Pity the aesthete, the flâneur and the opera-goer. Those who find the contents of their own heads so dull and mundane they must fill them instead with the fantastical inventions of our most extravagant lunatics. They have been locked out of the theaters and cinemas and public spaces that make them feel at their most alive and abandoned to the content programming of Netflix and whatever Tenet was supposed to be. They’ve been deprived, sheltered, cut off from the only thing that gives their lives meaning.

I’m describing me. I’m asking you to feel sorry for me. If I don’t, at least twice a week, have a reason to wear a ridiculous gown and watch people leaping about on a stage set to a glass-shattering score, I feel only half alive, and I have been languishing under lockdown.

There has been some experimentation with bringing the art world into everybody’s living room, but a poorly filmed opera, with the cameras right up close where we can see the pancake make-up and thick eyeliner on the tenors, watched on the same couch I slouch on to watch the Copa America matches, doesn’t really recreate the transcendent experience of the theater.

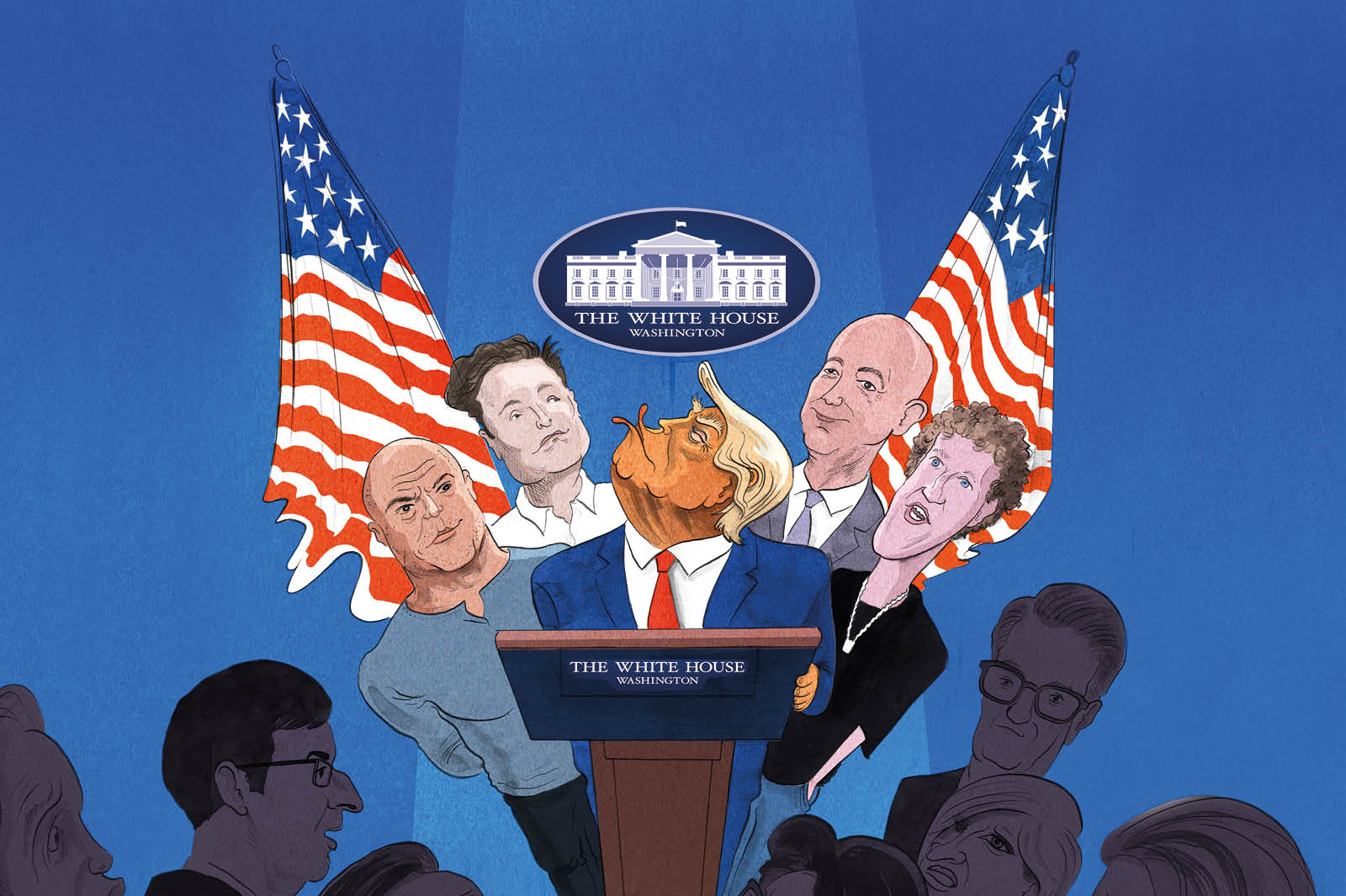

So I was a little trepidatious about how this adaptation of Wallace Shawn’s hit play The Designated Mourner into a podcast was going to work. But it works extremely well, and it is a joy to listen to. Well, ‘joy’ is overdoing it, as its story of ongoing political collapse and the rise of an oligarchic class is maybe just a smidge too much like watching the news these days, but it does take what can be the most powerful elements of a stage production and find a way to reproduce them in a more intimate setting.

The 1996 work is transformed into something halfway between a radio play and podcast, light on the Foley artist side of things, putting an emphasis on the intense monologues that feel akin to the usual bro-y discussions you get in most podcasts these days, where digressions and anecdotes litter the more serious conversations about whether or not we are living through the apocalypse. Shawn revives his role as Jack, the professor who is obsessed with his grief and disappointment as society falls apart around him.

It’s a work that has survived through many different forms and adaptations, finding new life in multiple stagings, film and now a podcast. It retains its aggressive and confrontational power, and it’s easy to forget you are listening to a work of fiction. Which probably doesn’t say great things about our political reality, but that’s fine.

It’s an interesting question, why we need certain works of art at certain times, and why films, plays and novels can lurk, waiting for the right cultural context to be ‘rediscovered’ and resonate in a whole new way. There’s a new podcast from Mubi that investigates this phenomenon. Mubi started as a film-dude streaming site, relying heavily on promoting work from the festival circuit that couldn’t find wide distribution because it wasn’t very good. Lately, though, it has flourished in a world where, if a film’s characters aren’t decked out in Spandex and capes, people aren’t interested, and they have met the moment by curating films that can’t find wide distribution for that other reason things tend to flop: because they are actually good. They are now a reliable source of surprising and innovative films from both neglected geniuses of the past and fresh international voices.

With their wide knowledge of cinema past, present and future, they have launched a new series called, rather predictably, the Mubi Podcast, investigating what conditions are required to make a movie a sensation. They interview critics, filmmakers, actors and viewers of the films that had an overwhelming response, focusing on unpredictable choices such as Paul Verhoeven’s Turkish Delight, a small independent that became one of the highest grossing Dutch films of all times, or the Mexican romance Yesenia, which became an enormous hit in the 1970s Soviet Union.

It’s unexpectedly good. If you’ve spent any time with other film podcasts, you know it’s usually just a bunch of dudes in a room spouting their very important opinions. It’s refreshing to hear a series where serious attention is given to how collaboration happens, why specific stories become necessary, and how difficult it is to recreate the conditions of runaway success. My only worry is that the series is so good it’ll be forced to continue until they have to explain why America became so enraptured by superhero movies, to the detriment of all other stories. If I am to be pitied, it doesn’t even compare to the hopes and prayers we must direct to the lad assigned that burden.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.