The Mueller report did not bring down Donald Trump. The president will not be impeached before the 2020 election, and it is clear – in spite of the hopes of the good men, women and nonbinary soldiers of the Resistance – that he is not a Russian superbot manufactured in a cutting-edge information warfare lab in the dark belly of the Kremlin. Trump is not the Manchurian president.

An ominous question emerges for liberals: who is Donald Trump, if he is not Vladimir Putin’s dogsbody? What the hell are we going to do with him? Why is he still fouling up our government? The pack howls, but in the four years since Trump descended the golden escalator from the world of television entertainment to the world of political entertainment, they have yet to catch him.

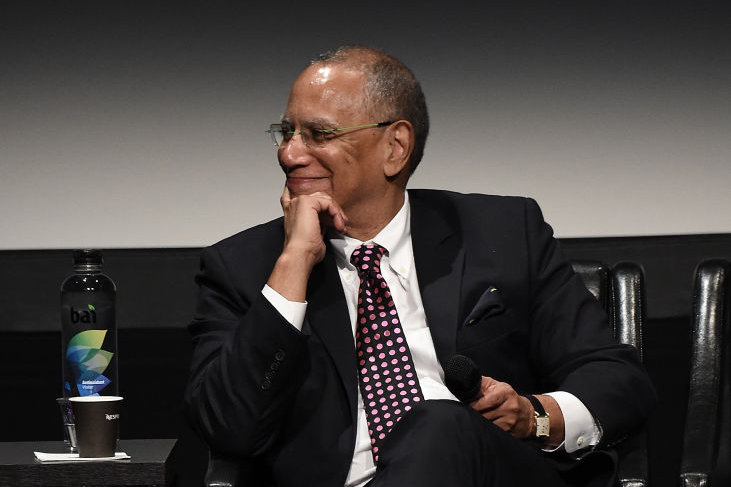

Over the summer there has been a decisive shift away from the Russia storyline, towards a focus on the president’s alleged ‘white nationalism’. Here is Dean Baquet, executive editor of the New York Times, reflecting on this shift in focus:

‘Chapter one of the story of Donald Trump, not only for our newsroom but, frankly, for our readers, was: did Donald Trump have untoward relationships with the Russians, and was there obstruction of justice?’

But then Mueller failed to stake the vampire: ‘Our readers who want Donald Trump to go away suddenly thought, “Holy shit, Bob Mueller is not going to do it.” And Donald Trump got a little emboldened politically, I think. Because, you know, for obvious reasons. And I think that the story changed.’

Saying that the ‘story changed’ is a very polite way of saying that it wasn’t worth the chip paper it was printed on. Baquet’s ‘vision’ for the paper in the next year is all about race. ‘How do we write about race in a thoughtful way, something we haven’t done in a large way in a long time? That, to me, is the vision for coverage. You all are going to have to help us shape that vision. But I think that’s what we’re going to have to do for the rest of the next two years.’

None of Baquet’s comments were intended for public consumption. They were made at an employee town hall last Monday, a transcript of which was leaked to Slate a few days later. (Those who subscribe to the New York Times read some neat recipes, some lovely travel guides and plenty of lunatic op-eds, but they are not invited to see how the paper sketches out its news coverage months before the news has happened.)

The word ‘narrative’ is used about half a dozen times in that town hall transcript. Baquet’s notion of the paper having a ‘vision’ is similarly postmodern. The clearest parapraxis of all is when he says ‘Chapter One’ of the ‘Donald Trump story’. Do the Times report the news any longer, or are they ‘self-consciously crafting the first draft of history’? As Bruno Maçães put it, ‘this no longer feels like journalism. It’s novel writing.’

Last week also saw the launch of the Times magazine’s ‘1619 Project’, which is far more ambitious than mere journalism too: ‘The 1619 project is a major initiative from the NYT observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery. It aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding.’ Essays in the series so far have attempted to demonstrate that America’s prisons, dietary habits, music, traffic jams, medical practices, healthcare systems, wealth gap and entire political economy, are all bones bound to one body: slavery, ‘the country’s true origin’. Somebody had better dig up the Founding Fathers to let them know the Times has figured out that the true founding of the USA was 157 years before they thought it was.

Novel writing this may be, but the Times and Baquet are hardly original. Plato argued that the ruling class were allowed to lie for the best interests of the state:

‘It will be for the rulers of the city then, if anyone, to use falsehood in dealing with citizen or enemy for the good of the state; no one else must do so.’

And Machiavelli (who else) warned the Prince to act ‘a great feigner and dissembler.’ But Plato was writing speculatively; Machiavelli’s advice was to a ruler trying to retain power amid the brutal city state jostling of 16th-century Italy. Neither of them are talking – as Baquet did – about the construction of truth. They simply argue that there are times when the truth is best skirted or ignored.

The thinker who really hovers over own era, as Peter Oborne points out in his useful book The Rise of Political Lying (2005), is Michel Foucault. If you have a machete to hand, prepare to use it to cut through the Frenchman’s inimitable prose:

‘Truth is to be understood as a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution, circulation and operation of statements. Truth is linked in a circular relation with systems of power which produce and sustain it, and to effects of power which it induces and which extend it.’

Truth is there to be created by the powerful. This is a seductive and flattering notion, particularly for wielders of power. If, as Oborne notes, ‘reality and presentation’ become identical, then all kinds of managers, in all kinds of industries – including journalists – are free to shape ‘narratives’ according to their own interests.

Here are two ‘narratives’ for you to consider:

a) Donald Trump is a New York Republican who became president by accident. His primary interest for future historians will be his use of new digital technologies like Twitter.

b) Donald Trump is a white nationalist. His primary interest for future historians will be his mobilization of white resentment to build a Fourth Reich in North America.

Narrative A is probably closer to the truth than Narrative B. But it’s certainly less exciting than Trump being Hitler, or a Russian agent. Narrative B is far more dramatic. It’s darkly historic. It’s going to be all over the New York Times for the next year. It shifts books. It drives engagement. It gets people out on the street and to the voting booths.

There is an obvious objection to this: aren’t the president’s lies more important than those of the Times? Trump lies with breathtaking alacrity, there’s no denying or excusing it.

But the most interesting thing about this presidency is that reactions to Trump have unveiled truths far greater than any lies he has told. Like Tony Montana at the end of Scarface, Trump somehow always tells the truth – deep truths about America – even when he lies.

You always kind of knew that movement Republicans like Paul Ryan didn’t give a damn about working people, and after watching their behavior during the first two years of this presidency, you know it for sure.

You always kind of knew that since the 1990s the foreign policy establishment believed the answer to every question was ‘war’; and after watching their desperate attempts to drag the country into a Persian quagmire in the last three years, you know it for sure.

You always kind of knew that CNN and the Times were more liberal than they allowed their public faces to show; now, they don’t even bother to hide their biases and you know it for sure.

It’s like the Parable of the Good Samaritan all over again. Instead of a beaten traveler lying in the gutter, it’s Donald Trump standing on the corner of a sidewalk, trash talking everybody who comes by.

How they react to him tells you who they really are, and what they really want. The ‘narratives’ they weave, and the facts they’re happy to omit from those stories reveal even more.