Bill Clinton, in a speech heralding China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2000, remarked that ‘by joining the WTO, China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products. It is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values, economic freedom. The more China liberalizes its economy, the more fully it will liberate the potential of its people — their initiative, their imagination, their remarkable spirit of enterprise. And when individuals have the power, not just to dream but to realize their dreams, they will demand a greater say.’

It is by now glaringly obvious that this vision didn’t come to pass. For far too long, ‘End of History’ hubris dominated western engagement with China, and hubris led to nemesis. Instead of importing democratic accountability, China exported its model of authoritarianism to the world. It would be one thing for America’s economic hegemony to finally be challenged in the global arena. But China isn’t merely an economic competitor with clashing national interests. It is a geopolitical rival whose values are mutually incompatible with those of the United States and its allies.

The domestic clashes currently dominating our news cycles are drowning out the fact that the US-China bilateral relationship is the most consequential issue of our time. If you think I exaggerate, look no further than the myriad ways the Chinese Communist party has been subtly waging its offensive on various fronts — economics and finance, information, technology, global diplomacy, and education, in what former Air Force Brigadier General Robert Spalding has termed a stealth war. This version of modern warfare is fought not with bullets and bombs but with bytes and pixels, and dollars and yuans. For the average American, it has and will continue to have a real impact on everyday life, from the availability of jobs to the price of certain goods, from the tech apps you can use to what you can and cannot say on social media (as Houston Rockets general manager Daryl Morey found out), from the supply of fentanyl decimating our communities to what the internet will look like, from the content of your university courses to the plots of the movies you consume.

Racial fault lines and fissures in our culture wars are exploited by armies of propagandists and trolls employed by a Chinese state which seeks to further weaken an already fragile social fabric. This materializes as chaos on the streets and edges the country closer to a civil war. American businesses are learning their lessons too as the CCP escalates corporate intimidation tactics, using access to its huge market as leverage for its political bidding.

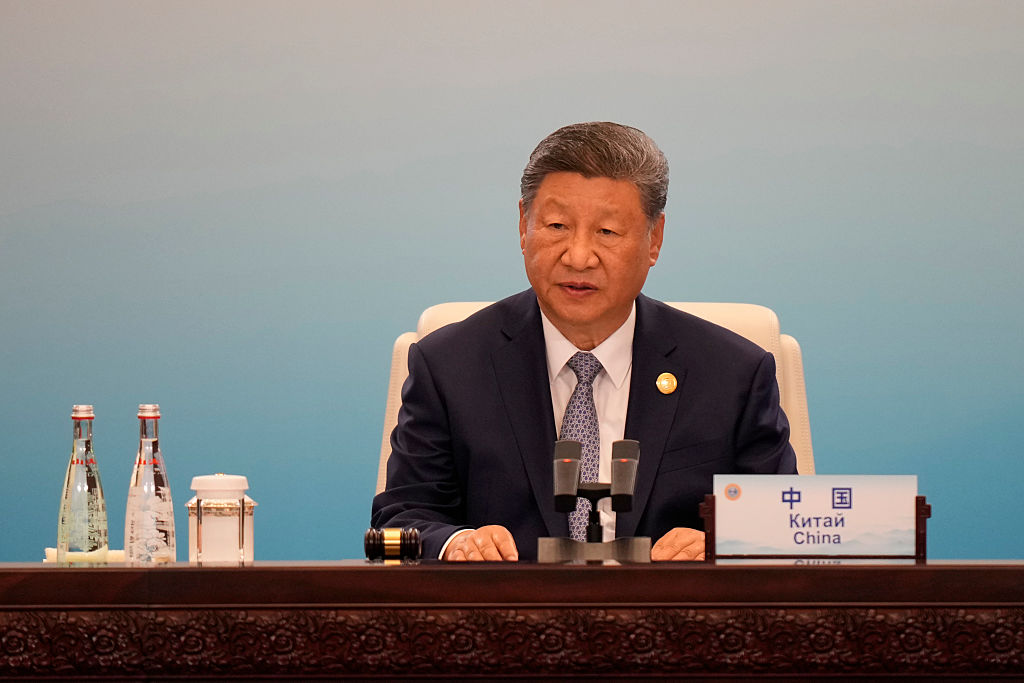

In July 2019, the American public identified climate change and Russia (including cyber attacks) as the biggest threats facing the nation. According to the Pew survey, only 54 percent then viewed China as a global threat — and this was after massive pro-democracy protests had erupted on the streets of Hong Kong. Exactly one year later, public opinion has shifted dramatically, with 73 percent of Americans now viewing China unfavorably. Much of this change can be attributed to how China handled the COVID-19 pandemic. Countless signs have long shown the CCP’s increasing resistance and hostility to the rules-based international order and its refusal to reform and liberalize — the 1989 crackdown in Tiananmen Square, the erection of the Great Firewall, the rise of Xi Jinping and his increasingly autocratic rule, the erosion of civil liberties in Hong Kong, the militaristic expansionism in the South China Sea, the outright repression of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, the brazen hacking of US companies and government institutions, the list goes on. But for a majority of Americans, it was COVID-19 that brought the idea of China as a geopolitical adversary and threat into sharp focus.

The cover-ups, the silencing of whistleblowers and misleading statements in the early days of the viral outbreak in Wuhan drew the ire of many. Several actions that followed, such as the expulsion of American journalists from Beijing and the censorship of academic research on the actual origins of the coronavirus, were simply not in line with the conduct of a country that was purportedly committed to transparency and accountability. By the time Western governments scrambled to counter the pandemic on their shores, the over-reliance of our industrial and medical supply chains on China became painfully apparent. The shortage of personal protective equipment, almost all of it made in China, revealed the vulnerabilities of outsourcing manufacturing of crucial supplies to a geopolitical rival, especially as various European countries reported receiving defective test kits and masks from China. Most recently, a prominent Chinese academic urged the CCP to weaponize exports of medicines and drug precursors in response to US efforts to limit the global growth of Chinese telecom company Huawei. These disturbing developments have precipitated widespread calls to decouple America’s economy from China’s. While full disentanglement is impossible without significant upheaval, the need to achieve and maintain supply chain security has at least become a realistic and necessary goal in the public consciousness.

Another important aspect in the US-China standoff is the battle for the soul of the internet and emerging new technologies. The two countries have competing visions for the world wide web. Should it be a decentralized, open internet that empowers ordinary people? Or a centralized, firewalled internet that’s also a tool of political control? The Trump administration’s move to ban TikTok and WeChat prompted critical headlines about the end of the open internet and the dawn of the ‘splinternet’, where cyberspace is balkanized into several geopolitical entities circumscribed by digital borders. Such analyses overlook that, from a trade reciprocity standpoint, China has since 2009 banned US social media networks and content platforms including Facebook, Github, YouTube and Netflix. So uncoupling our internet from China’s access is less about ‘sinking to their level’ than it is about enforcing an ethos of openness.

Then there’s the race to develop and deploy 5G, a race that the US has been losing, much as it did in the Sputnik era. This next generation mobile network isn’t merely an upgrade in bandwidth and download speeds. 5G technology will enable the so-called Internet Of Things, which will power everything from self-driving cars to smart electrical grids, autonomous manufacturing to long-distance surgery. While 5G dominance is of huge commercial interest, the US risks ceding the field if it cannot compete with Chinese telecom giants, Huawei and ZTE. Because national law mandates that every Chinese company is obliged to hand over data on both domestic and foreign networks to the Chinese Communist party as they see fit, these firms must be seen as an extension of the Chinese state and an instrument of China’s broader global political ambitions. And so what it comes down to is that the contest for 5G is not just a strategic imperative but a moral one. If the Chinese have a hand in constructing our 5G infrastructure and networks, they could conceivably control every piece of our private and financial data.

[special_offer]

For the last four years, the Trump administration’s approach to China has departed sharply from the previous decades of engagement that saw every administration greet the rise of the sleeping giant as, in the words of Joe Biden, ‘a positive development’ instead of as an existential threat. The White House has taken bold economic actions against China, tearing up trade agreements and launching a trade war, using economic pressure (tariffs) to demand change. As tit-for-tat battles and escalating diplomatic tensions characterize US-China relations, it wasn’t surprising to see Republicans make China one of their key campaign issues in their convention last week. China featured heavily over four nights of the Republican National Convention. Who could forget the moving sight of blind Chinese human rights lawyer Chen Guang Cheng addressing the podium, castigating the policy of appeasement of former administrations which he said had ‘allowed the CCP to infiltrate and corrode different aspects of the global community?’ Several other speakers used anti-China rhetoric, among them Sen. Marsha Blackburn, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Sen. Tom Cotton. President Trump himself spent a good portion of his speech attacking Biden’s record on China and patting himself on the back for his own policies which brought jobs home and recalibrated the bilateral trading relationship.

In contrast, China was barely a single blip on the Democratic National Convention radar. The C words just got one mention in Joe Biden’s acceptance speech. By centering China and outlining a clear conflict between the two countries and two systems, the Republicans have painted the Democrats in a corner: if voters agree that this election comes down to America vs China, then the choice should be obvious.

The timing here is crucial. The United States has been asleep at the wheel for four decades. It profoundly miscalculated the consequences of its economic engagement with China. From now on, America’s strategy must involve forging a new global alliance among democracies that buy into the principles of free expression, human rights, free trade, and the rule of law. Contra to what Sen. Tom Cotton suggested in his speech, America cannot continue to ‘stand alone’ in countering China’s rising power and growing influence. A global realignment around two axis is taking place, as countries self-sort into distinct blocs around China or the United States. So as you head to the voting booth this November, ask yourself: who do you trust more to fundamentally decide what the 21st century, and your life in it, will be like?