In December 1921, a twenty-two-year-old Ernest Hemingway, then the European correspondent for the Toronto Star, came across the oddest group of immigrants in history — the White Russians who had fled the Bolshevik Revolution.

“Paris is full of Russians,” Hemingway told his readers. “They are drifting along in Paris in a childish sort of hopefulness that things will somehow be all right, which is quite charming when you first encounter it and rather maddening after a few months. No one knows just how they live, except by selling off jewels and gold ornaments and family heirlooms that they brought with them to France.”

Hemingway neatly summarized the meat of this gripping latest book by Helen Rappaport, the author of The Romanov Sisters and Caught in the Revolution. By 1926, 35,000 émigré Russians were living in Paris. Never had there been such a professional group of exiles, comprising doctors, dentists, lawyers and university lecturers. The problem was they were forbidden to practice their chosen professions in France, thanks to employment regulations and the requirement of French nationality. The most popular job for the now-fallen Russian ex-professionals was taxi-driving.

Some of them got around this by working exclusively for the Russian population. The former Russian ambassador to France, Vasily Maklakov, ran the Russian Emigration Office and set up a legal service for émigrés. But even he was subject to the great, poignant tragedy of this book — the precipitate fall from grace, from the giddy heights of running imperial Russia to becoming the servant class in Paris.

The most moving— and famous — examples are of Russian aristocrats and the former royal family. Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia (1890-1958) was born in St Petersburg, the granddaughter of Czar Alexander II and first cousin of the last czar, Nicholas II. She was also a first cousin of the late Prince Philip — a reminder of how close the long-distant past can be. By the time she got to Paris in 1920, she had to become a seamstress. In her younger days, she recalled, she and Empress Alexandra “used to amuse ourselves by making dresses for the little Grand Duchesses” — the Romanov sisters Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia, later so cruelly murdered.

In reduced circumstances after the Revolution, Maria took to knitting American-style sweaters to commission, copying designer dresses and making lingerie for Russian friends. She initially did it all by hand — she didn’t have a sewing machine. But she clearly had a strong work ethic, despite her blue-blooded youth. In Paris, she got hold of a Singer sewing machine and a cutting table, and improved her fortunes by making clothes for her fellow Russian exiles. She even set up her own clothes design business, Kitmir. Twenty-seven Parisian fashion houses were set up by Russian émigrés between 1922 and 1935.

But even Maria was subject, like all her fellow exiles, to desperate nostalgia. “All our conversations still turned around one subject,” she recalled — the past.

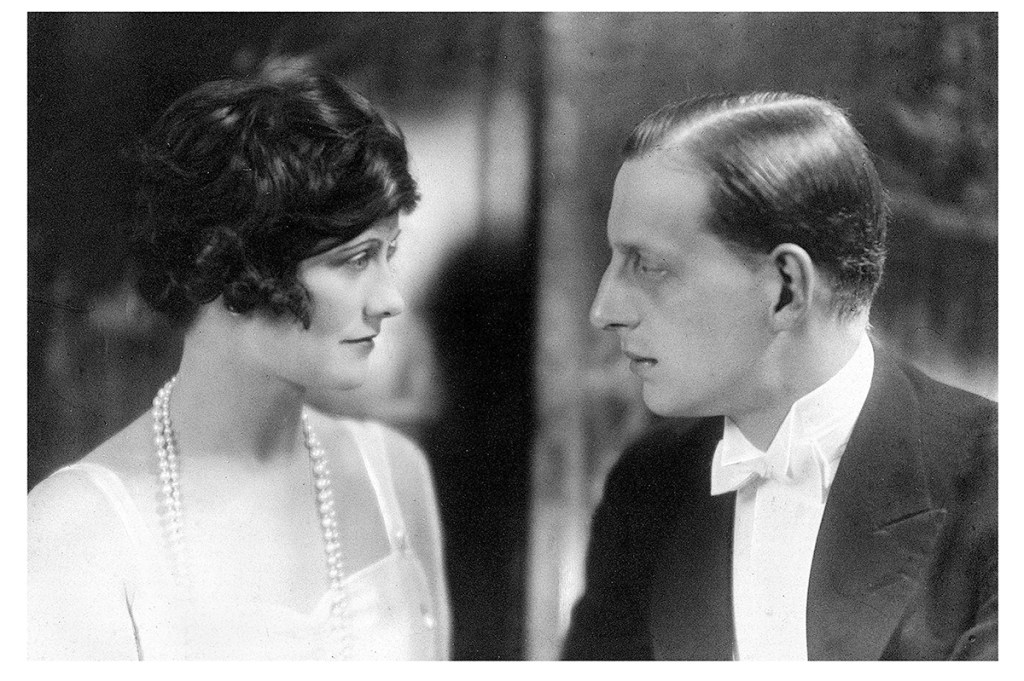

Melancholy and alcoholism are strong streaks in the Russian character. Both characteristics were deepened by exile. Her brother, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, suffered even more from the acute agony of nostalgia — a term that literally means “the pain of return.”

Dmitri was dubbed “a Romanov Hamlet.” He was tormented by the past, the early death of his mother and the murder of so many of his relations in the Revolution. The initial relief of escaping death was eclipsed by the catastrophic change in his fortunes. He had been the fourth richest man in Russia before the Revolution. When he got to Paris in 1918, he had “less than a hundred francs [eight dollars] in his Grand Ducal pockets, and only one extra shirt.”

You could say that this was a First World problem. How many refugees today arrive on foreign shores with absolutely nothing — and with none of the contacts a Russian aristocrat had? But Dmitri and most of his contemporaries were in fact hobbled by their earlier privilege. At twenty-seven, he had nothing other than his good looks and blue blood to get by on. As the Grand Duke himself said, “How did all my class live? We knew nothing — that is, how to do nothing.”

His lover, the designer Coco Chanel, said he shared a quality with all the dispossessed Russian grand dukes: they were “diminished — almost emasculated by their poverty in exile… They looked marvelous, but there was nothing behind… They drank so as not to be afraid. They were tall and handsome and splendid, but behind it all — nothing: just vodka and the void.”

“Vodka and the void” would have been rather a good alternative title for this engagingly sad book. Rappaport doesn’t confine her study to aristocrats. She writes of an eighty-strong company of former Cossacks from the same regiment. They all worked as porters and freight-handlers at the Gare de l’Est. Several of the officers refused work elsewhere “rather than break up the unit.” They all slept in the same wooden barracks, decorated with photographs, arms, uniforms and a regimental flag.

Whatever their background, the White Russians were bound together by it forever. The aristocrats had been born into well-connected comfort. The soldiers had enjoyed a professional esprit de corps in Russia. In their new, diminished life in Paris, they couldn’t hope to break apart and find similar connections among the French. Thus, they stuck together for life. That rule applied even to the White Russian garbage collectors of Cannes, renowned for being “very elegant and glamorous in their military tunics.”

In Down and Out in Paris and London, George Orwell captured the White Russian fallen on hard times in his fellow plongeur, Boris: “All the clothes he now had left were one suit, with one shirt, collar and tie, a pair of shoes almost worn out, and a pair of socks — all holes.” And yet, through it all, Boris continued to dream of a change in fortune and of “wearing a tailcoat once more.”

That solidarity and haunting affection for the mother country and a gilded past clung to the exiles until their deaths — in many cases, long after the Second World War. Their children, born in Paris, gradually lost those Russian connections but also, thankfully, cast off the nostalgia and the melancholy. Rappaport paints a strikingly similar picture of the desperate White Russian exiles who fled Odessa for Istanbul after the Russian Revolution. In Istanbul, the same pattern quickly emerged: generals working in laundries, princesses standing on the Galata Bridge selling blouses, uniforms and bunches of violets. The unluckiest ones became prostitutes.

In a clever touch, Rappaport shows how those same aristocratic types had lived high on the hog in the French capital just a few years earlier, on the eve of the First World War. At Maxim’s one evening, a grand duke presented his mistress — one of Paris’s grandes cocottes — “with a 20-million franc necklace of pearls tastefully served on a platter of oysters.” She touches, too, on the brilliance of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris just before the war, when Russian art, creativity and originality were at their height. When asked how difficult it was to pull off his grands assemblés — gravity-defying extended leaps — their star Nijinsky replied, “No! No! Not difficult. You have just to go up and then pause a little up there.”

Not the least of the idiotic horrors of the Russian Revolution was that it led to the departure of some of Russia’s most talented figures — just as Nazi Germany later murdered and exiled some of its greatest minds in its crazed hatred of Judaism. Rappaport gives a list of those who arrived from Russia in Istanbul: governors, prosecutors, nobility, hussars, dragoons, Cossacks, newspaper editors, reporters, photographers, singers, artists, musicians, doctors, engineers, agronomists and schoolteachers.

How mad and nasty of the revolutionaries to drive anyone out, but particularly those who formed the backbone of the country’s administrative, intellectual and artistic heart. And how eternally sad for those exiles. As the poet Anna Akhmatova, who didn’t manage to escape, wrote, “I forever pity the exile/ A prisoner, an invalid.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.