A few weeks ago, news broke that Paramount was planning to embark on a remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo with star Robert Downey Jr. You are forgiven if your reaction is one of deep skepticism. What can possibly be gained by remaking a film widely regarded as the apex of the art form? What director today can step into the shoes of the Master of Suspense? And who would ever mistake the star of Iron Man for Jimmy Stewart?

Gut reactions of this sort remind us of the scorn with which remakes in general are usually — sometimes unfairly — met.

After all, remakes are considered by all fair observers to be inherently synthetic and unoriginal, right? In remaking a movie, filmmakers plunder existing stories, characters and brands, usually with proven box-office appeal, in order to foist new — yet strangely familiar — versions on the public. As far as the skeptics are concerned, Hollywood imagines audiences’ memories to be so short, and their grasp of movie history so limited, that they will lap up multiple versions of the same film time and again, like Pavlov’s dogs munching on popcorn.

For this reason, many leading critics and tastemakers have long carped about the prevalence of remakes. In 1978, reviewing Philip Kaufman’s dazzling remake of the 1956 science-fiction classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers on their television show, critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert tempered their praise of that much-admired movie by bemoaning the whole godawful enterprise of remakes and their spiritual cousin in cinematic unoriginality, sequels. “Isn’t it amazing to you, as we see these films, that here’s this whole colony of filmmakers and they’re bereft of ideas?” Siskel said.

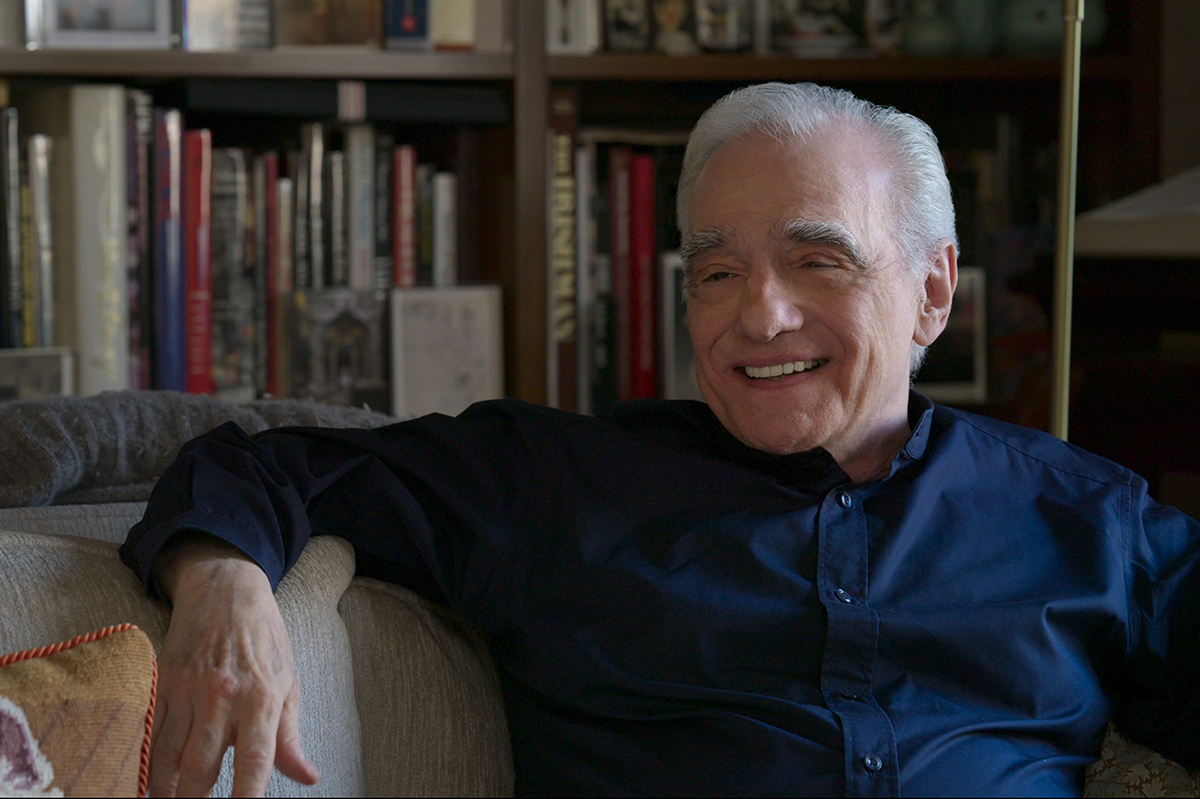

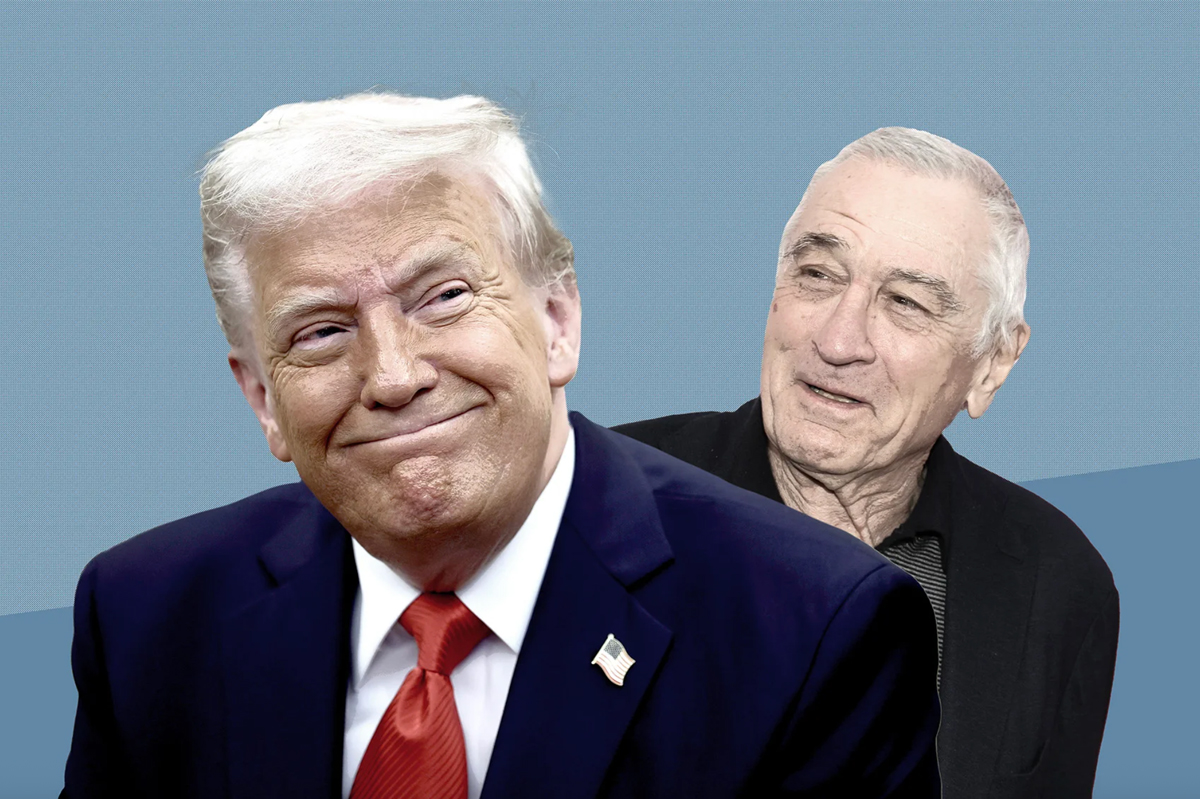

Hollywood didn’t listen. By the 1990s, remakes routinely attracted top filmmakers: Steven Soderbergh reimagined the classic film noir Criss Cross as The Underneath in 1995, Mike Nichols turned the French farce La Cage aux Folles into The Birdcage in 1996, and Sidney Lumet took a fresh crack at John Cassavetes’s crime drama Gloria in 1999. Even Martin Scorsese got in on the remake action: in 1991, just a year removed from directing the blazingly original mafia movie Goodfellas, Scorsese remade the 1962 thriller Cape Fear, casting Robert De Niro in what had been one of Robert Mitchum’s signature roles. New Yorker critic Pauline Kael did not approve of Scorsese joining the ranks of the remakers. “We’ve had nothing like Mean Streets or Taxi Driver for a long time now,” Kael said in 1994. “Instead we have the directors of those movies doing remakes of old films. I mean it was depressing that it was Scorsese remaking Cape Fear.”

Not only are films of genuine merit remade — 1937’s classic showbiz drama A Star Is Born begat no fewer than three remakes, including by Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga in 2018 — but those of far shoddier quality, too. Films as undistinguished as the lethargic disaster of The Poseidon Adventure and the notorious Goldie Hawn flop Overboard have been remade, though the quality of the originals is so low that one is tempted to call the new versions do-overs rather than remakes.

These days, the only thing more common than remakes is railing against remakes. But what if the skeptics have it all wrong?

Long ago, remakes had a definite raison d’être: in the era before home video and television, films vanished from sight following their initial theatrical runs. Consequently, the only way to bring a good story back to audiences was to tell it again. This practice seems to have been tolerated by most audiences, who sat for multiple versions, produced in fairly close succession of each other, of The Wizard of Oz, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and The Front Page, the last of which, after being made into a pretty good film by Lewis Milestone in 1931, was made into a masterpiece by Howard Hawks in 1940: His Girl Friday.

Back then, the idea was to use remakes as vessels to introduce a story to new audiences. “Two decades had passed: a lot of young people couldn’t have seen the first version, so I felt I should tell the story again — for them,” said Leo McCarey, explaining, in an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, his decision to remake his enchanting romance Love Affair (1939), starring Irene Dunne and Charles Boyer, as the even more potent An Affair to Remember (1957), starring Deborah Kerr and Cary Grant. Directors as respected and high-powered as Frank Capra, John Ford and William Wyler each remade their own films. So did Alfred Hitchcock, who, not particularly proud of his 1934 British-made, black-and-white The Man Who Knew Too Much, opted for color photography, new settings and Jimmy Stewart in his 1956 remake. “Let’s say the first version is the work of a talented amateur and the second was made by a professional,” Hitchcock told Francois Truffaut.

There’s another utilitarian case to be made for remakes: bringing films from faraway places to America. Hollywood has consistently used foreign-language films as fodder for remakes on the assumption that the original films were either spottily released or entirely unseen here. This practice has led to more than a few classics drawn from films made overseas, including John Sturges’s The Magnificent Seven (1960), based on Seven Samurai; Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot (1959), based on a German production, Fanfaren der Liebe; and, in something of a rebuke to Kael, Scorsese’s Oscar-winning The Departed (2006), a remake of the Hong Kong film Infernal Affairs. Before you make accusations of cultural appropriation, ask yourself whether a foreign film has a better chance of being rediscovered with or without the help of a remake.

Plus, since remakes come with already-established plots, themes and universes, filmmakers can worry less about world-building and focus more on riffing. A few years ago, when I interviewed Philip Kaufman about remaking Invasion of the Body Snatchers, he characterized remakes as being akin to a “variation on a theme.”

“I loved the original,” Kaufman said. “I saw it when it first came out. I’ve forgotten exactly how old I was at the time, but my friends and I were impressed by it. It’s scary; it works as a horror movie. What’s it about? Is it about McCarthyism? Is it about communism? What is the lurking threat?”

When the opportunity presented itself to remake the movie, which originally starred Kevin McCarthy and Dana Wynter, Kaufman hesitated at first — “I think my first response was, ‘No, I like the original,’” he said — before cottoning to the idea of updating it to contemporary times and relocating the setting from a small town to San Francisco. “For me, paranoia in America had really gravitated into the large cities at that point,” Kaufman said. “I thought, ‘Could we set that theme and do some variations on it, with contemporary actors, with going more for depth of character?’”

Kaufman’s film starred Donald Sutherland, Brooke Adams and Jeff Goldblum as urbanites facing the prospect of becoming “pods” — that is, invasive alien creatures who physically resemble people but are hollowed out of all human characteristics. Throughout the film, the cast is exercised by the question of who is a pod and who isn’t. “Could we explore more about what podiness, or being a pod, meant?” Kaufman remembered thinking. “How do you sort of put that against what being a human being means?”

Even during the making of the movie, though, Kaufman faced pushback: while shooting a scene in the Tenderloin neighborhood in San Francisco, the company encountered a street person observing the production. “There was a guy who was totally naked who was lying with his head on the curb, with arms behind his head, watching us rehearse,” Kaufman said. At one point, Kevin McCarthy showed up to do a cameo in the new movie, prompting the street critic to opine. “The guy says, ‘Hey, wait a minute, wait a minute — wasn’t you in the original?’” Kaufman recalled. “Kevin says, ‘Yeah.’ He says, ‘That was the better one.’ So before we even were halfway done with the movie, the first reviews were out.”

Nonetheless, good remakes, like Kaufman’s, preserve the infrastructure of their predecessors while adding fresh approaches that enhance the project. Thrillers or horror pictures, which are only as effective as the thrills or chills they induce, are particularly ripe for remakes. For example, in tackling Cape Fear, Scorsese seems to have recognized that contemporary audiences would demand more intensity, danger and even on-screen violence than the original — hence the difference between Mitchum’s understated menace and De Niro’s terrifying brutishness. Remakes can also take advantage of changing mores: Bob Rafelson’s 1981 remake of the film noir The Postman Always Rings Twice, starring Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange, told its story with sexual candor unthinkable in previous iterations of James M. Cain’s novel, including the entirely too polite 1946 film with Lana Turner.

The poorest remakes are those that are unable to slough off their predecessors. Gus Van Sant’s audacious 1998 remake of Psycho, which rigorously and inventively reproduced the visual scheme of Hitchcock’s 1960 masterpiece, ultimately fails to engage because the cast inadvertently reminds us of the iconic performances in the earlier film. (“Attending this new version,” wrote Ebert in his review of the Van Sant remake, “I felt oddly as if I were watching a provincial stock company doing the best it could without the Broadway cast.”) Perhaps no one has attempted a remake of, say, Casablanca or Breakfast at Tiffany’s because modern actors are rightly daunted by stepping into the shoes of Humphrey Bogart or Audrey Hepburn; anyone cast in those parts risks coming across like a Saturday Night Live impressionist.

So, with these pitfalls and opportunities, Robert Downey Jr. is tiptoeing into his remake of Vertigo. Perhaps he is doomed to fail; on the other hand, Kaufman — whose remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers was described, by Kael no less, as possibly “the best movie of its kind ever made” — once entertained remaking a Hitchcock movie himself: 1941’s Suspicion, starring Cary Grant and Joan Fontaine.

“We worked with a number of writers, including John Guare,” Kaufman told me. “That was a case where we felt there was more juice in that lemon that could be squeezed out.”

What juice is still in Vertigo remains to be seen — but let’s hold our fire in the meantime.