The State Department estimates that more than 3,000 Americans are imprisoned abroad, on grounds ranging from small amounts of marijuana to multiple murders. For all but a handful, the government explicitly states they cannot get you out of jail, tell a foreign court or government you’re innocent, provide legal advice or represent you in court. The president certainly is not in the habit of making calls to the Russians telling them to please let you go, you didn’t mean to have that vape cartridge of hash oil in your suitcase at Customs.

The key to getting the full force of the United States government working for your release is to be “wrongfully detained,” a qualification that applies to fewer than 40 out of those 3,000-some Americans locked up. The US recently declared Brittney Griner wrongly detained. What does all this mean?

Near the start of the Ukraine war, American WNBA star Brittney Griner was arrested trying to enter Russia carrying vape oil, which contained some sort of cannabis product illegal in Russia. This entangled her fate in the confrontation between Russia and the West. The Russian Federal Customs Service said its officials detained the player after finding vape cartridges in her luggage at Sheremetyevo airport near Moscow.

Normally Griner would be largely on her own. While the State Department visits Americans incarcerated abroad when that is possible (good luck if you’re popped in a country without a US diplomatic presence like Iran or North Korea, though the Swiss will often help out), the government will generally not get involved with innocence or guilt, and will not make representations to the host country to free someone. Most of us have seen Midnight Express.

In the case of Russia, the United States specifically warns,

do not travel to Russia due to the unprovoked and unjustified invasion of Ukraine by Russian military forces, the potential for harassment against U.S. citizens by Russian government security officials, the singling out of U.S. citizens in Russia by Russian government security officials including for detention, the arbitrary enforcement of local law, limited flights into and out of Russia, and the Embassy’s limited ability to assist U.S. citizens in Russia.

Worse yet, it looks like Griner did really have that illegal substance in her possession. She just pleaded guilty in front of a Russian court. In almost every such instance, she’d be on her own, but for one exception: the recent declaration by the United States that Griner is “wrongly detained.”

The wrongfully detained category grew out of a realization that a small percentage of Americans arrested abroad were indeed political prisoners, arrested abroad under a foreign country’s (unjust) laws, or were being held beyond the normal sentence or conditions for political reasons. In other words, hostages. If a person is declared “wrongfully detained,” the rules do an 180 and the full powers of the government are used to free you.

Congress in 2020 passed the “Robert Levinson Hostage Recovery and Hostage-Taking Accountability Act,” named after the American missing in Iran for over 15 years. The law establishes 11 criteria for a wrongful detention designation, any one of which can be a sufficient basis to secure the detainee’s release, including “credible information indicating innocence of the detained individual,” “credible reports the detention is a pretext for an illegitimate purpose,” “the individual is being detained solely or substantially to influence United States Government policy or to secure economic or political concessions from the United States Government,” or a simple conclusion that “diplomatic engagement is likely necessary.”

Secretary of State Antony Blinken must personally approve such a designation and transfer responsibility for the case from the State Department’s Bureau of Consular Affairs (disclosure: where I worked for 22 years) to the Office of the Special Envoy for Hostage Affairs.

What is next for Griner now that she has been declared wrongfully detained? Depending on the political goals of the Russians, her guilty plea may suffice. A Russian court will impose a fine or jail sentence to be waived, and Griner can be on her way home. But this is most common when the American has harmed a host country national and some public “justice” needs to be seen being done. A similar outcome often arises out of humanitarian needs, where Griner would be declared in need of medical care not available in Russia and sent home in an act of good will.

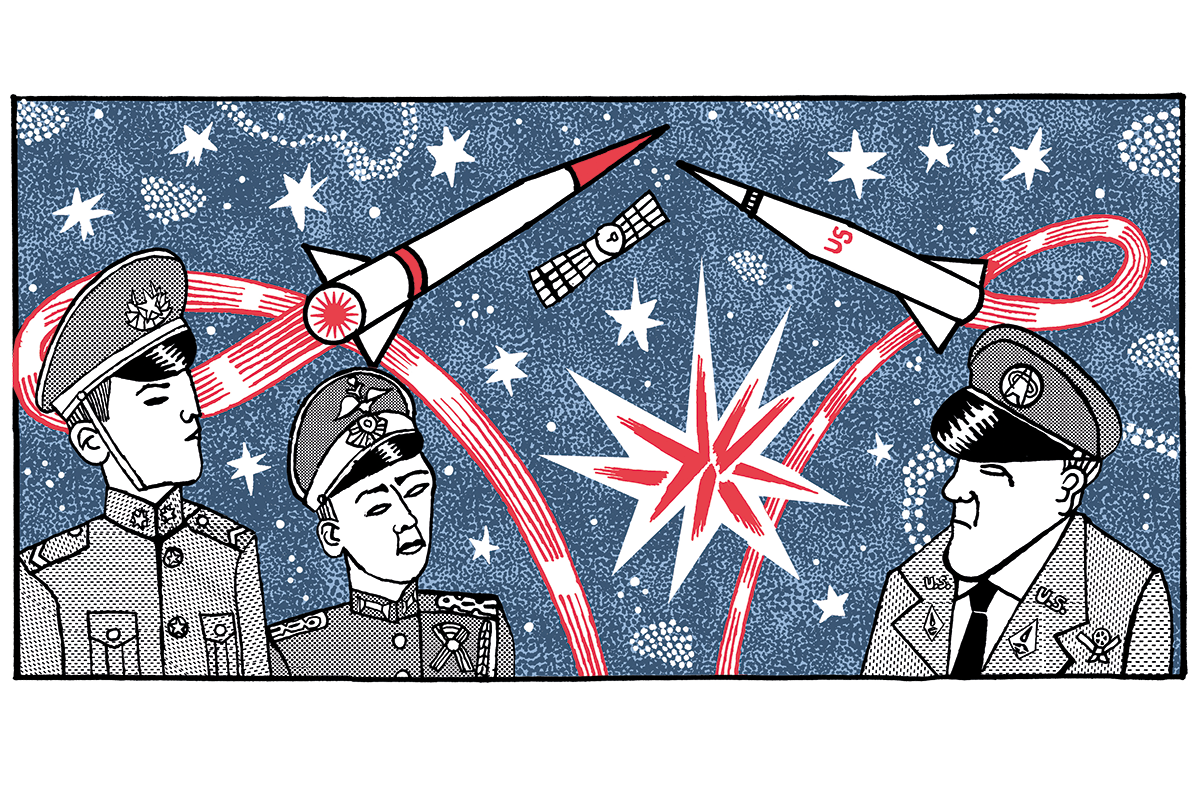

But given the politics of Griner’s arrest, a very likely outcome will be a prisoner exchange. The Russians are interested in the release of Viktor Bout, sentenced to 25 years in an American prison for trying to sell weapons to Colombian terrorists. This would track with diplomacy just this April that led to the exchange of Trevor Reed, a former Marine who had been held for more than two years over a bar fight, and Konstantin Yaroshenko, a Russian pilot serving a 20-year federal prison sentence for drug smuggling. Reed’s health was cited as the motivator for the swap.

One problem stands in the way of Griner’s release: it would be politically difficult for the US to again leave behind Paul Whelan, another former Marine, arrested in 2018 on espionage charges and sentenced to 16 years in prison, for Griner. Meanwhile, Russian media outlets claim talks of a possible prisoner exchange are already underway.