he loved to read certain passages of Greek plays while listening to particular pieces of music. Apparently ‘a triumph of timing occurred once, when he was listening to the thunderstorm in the Pastoral Symphony, and reading the thunderstorm in Oedipus at Colonus, and a real thunderstorm took place!’

Gwen’s own father, George, shared the Darwin propensity for mysterious and unidentified ailments, but happily, in his case, marriage actually improved his health. He had fallen in love with Gwen’s American mother, Maud, when she was visiting her glamorous Aunt Cara, wife of the future Professor of Greek at Cambridge, Richard Jebb, and the two had married in 1884. They settled at Newnham Grange, an old mill house on the Backs, which was romantic though damp, and in the early days, when all Cambridge’s sewage still drained into the river, distinctly smelly. It’s said that when Queen Victoria was being shown over Trinity College by the Master, Dr Whewell, she was curious to know what all the pieces of paper floating down the river were, to which, with great presence of mind, he replied, ‘Those, ma’am, are notices that bathing is forbidden.’

George and Maud’s family formed part of the large and self- sufficient Cambridge clan of Darwins. Two of George’s four brothers Frank and Horace – had built family houses in the spacious meadows next to a house called The Grove, in Huntingdon Road, where their widowed mother and her unmarried daughter, Aunt Bessy, spent their winters. So Gwen and her brothers and sister grew up with a ready supply of entertaining and affectionate aunts, uncles and cousins, including Gwen’s special friend Frances, who would become known as a poet under her married name of Cornford.

Despite a considerable age difference and the fact that George, a Fellow of Trinity who had just been elected Plumian Professor of Astronomy, was quiet and intellectual while Maud was lively, sociable and instinctive, they seem to have complemented rather than irritated one another. ‘My mother’s calmness, good spirits and unshakable courage were very soothing to my father’s overstrung nerves,’ observes Gwen. ‘She was always kind and sympathetic to him when he was ill, and took his ailments perfectly seriously; but unlike a Darwin she did not positively enjoy his ill-health…and as a consequence he did get very much better.’

Though Maud was calm, this did not mean that she was organized. There is a delightful picture of her on the days when the cab with ‘red-faced old Ellis’ on the box drew up at the door to ferry her to Cambridge station for a day’s shopping in London, or even to the boat train for New York – still in her nightdress but perfectly composed, while her husband stood anxiously in the hall, watch in hand, and the three maids ran frantically up and down stairs fetching things. ‘Of course she had not attempted breakfast,’ writes Gwen, ‘and I used to put slices of buttered toast on the seat of the cab for her…When she was in the fly I used to hand in through the window her boots and button hook, so that she could put them on as she went; while she gave me in exchange her slippers to take back.’ (How that scene resonates with a family who are perpetually late and whose car frequently contains pieces of cast-off food and clothing.)

Every summer the extended family congregated at Down House in Kent, home of Gwen’s paternal grandmother, a Wedgwood by birth and widow of Charles, who had died in 1882, three years before Gwen was born. To Gwen it was paradise and perfection. Everything at Down was different and better than anywhere else — even the path in front of the veranda, which was made from large round shiny black pebbles taken from some beach.

‘I adored those pebbles I mean literally, adored; worshipped. This passion made me feel quite sick sometimes…This kind of feeling hits you in the stomach, and in the ends of your fingers, and it is probably the most important thing in life… In the long run it is the feeling that makes life worth living, the driving force behind the artist’s need to create.’

That is one of the wonderful things about Period Piece. Just when you are rattling along, enjoying some piece of social observation or human eccentricity, it stops you short with such a remark. In the chapter she calls ‘The Five Uncles’ — ‘among uncles I include my father. A father is only a specialized uncle anyhow’ — Gwen recalls that her grandfather once said he had never had to worry about any of his sons, ‘except about their health’. ‘Well that is not quite right. One ought to have to worry sometimes about young people, because they ought to be growing out in new ways,’ she writes, suggesting that, because Charles Darwin had been such a tolerant and broad- minded father, none of his children had ever had to rebel and had therefore, in some senses, never quite grown up. Gwen must have made a very sensible parent.

Humor, tenderness and affection are the keynotes of Period Piece, but there is a fierce and passionate undercurrent that tells you something about the artist Gwen became. As well as being a vivid picture of Cambridge academic society at the time, with all its rituals and hierarchies (perhaps in fact not so very different from today), it is, like all good autobiographies, an account of the making of a person which, even in a family distinguished for its ‘love of children and dogs’, can be a lonely process. Yet it was a recognition of that loneliness, of the need to guard something private and individual in her inner self, that must have helped Gwen to become an artist. Of the misery of boarding school she writes:

‘The chief thing I learnt at school was how to tell lies. Or rather, how to try to tell them; for, of course, I did it very badly… The truth was, that while I was desperately anxious to appear exactly like everyone else, yet at the same time, I intended at all costs to keep alive the precious little grain of me, which was inside. And no one can succeed in running with the hare and hunting with the hounds for very long.’