You know what they say about America: beautiful for spacious skies, for amber waves of grain and purple mountain majesties above the fruited plain. But its fruited plains – specifically its vineyards – and amber waves of grain aren’t doing her neighbor to the north much good at the moment – at least not in the beverage department.

In the Loyalist province of Ontario, just as in la belle province of Québec, no California wines have graced the store shelves for more than half a year. American tipple is out. As far as eastern Canada is concerned, the minions of Francis Ford Coppola crush grapes in vain, all is quiet along the Yakima and it matters not whether pinot noir still reigns supreme in the Willamette Valley. Ask not for whom the Napa flows; it’s not for thee.

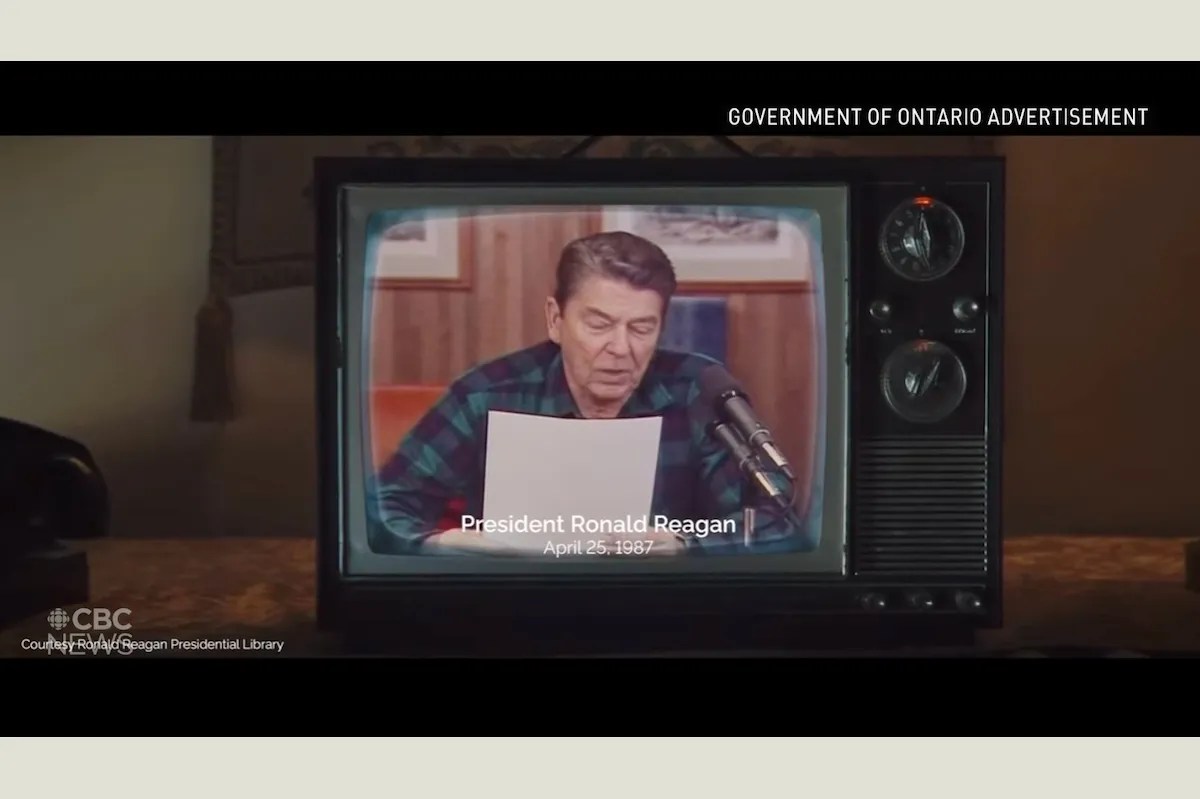

Last spring, as part of a pushback against Trump’s tariffs, a number of provinces, including Ontario, Québec, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, put a ban on the sale of American alcoholic beverages. The move didn’t soften the Trumpian heart, nor did it weaken his resolve. But it did leave Canadian consumers scratching their heads, wondering why all the rum was gone from the Kraken shelf.

It had, as it turned out, been strong-armed off the displays, along with California wine and Tennessee whiskey. It was not, as in Pirates of the Caribbean, used to build a massive distress-signal fire, but packed sternly away into warehouses on pallets, sealed in layers of plastic wrap and red tape. Shops weren’t even allowed to sell off the stock already imported.

Alberta, growing into its future role as the voice of Canadian common sense, soon rescinded the ban, but others – notably Ontario, whose short-sighted premier Doug Ford came up with the plan in the first place, and Québec – stayed stuck on the program.

How times change. Once, America was the country dumping tea into the harbor, prohibiting alcohol, pouring Champagne down the drain and generally playing havoc with the nation’s drinking supply. Back then, Canada sat cheerfully up north, light-hearted and reasonable, sipping on tea, whiskey, bubbly and anything else it fancied, while happily expanding its national economic activity to bootlegging and the manufacture of ginger ale.

Indeed, if it weren’t for the American temperance movement, Canada Dry might never have gotten off the ground. Its ginger ale sold well in Prohibition-era America, because the extra sugar in ginger ale was just the thing to cover up the taste of bathtub gin.

Canadians are just as easygoing as they used to be, but it’s now their leaders’ turn to launch into political theatrics, loudly banning American drinks until morale improves. As most Americans don’t worry a huge amount about Canada, let alone what people drink here, the main audience for this little bit of performative whimsy is, sadly, the citizens of Canada. It’s a virtue-signal, intended to make Canadians feel – every time they go grocery shopping – that Something is Being Done, however pointless.

If you try to buy American products online from the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (the Crown corporation that controls the import and distribution of alcoholic beverages) you’re told, rather sanctimoniously, “This US product is no longer available in response to US tariffs on Canadian goods. Check out our recommended Canadian alternatives.”

Supporting Canadian winemakers and distilleries (and there are some very good ones, such as Grey Monk in BC or Eau Claire Distillery in Alberta) is not the problem. It’s the hypocritical pretense that the government is helping Canadians, when actually, it’s capitalizing on one more petty method of controlling them. As the Jack Daniel’s man said, why not simply impose a counter-tariff?

Still, they can go ahead and ban it if they want to. The Canadian smuggling tradition is too good to lose. Canadian author Farley Mowat recounts in The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float, published in the 1960s, how he was invited to participate in a smuggling venture running alcohol between Saint-Pierre and Miquelon and Newfoundland. As Mowat was, in his own words, in favor of anything that takes the mickey out of duly constituted authority whenever that authority intrudes on the freedom of the individual, and (also in his own words) in favor of inexpensive booze, he agreed.

The local lads on Saint-Pierre helped him prepare his craft: on the sailboat deck, they installed wooden troughs to hold the crates – hinged, so that with the simple pull of a rope, the cargo could be jettisoned in case of visitation by the coast guard.

In the dark of night, the crates were delivered to the boat and installed in the troughs, each one lashed to a heavy sack. The practice was to tie bags of fisherman’s salt, known as “insurance,” to the smuggled goods. If the crates were thrown overboard, the heavy bags of salt would drag them down to the bottom of the sea. In 15 to 24 hours, depending on the size of the bag, the salt would dissolve and the crates would pop back up to the surface, ready to be collected by any boat that happened to be lingering in the area.

Out they sailed toward the shore of Newfoundland, ill-gotten goods lashed to the hinged contraptions on deck, keeping a weather eye out for the cops. Sure enough, the RCMP boat roared down upon them in the fog, siren wailing horribly. Mowat and his pal hurled themselves upon the ropes, tossing everything into the sea.

They were greeted with self-satisfied smiles from the constabulary, who noted that not only had they tossed their cargo unnecessarily, having made it safely into international waters, but that they, the fuzz, were on to the salt bag game and intended to lie in wait on that very spot until each and every crate floated back up. “And we’ll sink every last one of them!” they promised.

Mowat and crew headed off despondently to the shores of Selby’s Cove, where they were greeted with wild enthusiasm. As it turns out, their operation was only a decoy, and the jettisoned cargo consisted of rocks, attached to sacks not of salt, but of sand. The real operation arrived on shore a few hours later: three boats packed to the gunwales with kegs and cases of smuggled alcohol.

In the subsequent rejoicings, it is hard to say if anyone spared a thought for the poor coast guard officers, eyeing the waters that never give up their dead.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply