Nick Drake’s debut album Five Leaves Left (1969) had so much going for it. Supported by tasteful string arrangements and a cast of noteworthy musicians, Drake (1948-74) sang with a delicate croon that sounded like Chet Baker if he’d gone to Eton, and he played some of the finest acoustic guitar this side of Segovia. Joe Boyd, the impresario who’d launched Pink Floyd and Fairport Convention, produced the album, and it bore the imprimatur of Island Records, London’s hippest label.

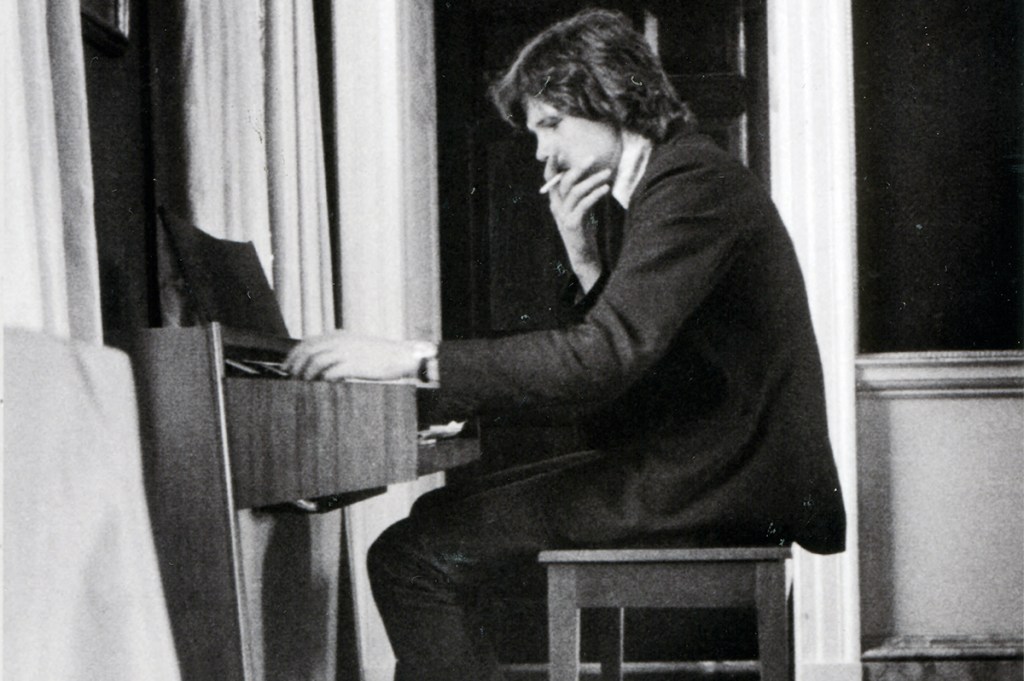

On the cover, Drake cut a shy but handsome figure, nonchalantly clad in blue jeans and blazer, gazing wistfully out the second-story window of an abandoned house in Wimbledon. Bordered in billiard-table green and with Drake’s name written in fancy cursive with the album’s title in London Underground-style sans serif, the cover evoked something patrician but bohemian-cool, well-traveled yet distinctly English, like a letter from a posh friend who’d followed the hippie trail to Afghanistan. The album hit record stores in July 1969, and Drake appeared headed for success. Instead, Five Leaves Left went straight to the remainder bin.

Drake cut a shy but handsome figure, nonchalantly clad in blue jeans and blazer

Two more fine albums followed, but success did not, and Drake died in 1974 from an antidepressants overdose, an obscure footnote to the British folk scene. For the next 25 years, a circle of family and friends kept the faith. Of all things, it was a 1999 Volkswagen commercial’s inclusion of his song “Pink Moon” that finally vaulted his music to the fame it deserved. His records have now sold in the millions.

Hagiographies of Drake long tended to fixate on his misery. This has not been entirely fair to the man. After Richard Morton Jack’s definitive authorized biography in 2023, our understanding began to change. Now, a landmark box set, The Making of Five Leaves Left, the first comprehensive repackaging of any of Drake’s albums, does justice to the musician, bringing his life and methods into focus and documenting his explosive creativity.

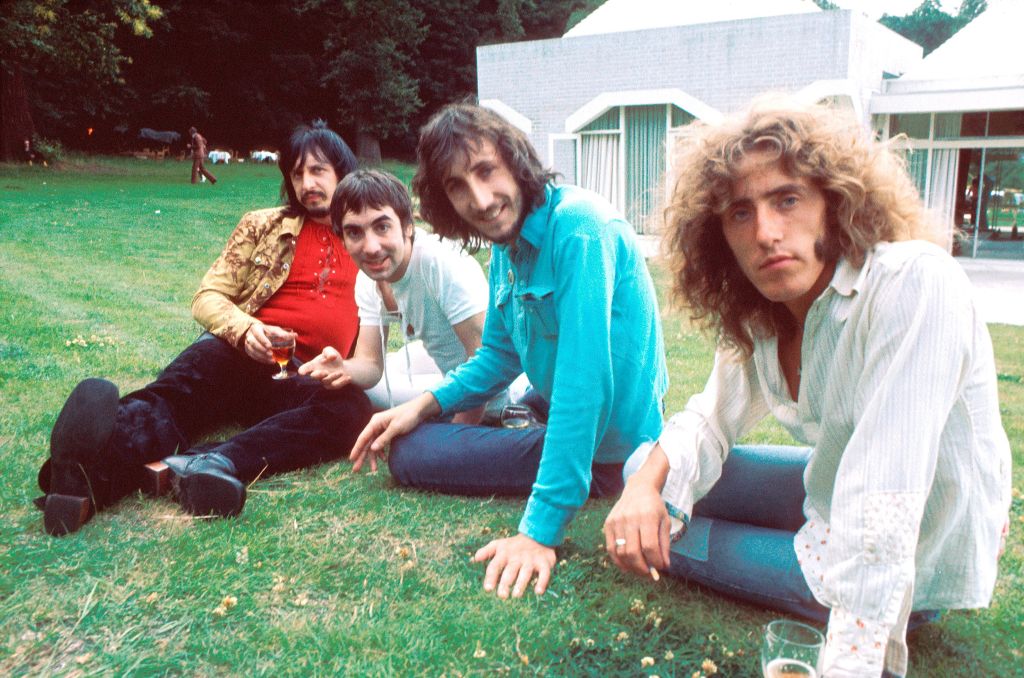

In Morton Jack and Neil Storey’s detailed liner notes, a new figure emerges: energetic, keen, hopeful. Five Leaves Left was a collegiate endeavor, dreamed up in Cambridge University bedrooms while Drake hopped to London and back between classes. As a 19-year-old freshman, he summoned the courage to play at London’s Roundhouse in December 1967, where he caught the eye of Fairport Convention’s bassist, who called in Joe Boyd.

Boyd, to his immense credit, saw no reason to rush Drake’s music. Disc one begins with their first studio session in March 1968. We hear the vaudevillian outtake “Mayfair,” and then guitar-and-voice run-throughs of various songs. Drake’s talent is close to fully formed, but it calls out for accompaniment. The box set homes in on the drastic evolution of the elegiac “Day is Done” to demonstrate the yearlong sweep of the sessions. We first hear an April 1968 attempt, for which Boyd brought in Richard Hewson, a professional arranger soon to work with the Beatles. The magic is absent: the tempo plods, and Hewson’s “Eleanor Rigby”-esque charts are too busy.

Drake and Boyd then went back to the drawing board for a November 1968 session sans orchestra. This was Drake’s first meeting with a crucial collaborator, the double-bassist Danny Thompson. Thompson immediately tuned in to Drake’s wavelength, flowing in and out of his vocal lines and adding a jazzy flavor to the music. The final piece of the puzzle arrived when Drake suggested they invite his 20-year-old schoolmate Robert Kirby as an arranger. Drake and Kirby had spent months in their Cambridge rooms with guitar, pen and paper, sketching out orchestrations for Drake’s songs, and had assayed them live at university events. Disc two of the set draws from a newly discovered tape from Cambridge, giving us unprecedented insight into their working process. On an April 1969 session we hear the payoff: Kirby’s simple string quartet blends perfectly with Drake’s soft vocals, branching off into countermelodies that spring organically from Drake’s polyphonic guitar style.

Though the newcomer would be better served buying the standalone LP, Drake fanatics will find The Making of Five Leaves Left revelatory. It’s a pleasure to revisit the finished album in remastered sound quality on disc four, reading along with the booklet, which reproduces the surviving manuscripts of Drake’s lyrics.

Take the haunting “Three Hours,” which, we read, Drake first played to his friends among the rows of war dead in Cambridge’s American Cemetery:

Three hours from sundown

Jeremy flies

Hoping to keep

The sun from his eyes

East from the city

And down to the cave

In search of a master

In search of a slave

Three hours from London

Giacomo’s free

Taking his woes

Down to the sea…

Drake, like T.S. Eliot, places his vaguely urbane characters in a landscape where the cosmological clashes with the quotidian. Formal and austere, his lyrics rise above the 1960s’ subpar songwriting, bogged down as it was in loopy psychedelic symbolism, Bob Dylan imitations, and political sloganism. Only “Fruit Tree” has something explicit to say:

Fame is but a fruit tree

So very unsound

It can never flourish

’Til its stock is in the ground

So men of fame

Can never find a way

’Til time has flown

Far from their dying day.

He was, perhaps, prepared from the very beginning for what might happen.

Drake’s story, like the stories of all artists unjustly neglected in their time, touches some chord within us. Perhaps it’s because we like to reassure ourselves of our good taste, that we would have known better than the benighted masses. Or perhaps it’s something deeper: we know that to be remembered is the closest thing to immortality this side of paradise. “Fame,” etymologically speaking, just means to be talked about.

To listen to Drake is to answer the old riddle about the tree falling in the woods with no one around: it does make a sound, even if it takes half a century for people to hear it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 29, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply