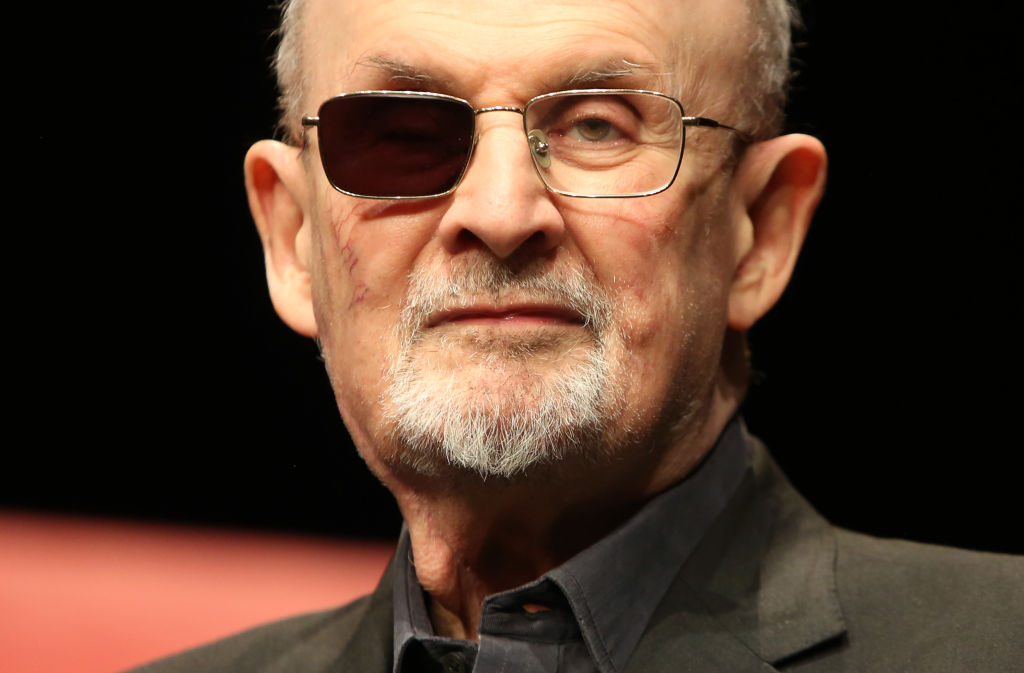

It’s hard to get your head around Salman Rushdie’s latest novel Quichotte, which has been shortlisted for the Booker. It’s a literary embarras de richesse, whose center can’t really hold, yet it’s written with the brilliant bravura of a writer who can really, really write. More to the point, it’s also funny and touching and sad and oddly vulnerable, rather like its eponymous hero.

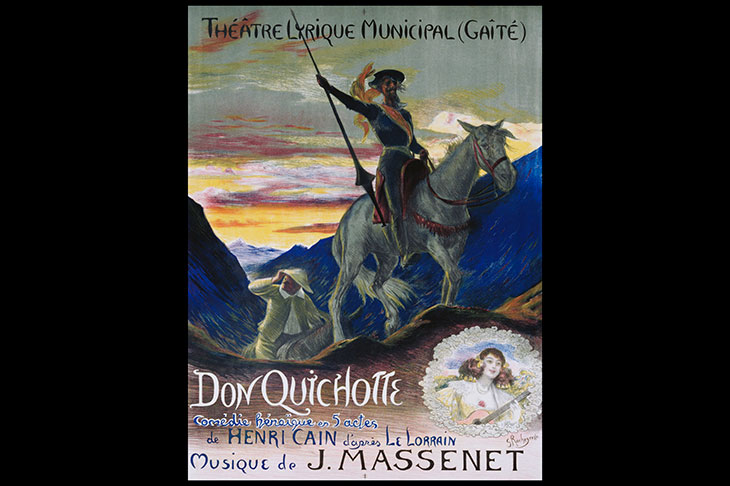

His name is taken from Cervantes’s Don Quixote, via its Frenchified version, courtesy of the composer Massenet (one cultural allusion at a time is never enough for Rushdie, whose references range from Prospero to Pinocchio, from Ionesco to Oprah, from Wordsworth to The Wizard of Oz). This Quichotte is an Indian-born immigrant to America, a small-time sales rep for a pharmaceutical company, aging and down-at-heel, who becomes as addicted to trash TV as Cervantes’s original was to the chivalric romances of his day.

Quichotte’s screen dream is a talk-show star, Salma R, a migrant from Bollywood to Hollywood. Convinced that he can save the world by winning her heart, he embarks, in somewhat Monty Python style, on a quest that takes him on a picaresque road trip across the United States. On the way he is accompanied by Sancho, the son he never had but has called into being by his yearning fantasies.

That, however, is only the start of the postmodern hall of mirrors in which we find ourselves. We soon discover that Quichotte is a fictional invention, created by a character from another, marginally less fictional world. It turns out that the tale of this quixotic quest is being written — even as we read — by a washed-up writer of unsuccessful spy thrillers living in New York, who has decided, as his last stand, to up his game in the high-culture stakes by turning to magical-realist literary fiction. Known only as ‘Brother’, he too is of Indian origin. The narrative segues between his story and that of his creation Quichotte, between which emerge numerous parallels.

In a post-truth environment, where even the president is ‘entirely fabulist’, the literary tradition of magical realism, with its roots in Cervantes, has a particular contemporary urgency that Rushdie exploits to the max. You can’t blame a creative writer for taking an omnium gatherum literary attitude in an ‘unreal real’ world that’s simultaneously globalizing and yet fragmenting.

So we’re hit between the eyes by a dizzying range of fictive positions and storylines from Kerouac to crime fiction to Armageddon sci-fi to Greek tragedy. There’s social commentary on the opioid crisis and financial corruption in Big Pharma (a subplot that would make a great Netflix series). Then there’s the collapse of the liberal consensus and the rise of crude populist racism. Plus, in a further twist, we get a billionaire scientist promising to rehouse his clients in space. En route, there are guns that talk and humans who turn into mastodons.

Yet the real value of this novel lies less in its flamboyant fantasias and literary tricks than in its poignant, almost excruciated delineation of human inadequacy and messiness — which stretches, Rushdie hints, as far as himself. Quichotte’s previous failed relationships are listed as including four women whose national backgrounds match those of Rushdie’s own ex-wives: ‘the Antipodean adventuress, the American liar, the English rose, the ruthless Asian beauty’. Rushdie may lack Quichotte’s chivalry, but he chooses to embrace the endearing naivety of his protagonist when it comes to humiliating self-exposure. Maybe this sort of human failure is all there really is of value.

As the novel unfolds, we are far less gripped by the transmogrified mastodons than by the human stories, told with Tolstoyan empathy. In the midst of all the dazzling sophistication, it’s the half-embarrassed psychological naturalism that counts.

Salma is a complex, deeply damaged, highly intelligent woman who was sexually abused in childhood, resulting in a need for fame matched by a drug addiction. Brother’s sister is equally compelling: a woman who left India for London under a cloud in her youth and made it into the British establishment against the odds, becoming a famous human rights lawyer, marrying a judge and having a daughter. We suffer with her as she sees her liberal value system begin to implode as she privately battles with terminal cancer. By the time Brother discovers her true history — she too was abused in childhood — it’s too late. Throughout all this novel’s permutations, family ties remain the only unquestioned, yet constantly threatened, source of meaning.

Towards the end, Brother offers his son, from whom he was formerly estranged, an artistic apologia for his magical-realist pursuits: ‘He tried to explain the picaresque tradition… how… through its metaphoric roguery it could seek to demonstrate and encompass the multiplicity of human life.’ The son shrugs, unconvinced. ‘Your son, the grand inquisitor,’ is the next line.

Rushdie is on record as saying how important it is for him personally to be a good father to his sons, Zafar and Milan (by different marriages). Like the lovable, deluded Quichotte in whom flamboyance and loserdom meet, he painfully exposes his insecurities in this novel. Not for nothing does he quote Saul Bellow’s deathbed pronouncement: ‘Was I a man, or was I a jerk?’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.