Does Joe Biden write his own speeches? Surely not. Yet his campaign says Biden was his own speechwriter for the address he made to the nation a week after the election, when he stressed his campaign theme: ‘We must restore the soul of America.’ The Soul of America is the title of a book by the historian Jon Meacham and the New York Times figured out that Meacham had helped with the speech. The campaign’s national press secretary, TJ Ducklo, was forced to concede that, yes, Biden had ‘consulted a number of important, and diverse, voices as part of his writing process, as he often does’. Though Ducklo, sounding a little ticked-off, insisted: ‘President-elect Joe Biden wrote the speech he delivered to the American people on Saturday night.’

Really? Crafting a speech takes a long time. For Biden to do this personally would be only a little less surprising than if he were typing his own press releases or answering his own telephone. (After leaving office, Lady Thatcher would pick up her phone when it rang — someone said it was like Napoleon having to saddle his own horse.) Ducklo could have more artfully called it Biden’s speech without stating that he literally wrote it. I asked the campaign if he had really meant to say this. They did not respond. Having so frequently condemned Donald Trump as a liar, it would be a pity if Biden and his team were to start out with a lie, however small, if that’s what it was.

Because Biden has a history with speeches. His plagiarism of a speech by the British Labour leader Neil Kinnock is still one of the best-known episodes of his 50 years of public life. It destroyed his first run for the presidency, in 1988. Perhaps it’s unfair that this single incident should be brought up again (and again). But for most politicians, the ‘arc lights of history’ — or at least of concentrated, national media attention — come to rest on them only a handful of times, usually during crises of their own making, and these moments end up defining them. You might think that Biden had been let down by his speechwriting staff, someone lifting the Kinnock passage wholesale without telling the boss. But it was all Biden. Or rather it wasn’t.

The definitive account of Biden’s plagiarism of Kinnock is in Richard Ben Cramer’s What It Takes. This is more than 1,000 pages about most of those who ran for the presidency in 1988. Reading it marks you out as a political obsessive, like plowing through all four volumes of Robert Caro’s The Years of Lyndon Johnson. Cramer gives you not just the detailed personal histories of the candidates but of their parents and their grandparents, too. But What It Takes is a masterpiece and all the more interesting now for the chapters on Joe Biden. Here is Joey Biden, 10 years old, rolling between the wheels of a moving dump truck for a dare. Here he is in Catholic school, turning on a bigger kid who was mocking his stutter and grabbing him by the neck. Here is Joe Biden, now in college, telling his girlfriend’s mother that he’s going to be president, adding helpfully, ‘of the United States’.

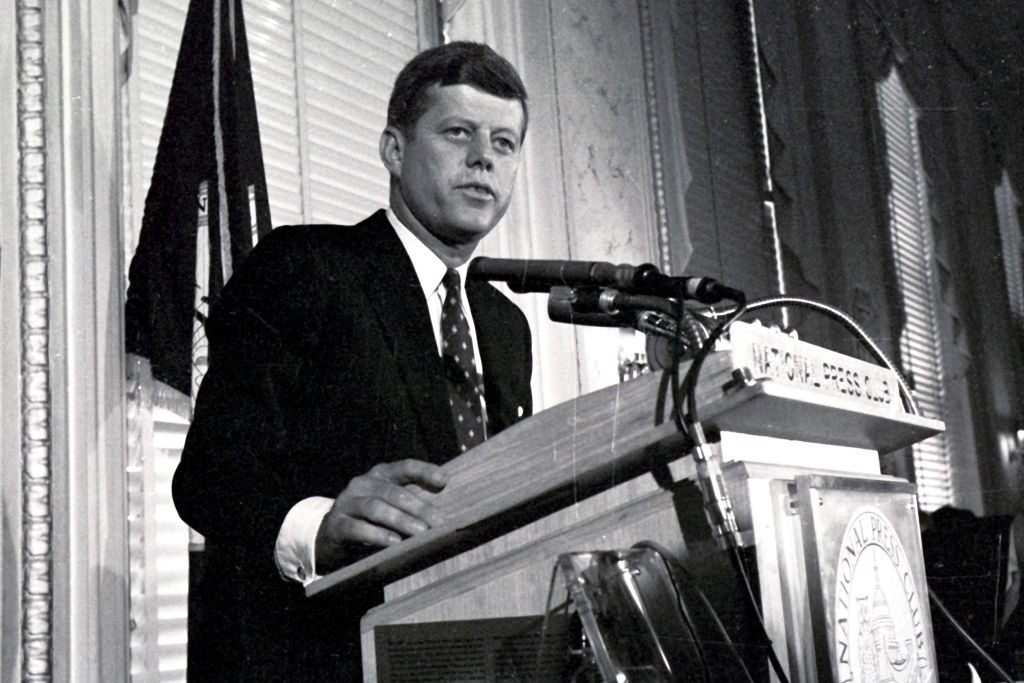

And here is Biden in 1988, struggling to find a message despite a room full of expensive political consultants. Someone shows him a tape of Neil Kinnock talking about why he was the only Kinnock ‘in a thousand generations’ to go to university — because he’d been given ‘a platform upon which to stand’. Biden loves it. That’s his message. He takes the VHS tape home and watches it over and over again. Later, straight off the plane in Iowa, he doesn’t have the closer to a big speech. In the van, he asks for paper and pen and has his ending done by the time he gets there, 15 minutes later. ‘He knew that stuff from the Kinnock tape like a song in his head…he started writing it down, without hitch or pause.’ Then, in front of the audience, he tilts his head and asks: ‘Why am I the only Biden in a thousand generations…?’

Cramer writes: ‘It was uncanny: it wasn’t just the words — it was every gesture, every pause. And not one mention of the name Neil Kinnock!’ Biden might have got away with it if he had not spoken about ‘my ancestors who worked in the coal mines of north-east Pennsylvania’. He had no coal-miner ancestors. Biden didn’t just steal Kinnock’s words: he stole his life. This wasn’t the first time Biden was caught plagiarizing. He had been in trouble in college for copying five pages of an academic paper, footnotes and all. But this was as if Biden was so immersed in the fantasy version of himself that, even as he said things some part of his brain knew were lies, he just couldn’t help it.

This, too, had happened before. Several times, Cramer watched Biden telling audiences about ‘marching’ with the civil rights movement, as if he had joined arms on the bridge to Selma. He had not marched, though he did once walk away from a lunch counter in Delaware that wouldn’t serve a black friend. This is a common pathology among politicians, Ronald Reagan ‘liberating’ the Nazi death camps, Hillary Clinton ‘under fire’ in Bosnia, Donald Trump ‘predicting’ Brexit at Turnberry. But do these incidents in Biden’s past reveal some immutable truth about his character? A new biography of Biden by Evan Osnos shows him in front of an audience in Selma in 2013, saying he had been involved in civil rights only ‘in my state, in a small way’ and then apologizing: ‘I should’ve been here.’ And Osnos finds an interview that Biden gave in 2007, taking responsibility for the Kinnock speech: ‘I didn’t deserve to be president.’

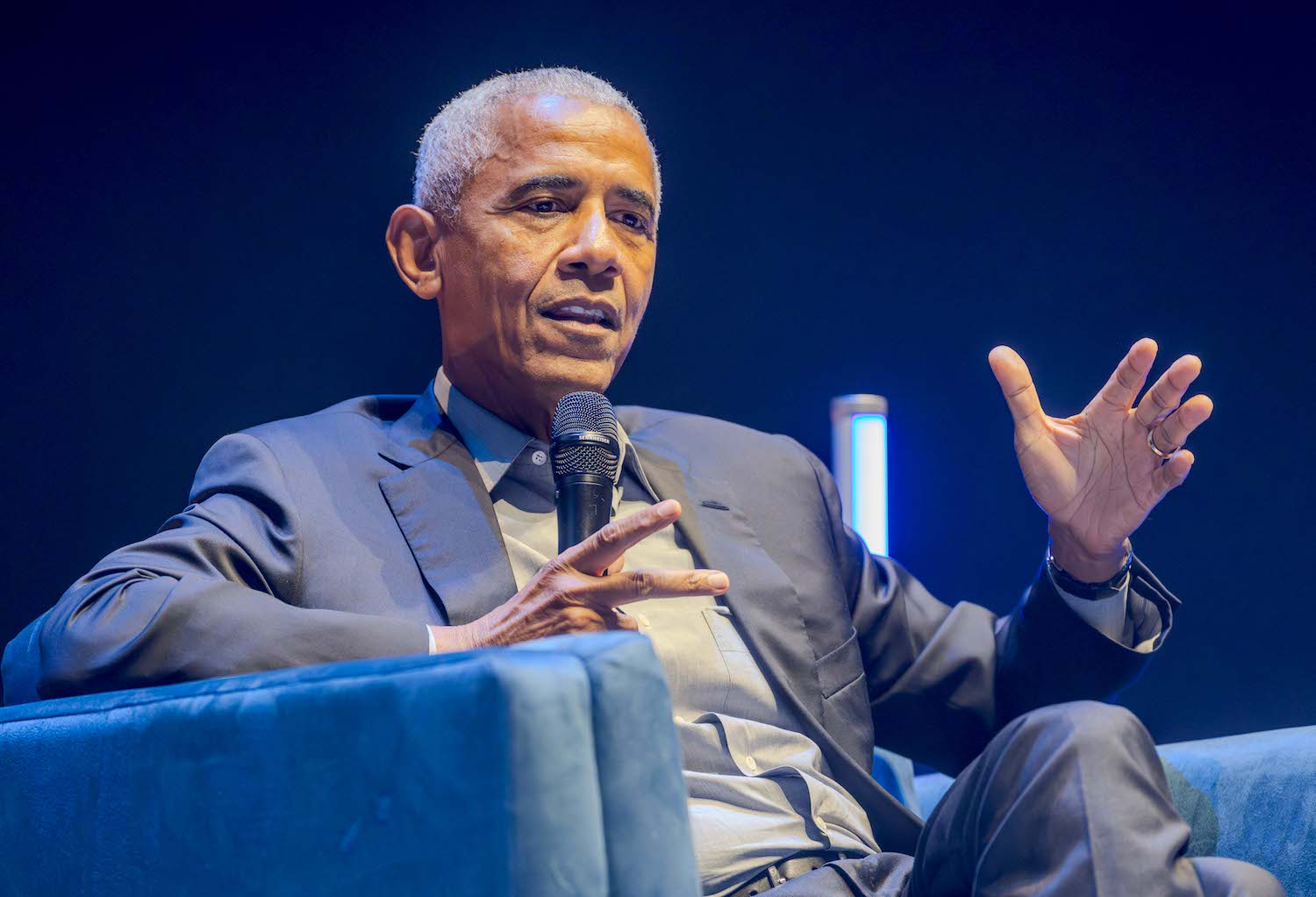

Some of those who have known Biden for decades tell me he’s still the same guy who used to take the Amtrak from Wilmington: an unremarkable senator from a small state, tough, loyal, energetic, sometimes a bit glib. Others say he grew and changed in his years as Barack Obama’s vice president: less prickly, no longer consumed by ambition. Neither version of Biden is a systematic thinker or a visionary leader. After Donald Trump, that matters less than whether America now has a president who prefers truth to lies. Biden’s long political struggle suggests that at least he knows the difference.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2020 US edition.