Had I been on the pier just a few days earlier, strolling past the penny arcades, I would have heard the distinctive whompf of Russian artillery fire. Ukrainian politicians are keen to turn the city of Mariupol (population 440,000) into a resort akin to those in Crimea and Turkey. Yet despite the pleasant climate, it feels more like Port Talbot than a subtropical vacation spot. The vast industrial limbs of the city’s deep water port, built by Czar Alexander III in the 1880s, crawl across the horizon. By the time the Azov Sea reaches the town, its clear blue waters have been tinged a muddy brown.

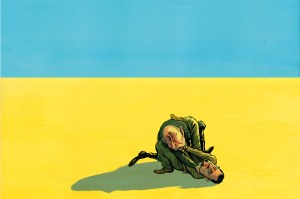

Ukraine’s most recent casualties came during the sudden build-up of Russian troops just a few miles away. One of their number, a member of the marine corps, was killed by a sniper: the headshot tore apart his helmet, now held at his regimental barracks as a memorial. The cleaned up relic sits next to spent ammunition casings and funeral service sheets — hung above the shrine are photographs of all the fallen marines. But these are only the men who died in this battalion.

For the full display of the Ukrainian fallen, one must visit the capital and look upon the thousands of names on the Wall of Remembrance at St Michael’s Monastery, Kiev. The crowning memorial is a metal statue of a Ukrainian soldier, complete with celestial wings. His helmet, however, is real; as is the iron angel’s rifle. Both belonged to a marine killed several years ago.

The few Ukrainian vacationers who do decide to risk a trip to Mariupol will quickly find their vehicles pulled over. Cool boxes will be searched and beach towels unfurled by surly troops brandishing Soviet Kalashnikovs — older, probably, than the souls they’re strapped to. Without surrendering to an inspection, nobody enters, and nobody leaves. The town is nothing like the western cities of Lviv and Kiev, which resemble Paris or Milan far more than anywhere from the former USSR.

Between checkpoints lie freshly dug trenches, tied together with razor wire and dotted with wooden pillboxes. These emplacements now house the same shifty young men that shake down the few visitors, built from the pines that are common all over Ukraine. It is a world of dirt and gun grease — soon, many expect, the smell of blood and cordite will be added to the mix.

Once inside the perimeter, the besieged city feels much like any other eastern European town: young entrepreneurs type away in café workspaces, groups of laughing teenagers sit beside them chatting over coffee. In the street, conveys of military trucks trundle past, mostly ignored.

There is a sense of carefree tension — the sort of paradoxical emotions Londoners felt during the Nazi bombings. Since fighting broke out in 2014, the area has come under repeated attack, but every attempt to break the Ukrainian lines has stalled. Mariupol sits between the annexed Crimea and Russia’s Potemkin republics in the Donbas. The city is a testament to the Kremlin’s military failure, which is precisely why the authorities are worried.

Now the town’s drinkers stay out later. Many gather in the central park, an area that by night is bathed in the glow of multicolored lights that illuminate fountains and water features. Late night strollers are almost all young and many are couples; vodka and beer seem to be the drinks of choice.

Mariupol’s soldiers, meanwhile, are waiting for another Russian assault. The commander of the Ukrainian marine corps 503rd battalion, colonel Vadym Sukharevsky, explained that his men are used to close whites-of-their-eyes combat, sometimes as close as 65 yards. ‘In 2017, we even engaged in hand-to-hand fighting,’ he says.

The Donetsk Oblast has been a battlefield for nearly a decade. Much now hinges on Biden’s plan for Putin. But the marines retain their resigned optimism. ‘We are ready,’ one of them says, smiling. ‘We are always ready.’

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.