Each time an American institution commits a new corruption of the English language in the name of “social justice,” US wire services, assisted by the internet, circulate the latest absurdity to the four corners of the world. Nearly everyone I know has commented on the University of Southern California School of Social Work’s recent ban on the use of “the field” when referring to the world outside the classroom because it might have “connotations for descendants of slavery or immigrant workers that are not benign.”

In my circle of friends we laughed, a bit ruefully, and increasingly so do a few mainstream publications such as the Week, which headlined its item “Only in America.”

I tend to take these assaults on speech and writing more seriously than some of my colleagues, but I still have hope that the current tide of inanity and language abuse will inevitably ebb in the wake of this latest stupidity. Surely, I tell myself, ridicule from libertarian comedians like Dave Chappelle and Ricky Gervais, and eyerolling from national news editors, will win the day and halt the suffocating campaign to drive meaning, metaphor and colloquialism out of the language of Shakespeare.

But then came the news earlier this month that the Associated Press — the most important wire service in the world, the gold standard of old-fashioned journalistic propriety and plain writing — had itself perpetrated an act of violence against clear language and thinking.

The AP has long dictated style to the vast class of middle-brow American writers for whom H.W. Fowler is too highbrow and subtle. I grew up on the AP stylebook, and to this day cannot rid myself of certain of its rules about proper punctuation, such as serial commas.

So I was shocked when I read that the grand old agency had tweeted a new recommendation targeting what it claimed to be prejudice, but was in fact an attack on the very idea of generalization.

This recommendation urged us to avoid “general and often dehumanising ‘the’ labels such as the poor, the mentally ill, the French, the disabled, the college educated.”

I’m all for precision and a sense of proportion, but this was pretty idiotic — so much so that even the ultra-woke New York Times ran a gently mocking story that chided the AP, albeit cautiously: “The point it appeared to be laboring to make about facile stereotyping of large groups of people seemed lost in this instance.”

Nothing wrong with the intention, the paper’s Paris bureau chief, Roger Cohen, seemed to be saying, just with the execution, because the French government had taken umbrage at being sandwiched between “mentally ill” and “disabled.” Presumably, if “the French” had been left out, the AP’s faux pas wouldn’t have been so bad. In fact AP did apologize for having lumped the definitive article before the word “French” in its original tweet, heaping more absurdity upon absurdity.

It should be noted that the AP had already caved in to political fashion with its capitalizing of the “b” in “black” for references to African Americans, this in an apparent attempt at symbolic compensation or reparations for slavery.

I’m still not clear on why the “w” in white shouldn’t also then be capitalized, and no one, even the most woke of my friends, can explain it to me.

However, in the end, none of this is really funny, since language murder is causing collateral damage elsewhere. Because the woke war on language is merely one part of a wider war on truth.

It’s not just the people who have lost their jobs, unjustly, for repeating the wrong racial epithet at the wrong time. We’re also experiencing distortions of history, through phony language and art, that do insidious damage to the political culture.

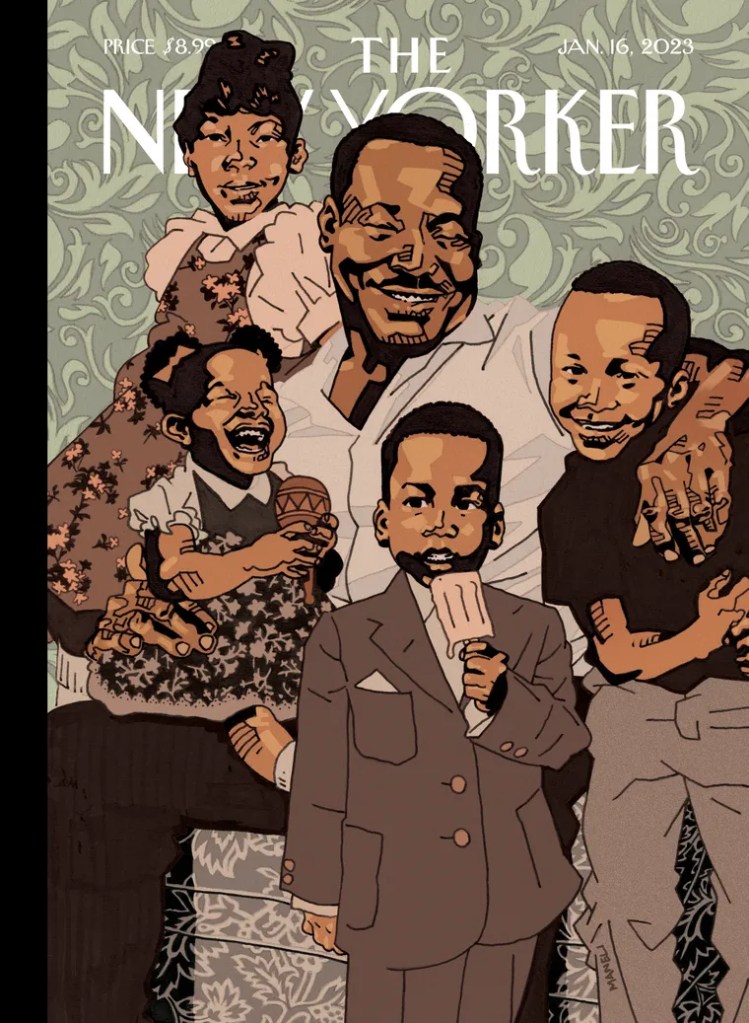

A prime example was the New Yorker’s January 16 cover, a sentimental painting of Martin Luther King Jr. and his four children titled “Family Man.”

King is one of my heroes — I can’t think of someone who mattered more in the politics and literature of my youth, or who better embodied the Christian doctrine of compassion and non-violence, than the civil rights leader who was assassinated at a Memphis motel when he was only thirty-nine. So I don’t need the artist Pola Maneli to help me, as the New Yorker described it, appreciate “King’s legacy and the difficulty in recognizing the humanity of our heroes.”

However, Maneli’s portrait was worse than just saccharine. It’s pretty well established — thanks to his biographer Taylor Branch and the vicious and unscrupulous FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who spied on King — that King was not a flawless family man.

At least one of his extramarital relationships seems to have been more than a passing fancy. Depicting him as a caricaturish “Father Knows Best” type utterly devoted to his children actually makes him less human, while it simultaneously depoliticizes him.

Maneli as much as admits it: “My first impulse was to try to depict him in an explicitly radical or assertive light as a response to how heavily sanitized his politics have become in the decades since his passing.” Evidently, the New Yorker talked him out of it.

‘While I definitely think that’s a valid impulse, as that part of his life should be highlighted more often, I quickly became uncomfortable with the thought of enlisting my work and his memory in a proxy battle with structural racism… The challenge of portraying as much of his humanity as possible really excited me, and I couldn’t imagine an environment where that would have been on display more than in his moments as a father.

What was King doing in Memphis on the day he died, April 4, 1968, at a moment when he wasn’t dandling his kids on his knee? He was scheduled to march with striking sanitation workers, very much in keeping with his move leftward toward the end of his life. His newly-formed Poor People’s Campaign was taking an increasingly prominent place in his political strategy and passion, alongside his campaign for equal rights for black Americans. But I guess that helping striking black people who pick up the garbage isn’t “human” enough to merit a New Yorker cover. Why bother to fight “a proxy battle with structural racism” when you can join the rest of the media and get paid to spread propaganda?

And there, I suspect, lies the central problem with the war on English. So many of the soldiers on the attacking side have no real interest in helping the oppressed people win. They’d rather just speak in tongues.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.