The New York Times recently released its annual list of America’s Top 50 restaurants – and the perfectly predictable honorees highlight just how beholden the restaurant industry is to the tastes of a would-be cosmopolitan class. The casually refined, vaguely ethnic-fusion cuisine that you stumble upon even in America’s most provincial places is rife.

From New York to Los Angeles and everywhere in between, America’s restaurant industry has never been more diverse. Yet somewhat counterintuitively, it’s also never offered more of the same.

Often, these restaurants propose some mix of French staples (think mother sauces, patisserie) or Italian comfort food (pasta, pizza) fused with Latin, Asian and/or Middle Eastern flavors. Other times, lowbrow American grub gets ironically elevated with a flourish of chef-y technique.

For example, Colorado’s Bin 707 Foodbar offers an elk tartare flavored with Japanese plum and a French béarnaise served with a side of Italian focaccia. Pair it with the miso chimichurri pizza.

Aesthetically, dining rooms are often hypermodern or performatively rustic, but either way, they feel overdecorated

At Knoxville’s JC Holdway, try a spicy watermelon gazpacho before a bowl of bolognese pasta with cornbread crumble. At Diane’s Place in Minneapolis, sample the titular chef’s award-winning French pastries before a hearty Asian meal “inspired by her Hmong heritage.” And at San Antonio’s Isidore, who wouldn’t love some popcorn chicken in a decadent velouté or a slice of Southern buttermilk pie peppered with the umami notes of fennel?

These are all vastly diverse dishes, yet the overarching “concepts” blend together. Click on any restaurant’s “about” page and there’s often a great emphasis on local and sustainable sourcing despite the foreign flavors. It’s also likely to feature a morally loaded tale of the chef’s culinary journey – embracing their heritage, overcoming assimilation struggles and crafting a “new authenticity” for themselves.

Aesthetically, the dining rooms are often hypermodern or performatively rustic, but either way, they feel professionallyoverdecorated. Even the concept of a “concept” restaurant has become overwhelmingly banal. Gone are the days of the traditional steakhouse, luxurious French prix fixe, or even a classic pub or diner (although, in fairness, a handful of these still made the Times list). They’re considered stuffy, dated and, perhaps worst of all to the urban hipster, boring in their simplicity.

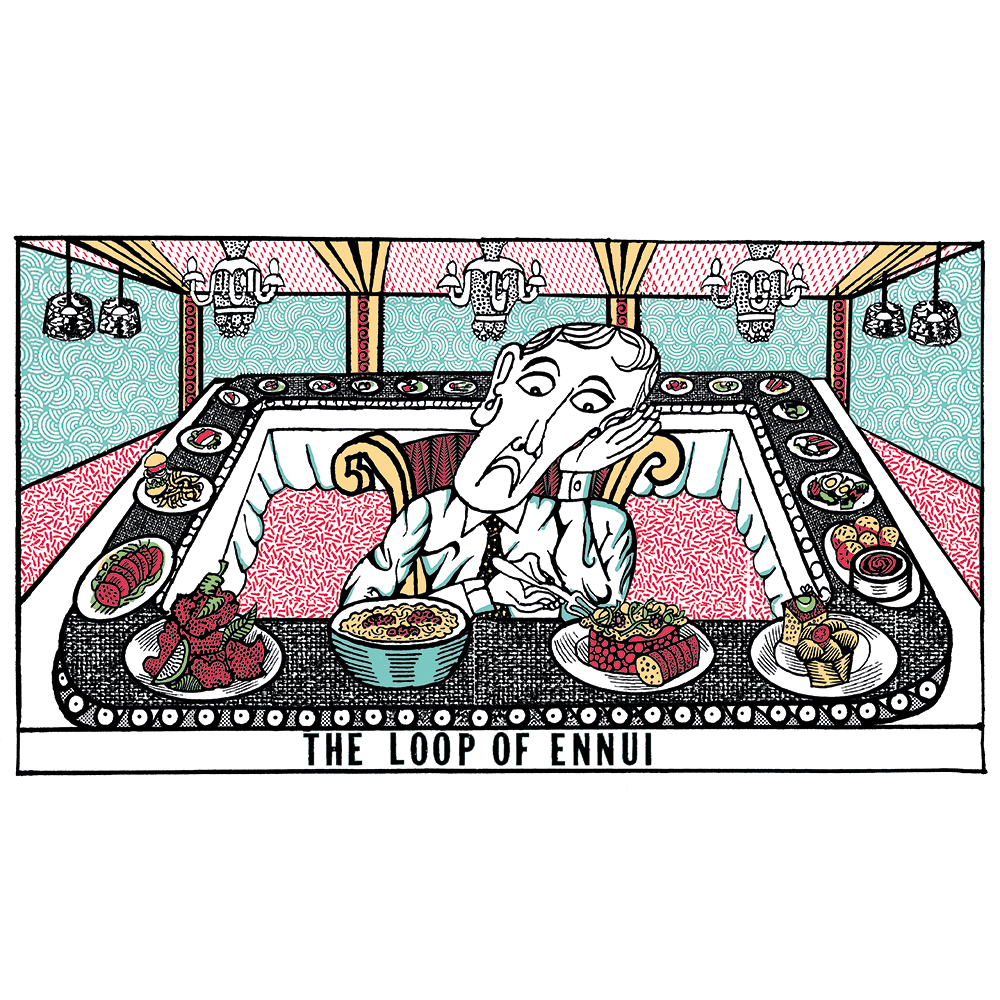

Instead, you get the consumerist ethos of more, more, more – a perpetually expanding matrix of flavors and ingredients that feels more beholden to the diversifying forces of the market than to the preferences of a refined palate.

Which is why these types of restaurants greatly appeal to a certain kind of rootless midwit, one probably not raised on haute cuisine, but now, having earned the right credentials and relocated to the right urban center, fancies himself a tastemaker – or in modern lingo, a “foodie.” He aspires to a life of truly cosmopolitan affluence but, stuck in the purgatory of middle- to upper-middle-class striving, he emulates sensibilities that feel “global” and “sophisticated.” With only a phantom idea of what those words even mean, he’s inevitably drawn to something somewhat familiar.

The result of his urban influence, which then trickles out to the periphery, is now the dominant model of the restaurant industry: elevated but approachably casual, exotic but still mostly recognizable, a little bit ironic and ultimately completely nondistinct.

A world that appears ‘diverse’ in its mosaic of faces and flags has become increasingly uniform in its cuisines

In trying to be inventive, these restaurants all wind up being the same. Far from being unique to chef or region, each menu is mostly interchangeable. Sure, a swordfish Reuben at Birmingham’s Bayonet sounds delectably unique – but in being so quirkily unpredictable, it fits in just about anywhere.

In this, we see a microcosm of globalism, but more saliently, its endgame. While globalists theoretically champion open markets, borders and cultural exchange in the name of an optimally diffuse multiculturalism, in practice, their program delivers total homogeneity. National economies are leveled under standardized consumerism; unique customs and traditions are sidelined by the culture of globalization itself.

Does America seem more diverse today, as a blend of global cultures has metastasized from coast to coast, or 50 years ago when each region was still largely beholden to its geography? A world that appears “diverse” in its mosaic of faces and flags has become increasingly uniform in its underlying systems, values, lifestyles – and clearly, cuisines.

The American restaurant industry is struggling: growth is down, costs are up, and consumers just aren’t eating out as much. Perhaps the answer doesn’t lie in catering further to the pretensions of a garish yuppie class and its twisted insecurities, but in giving the average American a comfortable, traditional and, above all, delicious reason to leave the house.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 27, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply