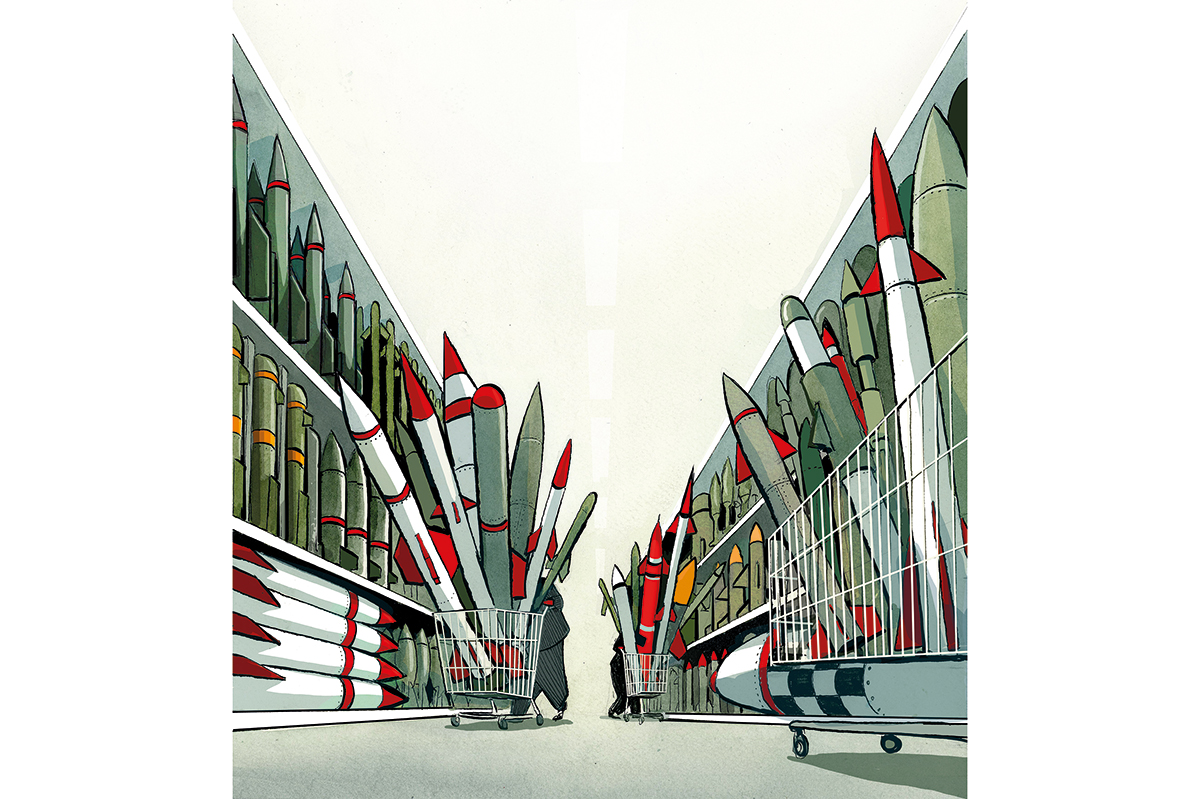

If 2020 is generally accepted to be a global annus horribilis, then it is perhaps fitting that the Islamic Republic of Iran’s ability to do mischief has seemingly just received a hefty boost. On Sunday morning, the UN lifted its 13-year long arms embargo on the Iranian armed forces. Iran is now (technically at least) free to buy and sell arms in the international marketplace.

It seems an odd time to be easing up on Iran. At the end of last year, just before coronavirus set in, the regime was making an excellent fist of massacring its own people. It machine-gunned them from rooftops, it beat them in the streets, and then hauled away the corpses so they couldn’t be examined. Now it’s being allowed to buy weapons and technology to do all these things even more fastidiously.

The truth is that the embargo was lifted because that was one of the terms of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), between Iran and the P5+1 (the five Security Council powers and Germany) together with the European Union. Known commonly as the ‘Iran nuclear deal’, this sought to end the crisis between Iran and the West that had rumbled on over Tehran’s nuclear program since the turn of the century. The deal was simple: Iran accepted curbs on its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief.

It didn’t last long. Donald Trump had castigated the deal before he was even elected and, on May 8, 2018, he unilaterally and formally withdrew the United States from the deal. ‘It is clear to me that we cannot prevent an Iranian nuclear bomb under the decaying and rotten structure of the current agreement,’ he said. The Iranians squawked predictably about the perfidiousness of Washington, but they did not withdraw. Neither did the Europeans; and so the deal stumbles on — at least in theory — and Iran got sanctions lifted as promised.

But this is not enough. In truth, the deal is almost dead. Iran is now no longer receiving the economic benefits it was expecting — largely because the United States has reinstated its unilateral financial sanctions. For its part, Iran now applies a strategy of ‘less for less’: less economic benefits equals less nuclear limitations. Things are now pretty much going directly in reverse.

As Clément Therme, a research fellow at Sciences Po in Paris, observes: ‘the end of the UN arms embargo is more a symbolic than a political victory for the Islamic Republic.’

Iran is technically free to buy arms from whoever it wants but the truth is that Washington will apply unilateral economic sanctions to any potential entities who sell it weapons. Even Iran’s natural vendors here, China and Russia, and specifically their banks, will likely be reluctant to support such deals. The cost-benefit analysis is clear: it’s not worth it.

Even the Europeans, who have done almost everything to keep the JCPOA, have not countenanced exporting weapons to Iran. They may take a softer line than Washington but they have their own issues with Tehran. For Emmanuel Macron, this is no longer just about nuclear. Iran’s ballistic missile program, regional policy and human rights record must also all be on the table. Nothing marks a clearer break from Barak Obama’s policy of ring-fencing nuclear issues to get the JCPOA done than this. As Therme notes: ‘France is aligned with the US on the substance of their problems with the Islamic Republic. They only disagree on the methods.’

[special_offer]

Even if Washington didn’t object so vehemently, the fact is Iran simply doesn’t have the money to go arms shopping. Its economy was dire before coronavirus hit. Now it’s on life support. Iranians are already enraged that their rulers prefer to splurge billions on foreign adventurism rather than pay for doctors. They want better schools, not more drones.

And another uncomfortable truth for Tehran is that the only way they can start to piece together some sort of economic recovery is if they can restart oil exports properly. And that, of course, can only come with a new diplomatic compromise with the Great Satan.

Iran remains boxed in. It’s diplomatically isolated, internally at war, and becoming poorer by the day. It needs options, and it needs them to come from the United States: It’s not just liberals and progressives who are pinning their collective hopes on a change of US president come November.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.