In May 1962, I was recuperating from a nasty broken leg — the result of a traffic accident in Paris — at my husband’s aunt Margot and uncle Brian’s enchanting cottage about an hour outside of London in Hertfordshire. The Dulantys’ cottage, called The Fisheries, was built in the 1820s in the village of Chorleywood, in a Constable-like setting on the bank of the River Chess.

I spent the first couple of days mostly on a sofa in the living room, overlooking the painterly scene, enhanced by Brian’s peacocks. The three pairs strutted around the property, displaying their gorgeous plumage and screeching as if they were the rightful owners.

But on the third day, boredom set in. The fairytale setting from my perch on the couch, along with the constant screeching of the peacocks, was challenging my sanity. Then Margot gave me a book she had received from Patricia Neal, a close friend who lived nearby in Great Missenden. Margot was godmother to Patricia’s daughter Olivia. Entitled James and the Giant Peach, the book was written by Patricia’s husband, Roald Dahl. “It’s a children’s book,” Margot told me, “and is causing quite a sensation. I couldn’t put it down.”

Nor could I, as I became completely engrossed in the wickedly funny tale of an orphaned boy with a huge imagination. The peacocks could screech all they wanted. And that day was the start of an enduring relationship. As the years went by, my three children loved Dahl’s nutty and complex tales as much as I did, as do my five grandchildren now.

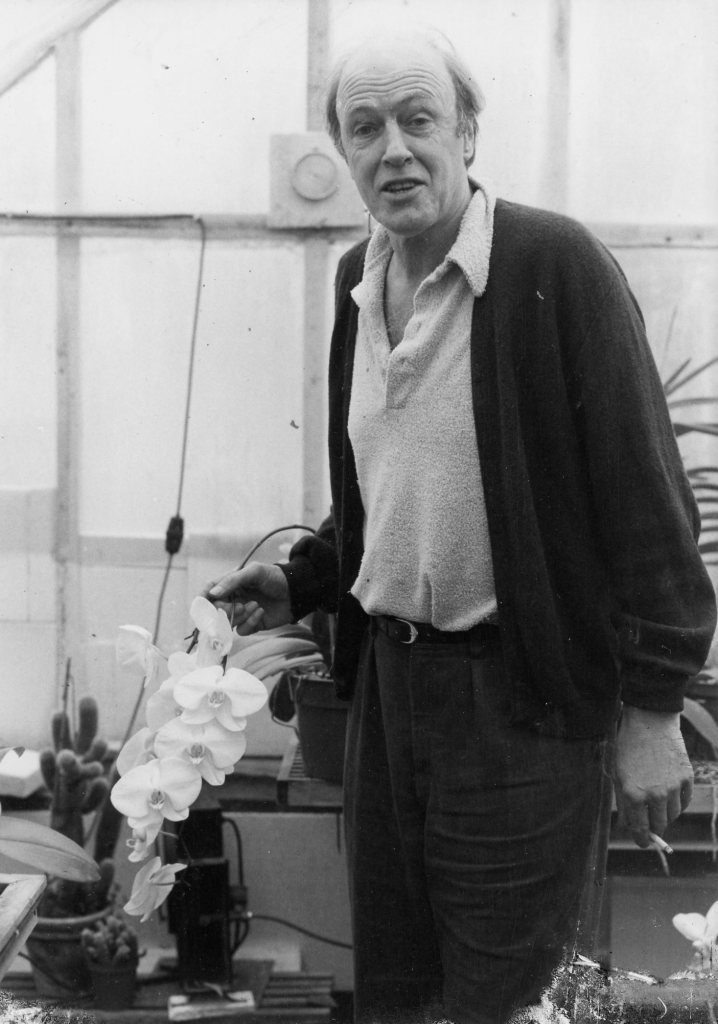

Today, though, Dahl seems to have found himself on the wrong side of history, with “sensitivity readers” editing his books to make them less likely to offend modern sensibilities. He was known to be an unpleasant man in many respects. But I want to show that there was another side to him, too. I may well be the last journalist alive who spent quality time with Dahl in his home, corresponded with him over some years and witnessed a side of him that many, except his family and friends, hadn’t seen.

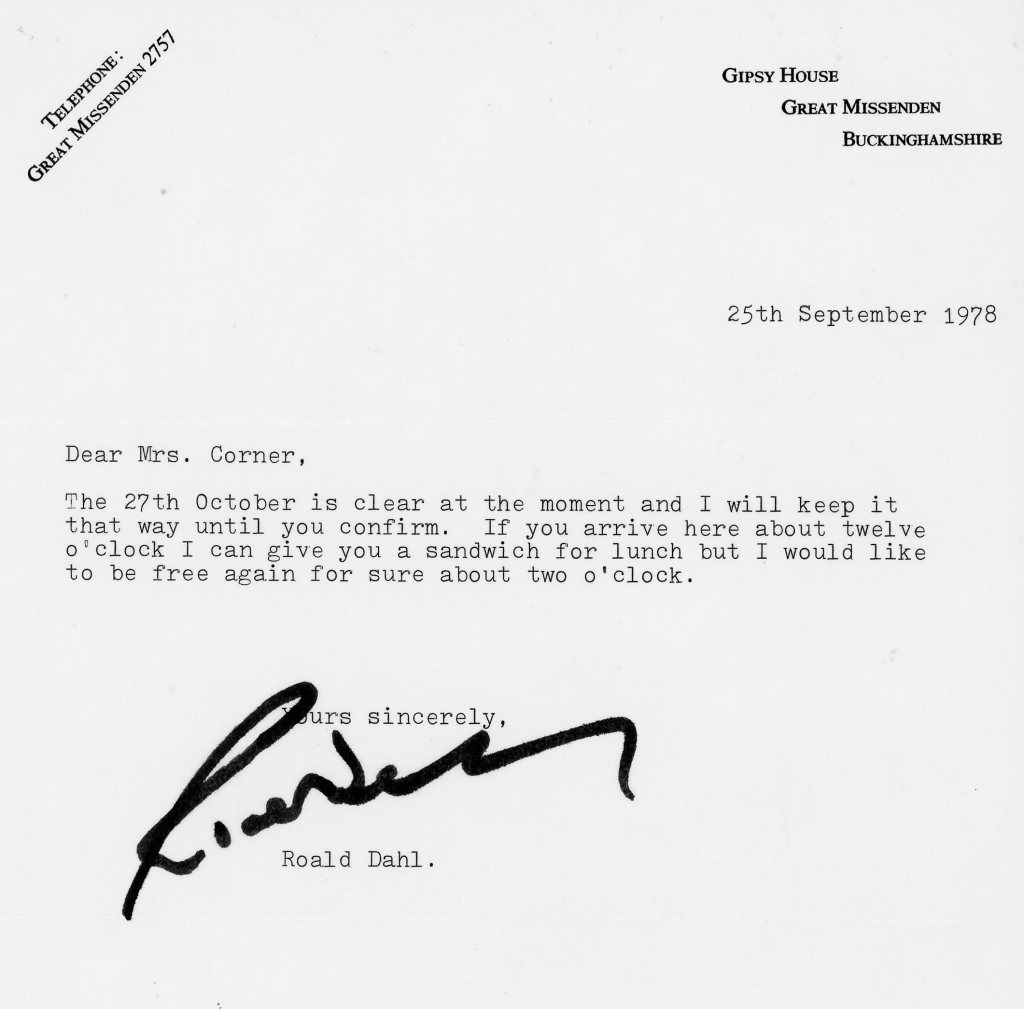

After discovering his brilliance that day on the sofa, I continued to follow Dahl’s work. When in 1978 he released a new book, The Enormous Crocodile, I took this as my lead to write and ask for an interview for the International Herald Tribune, for whom I was the Swiss features correspondent.

I had been wanting to interview Dahl for some time by then — not just the author, but also the inventor of a brain valve that saved his son’s life after a taxi crashed into his pram in Manhattan; the Dahl who played a major role in teaching his wife Patricia how to walk and talk again after her strokes; the decorated RAF pilot, shot down in the African desert during World War Two. And, of course, the man who made millions of all ages laugh. I loved his short, chilling, creative short story masterpieces that Alfred Hitchcock made into wildly acclaimed half-hour TV dramas.

Perhaps it was my brief mention that James and the Giant Peach had helped me through my convalescence at the Dulantys, or because I loved his children’s books as much as his adult stories, but a letter came from Dahl, saying that he would be available in October. He could only give me two hours and suggested we should pick a time that was convenient to both of us.

When October arrived I flew to London and took the train to Great Missenden, just five minutes from Dahl’s home, where he met me. Brian Dulanty had warned me that Dahl could be cantankerous, even rude, yet he immediately put me at ease.

“My wife is away in America at the moment,” he said as we pulled up to his sprawling farmhouse. “I only have peanut butter and jelly to offer you for lunch. I hope that will do. As you’re American, you’ve probably had a few of those!” I did not know at the time that he and Patricia were going their separate ways and would soon divorce. He would marry his long-time mistress, Felicity, with whom he would write a delightful cookbook, Memories with Food At Gipsy House.

As we entered the front door, I noticed a large, black sculpture in the yard. Dahl saw my interest. “That is by my friend and neighbor Henry Moore,’ he said. I wondered why Henry Moore (the Israel Museum in Jerusalem have many of his sculptures) and Dahl were such close friends since Dahl was an antisemite. “I’ll show you some of the paintings I’ve been collecting since I was a starving writer,” he added while spreading peanut butter and jelly on four slices of bread.

Taking our sandwiches with us, we went into the living room. The walls were covered with museum-quality paintings, many labeled with the names of important impressionists. Dahl told me the stories behind some of the most noteworthy paintings and asked me not to mention his collection as it wasn’t insured.

Dahl told me he didn’t like labels. He wouldn’t have liked me to say that his weird, macabre, outrageous, horrifying and often sick short stories and children’s books came from a host of personal experiences, although he wrote about war, gore, sex, art and perversion as if he had an inside lead.

He might have gone, however, for a term like irreverent. His wise face might even have cracked into a craggy smile. For Dahl was wonderfully irreverent. Nothing was sacred to him, or almost nothing; horsey women, male lushes, wine snobs, overindulgent parents, spoiled brats. He obviously loved children and said that his main reason for writing children’s books was to get kids away from TV. His jump into juvenile literature with James and the Giant Peach was an offshoot of his bedtime storytelling to his children.

Dahl was not so easy on adults. He didn’t care if he got hate mail, “just as long as they finish the book,” he said. He told me: “I don’t like non-fiction, my pleasure comes from inventing.”

He asked me if my children had been vaccinated against measles, and replied “Good” when I told him they had. His seven-year-old daughter Olivia had died of measles encephalitis in 1972, and he related how he had been sitting on her bed, showing her how to make little figures out of colored pipe cleaners, when he noticed that she couldn’t use her fingers. She lapsed into unconsciousness soon afterwards, and died twelve hours later.

In the end the two hours I’d been promised turned into five hours with Dahl, taking photos, meeting his then thirteen-year-old daughter Lucy, getting a “tour” of the gypsy caravan and the shed where he wrote, pencil in hand and pipe cleaners within reach.

I’d like to think that Dahl was enjoying my company and that was the reason he wasn’t “on the clock” with me. He signed a book to me. Finally, as dusk was approaching and the last train was about to leave that would enable me to catch the flight back to Geneva, Dahl drove me to the station.

I exchanged letters with Dahl for a few years. When his cookbook came out, I wrote to him about how lovely it was and how much my vegetarian daughter, Annabelle, liked Theo’s Peanut Roast.

Recently I’ve asked my children which of Dahl’s books and characters they remember best. Keith recalled The Hitchhiker, a tale about a pickpocket with fantastic, slim fingers. He remembered, when he was eleven, spending a lovely summer day with the Dahl family when he was visiting the Dulantys. “In spite of Dahl’s looming presence (Dahl was 6’6″), he was very kind to me, showing me the shed where he went to write and asking me about growing up in Switzerland. A BFG.” Annabelle recalled her fifth-grade class in Switzerland writing to Dahl and receiving a short story he’d written for the class about a cow eating the shed’s curtains. Lucy said she ordered many paperbacks of Dahl’s books when her children attended a French school in Antibes during Covid-19 to keep up their English.

My family isn’t alone in our love of Dahl. His books have sold more than 300 million copies and been translated into sixty-three languages. But as Ed Cumming at the Daily Telegraph revealed recently, Dahl’s books are now being edited by “sensitivity readers” who are inserting gender-neutral language and altering the descriptions of certain characters.

Off the page, Dahl has long been labeled a misogynist and racist. He admitted to being an antisemite before his death in 1990 at age seventy-nine. He didn’t apologize but his family issued this statement: “Those prejudiced remarks are incomprehensible to us and stand in marked contrast to the man we knew and to the values at the heart of Roald Dahl stories, which have positively impacted young people for generations”

There’s no doubt Dahl had many different sides to him, and not all of them were positive. But the time I spent with him suggested that not all of them were negative, either — and there’s a reason the popularity of his books has endured for generations.

This article was originally published on Spectator Life.