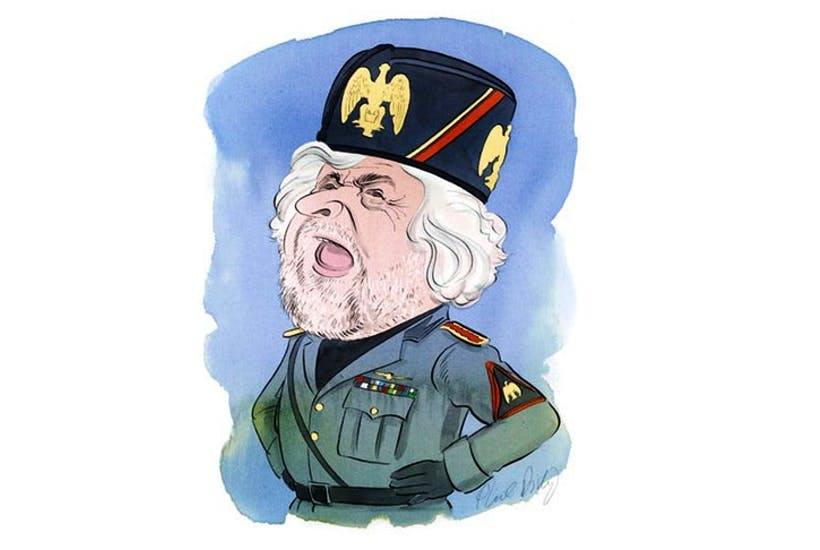

A couple of years back, while writing my book Radicals, I secured an interview with Beppe Grillo, leader of the Italian Five Star Movement. M5S (its Italian abbreviation) is the radical anti-establishment party that’s on track to top next week’s general election. We met in the restaurant of the hotel he always stays when in Rome. There was a small crowd outside as I walked in, hoping to get a glimpse of the man. Beppe wandered in late – he enjoys daily siestas – waving his smartphone. ‘This,’ he said, as he sat down, ‘this is what changes everything!’ Then something weird happened. Before I’d even pressed ‘record’, he picked up the small spoon that came with his espresso, and starting staring at it, making it bend like a la Uri Geller. He looked at me, and then back at the spoon, and then back at me, and laughed.

Beppe has been one of Italy’s best-known comedians since the 1980s, partly due to his wildly popular TV show. Back in 2009, frustrated with Italian politics but enamoured with blogging, he set up Five Star, hoping to spark a digital revolution in politics. Thanks to the internet we can do away with political parties and corrupt media, he said. Big decisions can be taken on my blog via frequent plebiscites. Ordinary people can set up their own local branches of the group on www.meetup.com and select their own candidates. Five Star crashed through Italian politics like a tsunami. By the 2013 election, it won roughly 25 per cent of the vote. It has come first in the last 96 consecutive opinion polls. (Although it still might not win the upcoming election because of a centre-right alliance).

People often say that Trump is the perfect politician for the digital age. I also say that. But Grillo is a better sign of what’s coming. He’s the personification of the problems and opportunities that digital technology lays out to our ailing democracies. On one hand, he’s using all the new kit to get more people involved, circumnavigating crony party politics, and rallying people together. Bravo. But he’s also a populist iconoclast who wants to smash the system. ‘Politicians are parasites,’ he says. ‘We should send them all home!’ A few years back he held a successful ‘Fuck Off Day’ directed at the establishment. He called previous Prime Minister Monti ‘Rigor Montis’. To be fair, that’s quite a good one.

Like all populists he pits the good, honest, ordinary citizen against the out-of-touch professional political class. He vows to represent the pure people, the ‘we’, against the morally corrupt elite, the ‘them’. An authentic and honest voice in a nihilistic political world of spin and self-interest. This is a dangerous narrative that can lead to some dark corners – anything can be justified in the name of the people. Some of the ‘Grillini’ are anti-vac. There have been summary dismissals of MPs from the team surrounding Grillo, which is known as ‘the staff’. Buzzfeed’s Alberto Nardelli found last year that the all-important blog is a den of misinformation.

Over the last few months Grillo has stepped back, distancing himself a little from the movement he founded, although he’s still the ‘Guarantor’, whatever that means. But there will be plenty more like him, because digital populists like Grillo are more in tune with the time. Everything online is fast and personalised: access to everything and everyone, to millions of webpages, all the goals, all the baby pictures, and all for free. You zoom in, you zoom out, swipe, tap and Insta-chat with a distant relative. The result is a growing disconnection between the choice, speed and freedom that characterise our lives as consumers, and the compromise and tedium of plodding politics. People like Grillo promise to use tech to smash through boring old politics and give us answers and solutions with the immediacy and perfection of an Instagram filter.

In the coming years we will drift toward more Five Star style politics. More direct democracy, more plebiscites, more internet votes. There are good bits to this, as there usually are with bad ideas. But beware the darker side. Internet direct democracy and populism fit hand in glove. Populists claim to be the voice of the people, fighting a corrupt, powerful and professional elite. The internet is the ideal direct line to those honest, decent, hard-working people, circumnavigating the self-interested establishment parties and media. Every populist, whether now or in the past, believes they speak for the downtrodden and quiet man on the street, the silent majority. They always think they possess some version of what the philosopher Rousseau called the volonté générale – that vague, dangerous notion of the people’s will, to which a leader can attach himself and do whatever they wish. Here’s a prediction: any new populist party created in the coming years will promise to introduce more referendums and digital voting for members. They will say that it’s ordinary people speaking out against establishment, and hail it as a new way to break the slow, corrupt ‘system’. They will obviously then ignore whatever the people say if they don’t like it. And they will use it as a way to slice through disagreements. It’s the will of the people, they’ll say. Boring old judges and ‘processes’ and quangos and regulations be damned.

Some commentators have compared Grillo to Mussolini, which is unfair. Yes, they both promised to escape straight jacket of left and right, they both embraced new tech. I’m sure Mussolini would have loved Facebook – he would have said it was a new way to reach the people, without going through the corrupt system. But Il Duce killed his opponents, while Beppe merely insults them. He’s no fascist. I think he’s a true believer in the emancipatory power of the Net. But it’s not surprising that some journalists have noticed the similarities – including in this magazine. When I put it to Beppe that he had been compared to Il Duce, he just laughed and shrugged his shoulders. ‘You cannot compare a thing like this! Even if Mussolini was an extraordinary comedian, it is him who resembled me, in being a comedian!’ I think he meant that he still sees himself as a comedian rather than a politician – and that Mussolini himself in the end was frequently mocked and caricatured. I’m not entirely sure. But it wasn’t a particularly funny joke.

Jamie Bartlett is Director of the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media for Demos. He is the author of Radicals and The Dark Net.