On February 14, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued an edict granting himself emergency powers to rule Canada by martial law with the intent of making all those trucks back up. He wants to confiscate them along with freezing truckers’ bank accounts. His soldiery is not altogether with him. Ottawa’s chief of police, Peter Sloly, abruptly resigned. Things aren’t looking bright for North America’s newest autocracy. But, OK. Let’s back up.

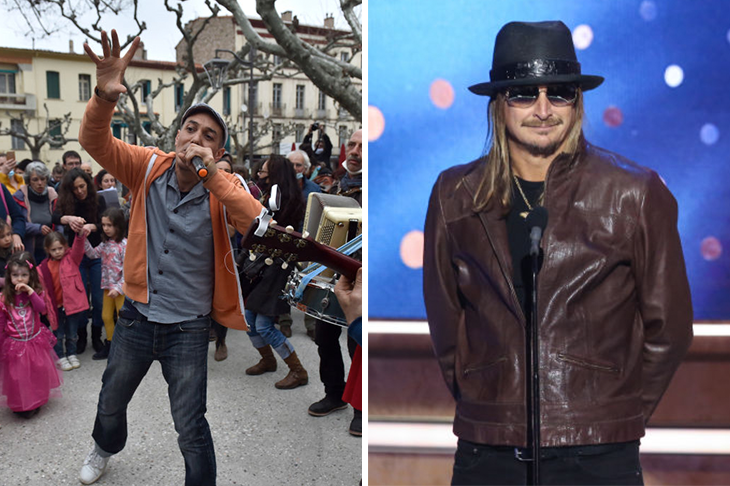

On December 18, 2020 a French musician known as HK (Kaddour Hadadi) and his group the Saltimbanks released on video a song titled “Danser encore” (“Dancing Again”). Within days it was a popular hit and within the next few months it became “le hymne du déconfinement,” a mass phenomenon in France, before spreading to the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland and beyond. Flash mobs assembled in train stations and other public places to sing the jaunty if slightly melancholy song and to dance to it. It became the soundtrack to Covid shutdown’s first mass protest against government restrictions on people getting together. Crowds of joyful, mostly maskless people performed the anthem declaring their freedom — or at least their longing for freedom. The refrain is:

Nous on veut continuer à danser encore

Voir nos pensées enlacer nos corps

Passer nos vies sur une grille d’accords

(We want to keep on dancing

See our thoughts embrace our bodies

Spend our lives in search of harmony)

“Grille d’accords” means “chord chart,” but harmony is more agreeable in English.

Hadadi explained to a journalist that he wrote the song the night after France declared its second shutdown in which artists, musicians and many other workers were declared “nonessential people.” That stung. Hadadi said, “I was rehearsing a show in a residence in Avignon with friends and, in fact, our show was canceled because we were not considered essential.”

He told another reporter, “We, the artists, we were part of it. We took that both as an insult but also as a frustration at not being able to do our job, which is also our passion and which is also our role in society… and during this epidemic.”

Hadadi, who is the son of an immigrant fruit-and-vegetable seller, had channeled the mood of a huge segment of the European public. The “protest” for which “Danser encore” provided the music was more joyful than angry, but the underlying resentment against the authorities was clear. What followed was an outburst of YouTube videos from both artists and ordinary people, nearly worldwide. It did not, however, make much of a dent in the US. Then came compilations of the most colorful (and the most mournful) performances.

First came the singing and dancing, then came the trucks — and then came the Canadian prime minister. Of course, protests against governments that have stepped on basic liberties in the name of fighting Covid have been happening all along, but in the year between “Danser encore“ and the Canadian truckers’ convoys nothing has achieved such a level of mass appeal. It is worth comparing the two.

The place to start is the street. These are protests that vibrantly assert our interconnectedness and are aptly staged on roadways and other sites where people are normally in motion. For “Danser encore” that included train stations and sidewalks; for the truckers, it includes highways, bridges and border crossings. Part of what they have in common is that public roads became a stage for movement that defied authoritarian control. The truckers in their slow-motion convoys across a continent were performing a dance of sorts. Both dancers and truckers were acting out a freedom that they saw slipping away under the new rules. Both were protests aimed at preserving freedom, rather than demanding new rights.

Hadadi’s song was written as a protest against government infringement on the freedom of artists to perform. Musical protest against Covid-authoritarianism didn’t begin or end with “Danser encore.” The group Fred209 had previously released Merde Mon Maske, (Shit, my mask!) a jokey song about a man who forgets to wear his mask at a bakery, but which began to articulate the underlying resentment of the new rules. Hadadi and the Saltimbanks followed up “Danser encore” with another street dancing anthem, “Dis-leur que l’on s’aime, dis-leur que l’on sème,” (“Tell them we love each other, tell them we are sowing”) which explains, “Tell them we are free / At each dance step in public.” The sequel, which opens with a mournful violin solo, in contrast to the bluesy saxophone that opened Hadadi’s original “Danser encore,” signals a darkening mood, even though the lyrics sound confident. Dancing may be a temporary reprieve from state-imposed isolation and fear, but the dance ends and the repression continues.

More recently Kid Rock released his single “We the People,” which is a no-holds-barred denunciation of the Covid regime. It opens:

We the people in all we do

Reserve the right to scream “Fuck you”

(Hey-yeah) Ow

(Hey-yeah) Huh

“Wear your mask, take your pills”

Now a whole generation’s mentally ill

(Hey-yeah) Man, fuck Fauci

This is a long way from “Danser encore,” described by one observer as “elegant but unafraid to be provocative, perfect for a ballroom scene in a film, traditional in style, is political without being too pushy about it.” The “Danser encore” counterpart to Kid Rock is:

And when in the evening on TV

The good king has spoken

Come to announce the sentence

We show irreverence

But always with elegance

We’ve moved from HK’s wistfulness to Kid Rock’s vitriol. The truckers are somewhere in between.

They are angry at vaccines mandates, vaccine passports, but mostly at government highhandedness. The behavior of the police in Ottawa, where people have been hauled off to jail for honking their horns in support of the protest — and the authorities have been confiscating gasoline cans used to refuel the idled trucks has brought opprobrium to the Trudeau government. Safe to say that no one, on either side, now feels like dancing.

Behind the political division over the truckers’ protest lie the deeper divisions over the purposes of law and self-ownership. The cultural divide between the elites and ordinary people on these matters is anything but simple. The Covid authoritarians tell us the mandates are necessary for public safety, but at the same time refuse to address the evidence of the possibly harmful and occasionally deadly effects of the vaccines — and insist on administering them to children who are at virtually no risk of the disease. Likewise, the mask mandates appear merely theatrical. There is no solid evidence that they impede the transmission of the virus, though they plainly impose significant psychological costs. Social distancing rules and shutdowns of commerce similarly have faint if any justification in “public safety.”

An elite that bases its legitimacy on superior knowledge and expertise would seem to be in an oddly self-discrediting position in setting forth rules that transparently don’t work. We have, for example, the recent working paper published by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise, “A Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of The Effects of Lockdowns on Covid-19 Mortality,” which presents a strong case that the lockdowns had no effect on the number of people who died in the epidemic. In the name of “medical safety” we have a regime that imposes marginally tested vaccines and manifestly destructive social rules. Is it any wonder that people rebel? The only real questions involve how this rebellion will shape itself. HK or Kid Rock? Defiant state governors or blockaded bridges? Passive disobedience or organized attacks?

One view of law is that it is a tool to get people to conform. It is a way of imposing rules that may help to stave off catastrophes such as global warming or to bring about a new social order deemed superior, e.g. socialism. This is Trudeau’s position. A different view of law is that it protects against unjust actions by those who hold power. It is a way of guaranteeing our natural freedoms against those who would infringe on them. The truckers have been eloquent in saying this in words as well as deeds.

These views are in stark opposition, yet there is truth in both. Society does need some kinds of conformity. Traffic signals work only if we conform to the idea that red lights mean stop. Subway turnstiles mean you need to pay a fare. And at a more profound level, society continues to flourish only if we have some baseline conformity on the right ways to bring children into the world, and to care for and educate them.

Those who protest either by dancing in the streets or diesel-truck blockading them are not seeking freedom from such civilizing order. To the contrary, they seek its restoration and they favor the kind of collectivism that underlies that order. When Covid authoritarians negate parental power over children’s vaccinations and masking, they are abusing their powers in a manner very similar to the abuses they display in imposing DEI curricula, gender-neutral school restrooms and transgenderism. The issues are not all one and the same but they connect. People may agree on one, disagree on another, yet share the intuition that all these public disputes come down to the question, “Who rules?”

When Hadadi composed “Danser encore,” he captured the psychological assault that was at the very center of Covidocacy:

Chaque mesure autoritaire

Chaque relent sécuritaire

Voit s’envoler notre confiance

(Every measure of authority

Every whiff of security

Sees our confidence vanish)

The song ends with Hadadi calling for “resistance” to “the instruments of their insanity.” In Ottawa right now that resistance is taking the form of thousands of additional Canadian flag-waving protesters. They are not all behaving with the immaculate politeness for which Canadians are famous, but they are far from Kid Rock-style rambunctiousness and they are definitely not the fascist thugs that Prime Minister Trudeau has labeled them. They are simply people in the midst of reclaiming their sense of identity as free citizens. They have declared that they will ignore Trudeau’s “emergency” steps to remove them.

One thing about a song. When it ends, people can sing it again.