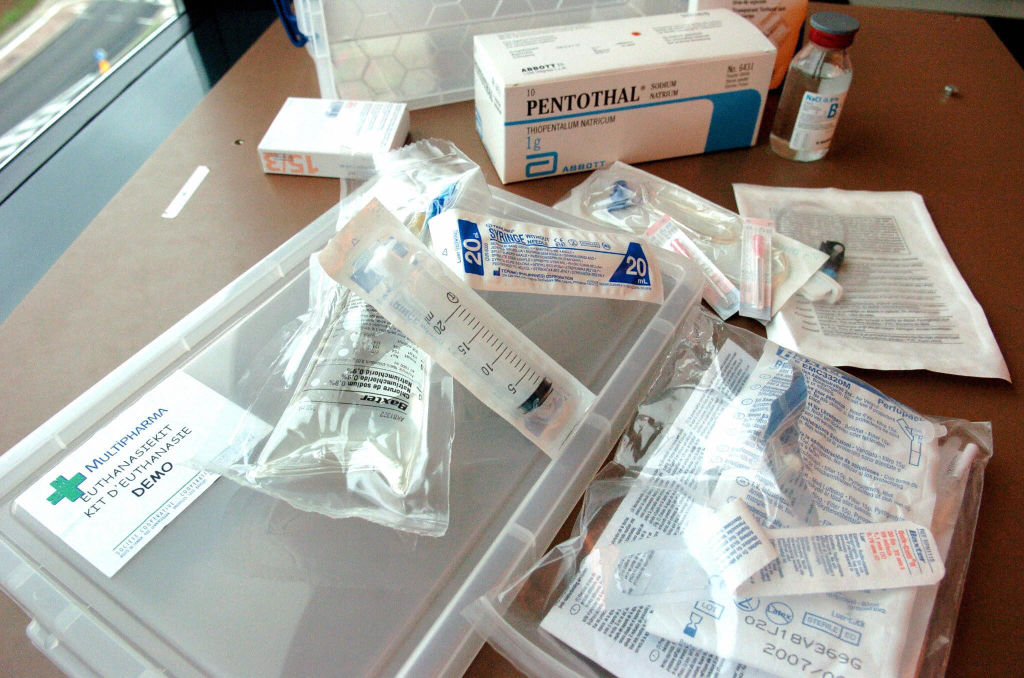

Death, somehow, seems like the wrong word. So Canada’s euthanasia doctors have adopted other terms for what they offer: each lethal injection is called a “provision.” Stefanie Green, a Vancouver Island doctor who used to work in maternity services, prefers “delivery.”

Canada has sleepwalked into a moral maze with no exit, where euthanasia becomes a solution for social problems

Since Canada’s parliament introduced euthanasia in 2016, a new vocabulary has arisen. Those with a terminal illness, whose death is “reasonably foreseeable” are “Track 1”; those who have no such diagnosis but qualify through “grievous and irremediable” conditions are “Track 2.” And assisted suicide has become, not merely “assisted dying,” but “Medical Assistance in Dying,” which some patients understandably believe means palliative care as opposed to lethal injection – and which is universally referred to with a jarring and faintly macabre acronym. If you want to die, you “ask for MAID.”

With such a large-scale outbreak of euphemism, you might speculate that people are trying to avoid thinking about some major injustice or terrible atrocity. And so they are. Canada has sleepwalked into a moral maze with no exit, in which euthanasia becomes a solution for its social problems. The homeless, the depressed, the poor, the chronically ill, those let down by the system or stuck on long waiting lists: all are at risk of finding themselves on Track 1 or Track 2.

Overall, one in 20 Canadian deaths comes at the hands of MAID, with a total of 60,000 between 2016 and 2023. The horror stories, at first shocking, have become almost routine. Roger Foley, a disabled man, was told by hospital staff that his care would cost $1,500 a day and did he want to discuss MAID? Sathya Dhara Kovac, who couldn’t afford home-care services wrote, before the assisted death she chose as a result, that “ultimately it was not a genetic disease that took me out, it was a system.” Rosina Kamis, who told the assessing doctors that her suffering was physical but confessed to her two dozen YouTube subscribers that her real motive was loneliness (“I think if more people cared about me, I might be able to handle the suffering.”)

Then there’s the woman whose only condition was a hip fracture and was dismayed at what her last decade might look like. The depressed man whose qualifying medical condition was a hearing problem and whose family claim he was effectively “put to death” under pressure from medical staff. The anonymized “Ms. B,” who had a chronic illness but whose request for MAID was motivated by housing problems. The many patients who have had doctors or nurses, entirely out of the blue, ask them if they have considered making an early exit.

Such stories make clear that MAID can be a substitute for care. Carla Qualtrough, a former disabilities minister in Canada’s Liberal party, remarked bluntly that in parts of the country “it’s easier to access MAID than it is to get a wheelchair.” Or, more generally, to die than to go on living.

Last November, when the British parliament first debated its own assisted suicide bill, the Substacker Rose Lyddon published a remarkably candid polemic against the proposal. Relating her long history of mental illness, she wrote: “When you’re deep in it, it’s very hard to argue against suicidal logic. The pros seem to vastly outnumber the cons. Living through each day is unbearably painful and you can see the pain and material damage you inflict on those who care for you. You’re a drain on state resources, the NHS has nothing to offer and considers you a nuisance who’d probably be better off dead, you lack the skills even to get dressed or feed yourself let alone change anything about your state of life. Loss of income and housing happens easily and it feels like nothing can stop the decline. It’s very difficult to feel hope or to attribute any value to your continued existence, which seems a net negative on every level. The only defence against going through with suicide is its not being on the table to start with.”

An assisted suicide law, Lyddon wrote, would shatter the taboo which puts suicide out of the question. “Enshrining a right to suicide in law will initiate a cultural shift that can never be undone.”

That single, decisive shift is still playing out in Canada. Almost half of those killed cite feeling like a burden as a reason for choosing MAID. An estimated 40 percent qualified for disability services. In one small-scale study, two-thirds of Track 2 applicants surveyed turned out to have a mental illness. The program has been denounced by the UN’s disability rights committee and described as “social murder” by Sonu Gaind, a professor of psychiatry at Toronto University. “Canada,” proclaims a headline in the Atlantic, that house journal of self-consciously reasonable liberals, “is killing itself.”

Once, it was possible to claim that a few troubling cases had been exaggerated into a trend by sensationalist newspapers. That notion was exploded by the journalist Alexander Raikin, who obtained recordings of MAID doctors conducting seminars among themselves. Repeatedly, the doctors discussed the regular cases of (as one put it) “people who would opt to die, because the social supports are so poor.” Chillingly, Raikin found that the doctors were unable to muster any real disquiet over their own role in the process.

Advocates for “assistance in dying” tend to operate on two settings. They present themselves as moral crusaders for “autonomy” and a “right to choose” which has been outrageously denied to those in serious suffering. But when pressed on the unintended consequences of this new “right,” they switch quickly from passionate advocacy to stonewalling (“That will never happen”) and handwaving (“That’s what the safeguards are for”).

So in 2015, when Canada’s Supreme Court ruled in favor of assisted suicide, the judgment dismissed concerns: assisted dying was for “limited and exceptional circumstances,” and there was no evidence from abroad of “a disproportionate impact…on socially vulnerable groups.”

In response, Canada’s parliament passed a law limited to those facing a “reasonably foreseeable” death; but in 2019, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the law would have to expand to cover grave but non-terminal illness. “People would be evolving as a society,” Trudeau explained, in another example of the mutant language which has provided the voiceover to Canada’s death march; but nobody should fear being pressurised into MAID “because you’re not getting the supports and cares [sic] that you actually need.” Of course not.

The emptiness of these assurances should come as no surprise. Advocates for euthanasia and assisted suicide always proclaim the importance of safeguards and strict criteria, but they can rarely outline a coherent case for why the righteous cause of “autonomy” should suddenly be cordoned off – why, say, those who are suffering but have no terminal diagnosis should have their requests refused. There will always be hard cases just beyond the cordon: the expansion of the law became near-inevitable after a legal challenge in Quebec, where a paralysed man asked for the right to die.

Such is the forward momentum of assisted suicide and euthanasia laws. After a few years, the politicians who insisted on “safeguards” have begun to forget why they were ever so squeamish. Isn’t this a legal right? Didn’t we all agree that denying people the freedom to choose is regressive?

Likewise, the requirements for strict monitoring come, in a short space of time, to seem pointlessly burdensome. A Freedom of Information request by the BC Catholic newspaper uncovered 2,833 paperwork errors in British Columbia in a single year – more than the total number of assisted deaths in the province.

After a few years the politicians who insisted on ‘safeguards’ have begun to forget why they were ever so squeamish

These errors are not merely procedural. Christopher Lyon, a Canadian academic, discovered in 2021 that his father – who had a long history of suicidality – was scheduled for an assisted death in two days’ time. He had been classed as terminally ill on the grounds that he had an elevated white blood cell count which (in Lyon’s words) “might be an infection that, if untreated, might become lethal, despite being a common side effect of his arthritis medication.”

Lyon pressed for a psychiatric assessment, which was granted but came back “full of errors”: it claimed, for instance, that there was no evidence of his father being depressed, although antidepressants were listed among his medications. After his father went through with the assisted death – “the worst day of my life” – Lyon pressed for an investigation. But the local health authorities blocked it.

The system, in short, has an institutional bias toward MAID. Doctors “are expected to facilitate access to death,” according to a joint statement from five senior academics and palliative care specialists, even if they know that the applicant hasn’t been offered “reasonable options” that might help to alleviate their suffering. Those who point to the abuse and neglect of safeguards are “dismissed as being “anti-MAID’” or accused of blocking patients’ autonomy.

Even now, Canada finds itself traveling toward new horizons. In 2027, the government plans to introduce MAID for those whose suffering is purely psychological. A parliamentary committee has also called for under-18s to be granted eligibility. And, as the Atlantic reports, everyday Canadian life increasingly incorporates this new culture of death. There’s an app to help you design rituals around your demise. There’s a podcast, Disrupting Death, where the hosts discuss “subjects such as normalizing the MAID process for children facing the death of an adult in their life – a pajama party at a funeral home; painting a coffin in a schoolyard.”

Most notorious was the glossy advertising campaign by the fashion chain La Maison Simons, featuring a woman, Jennyfer Hatch, reveling in her last days and her impending MAID appointment. “Last breaths are sacred,” Hatch intoned over images of her enjoying a final bittersweet party with friends on the beach. “When I imagine my final days, I see music. I see the ocean. I see cheesecake.”

Only later did it emerge that Hatch, too, had turned to euthanasia because she was struggling to find treatment for her chronic illness. “If I’m not able to access healthcare,” she had told an interviewer, “am I then able to access death care?” The ad, it turned out, was a euphemism too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply