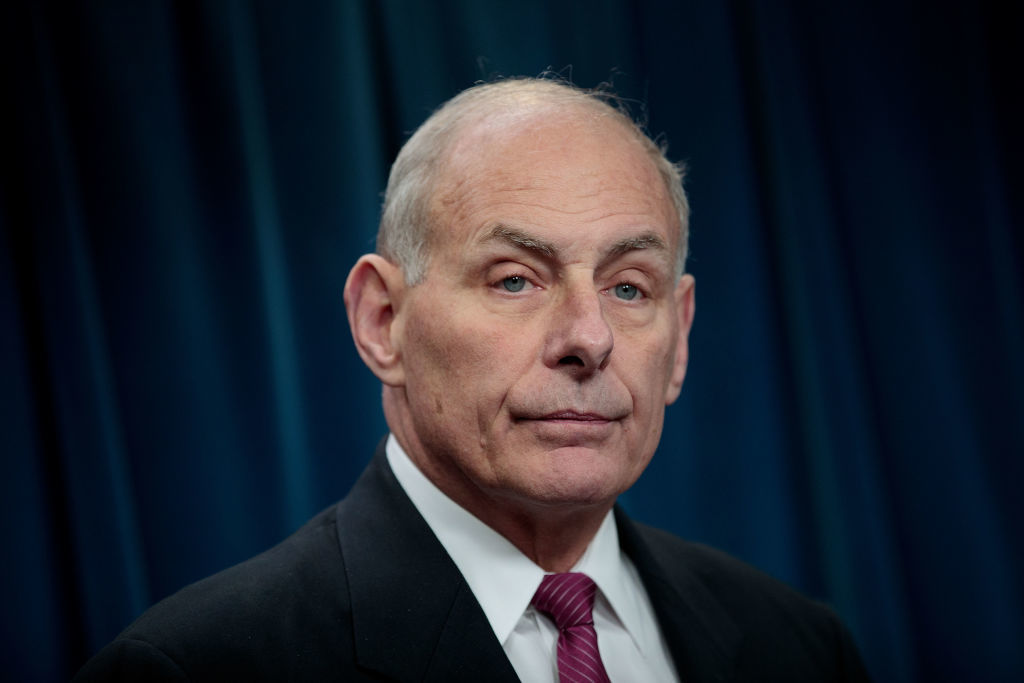

The John Kelly era in the Trump White House is drawing to a close. No one expects the chief of staff to hang on much longer, though if Rex Tillerson’s protracted exit from the State Department is any kind of precedent, Kelly may linger for weeks, even months. The end is in sight nonetheless: tales abound of the president circumventing his chief of staff to talk to people Kelly has banned from the Oval Office. The president evidently feels hemmed in by Kelly, who in turn, according to recent leaks, thinks the president is “an idiot” and “unhinged.” Kelly denies using those words. Even if Trump believes him, though, the fact that other people think the chief of staff described the president that way is damaging enough. Trump has little reason to keep Kelly on.

Kelly was supposed to bring the discipline of the Marine Corps general that he is to the White House. But even a chief of staff who is a Marine depends entirely on the president for his authority. What Trump has done by defying Kelly’s attempts to instil order is not to humiliate a particular chief of staff—though that might be the collateral damage—but to demolish the entire idea of the chief of staff as an office, along with the notion that the White House must be run like a cold, efficient, impersonal bureaucracy. No one else will do any better than Kelly has done. And that’s the way it should be.

Trump is president because he exposed the entire professional apparatus of the modern political party as so much painted plywood: the consultants, the PACs—remember Jeb Bush’s record-shattering superPAC fundraising in 2015?—and most of all the career politicians themselves. Trump went up against the very best the Republican Party had: Jeb, the best of the Bushes; the well-oiled conservatism of Ted Cruz; the endlessly hyped youthful cool of Marco Rubio. Scott Walker, an asterisk in the end, was a successful government-slashing governor hailed by Republican pundits as a hero from the heartland. Trump eviscerated them all, crossing movement conservatism’s red lines dozens of times along the way. He said nice things about Planned Parenthood and Medicare. He denounced the Bush family as warmongers in a Southern primary, no less. He thumbed his nose at John McCain’s record as a POW. And he won.

Then he won again against Hillary Clinton, retroactively said to have been a lousy candidate, when she had been the most popular politician in America right after Barack Obama’s re-election. Trump was as disruptive to party politics and conventional campaigning as iTunes and music streaming were to the recording industry. And throughout his first fifteen months as president, he’s been almost as disruptive to executive branch. He’s left positions unfilled, yet the world hasn’t stopped turning. His first major legislative efforts, multiple attempts to repeal Obamacare, were abject failures, yet he ended last year with a tax-cut triumph, as if legislative setbacks really don’t matter in the end. He has not infrequently substituted Twitter insults for sly diplomacy of the mandarin kind, with the result that he might actually end the 65-year Korean War and rein in the atomic mischief of Kim Jong-un. Why shouldn’t he fire his chief of staff? Why shouldn’t he fire everyone?

This is an exaggeration, to be sure: the U.S. executive branch and even the White House have carried on as ever, for the most part, Trump or no Trump. He has not done to the machinery of government what he did to the mirage of political professionalism. But he has called into question certain longstanding, unexamined beliefs about that machinery and its inviolability.

Would Trump without John Kelly be any different from Trump with John Kelly? Would Trump without a chief of staff be any different from Trump with a chief of staff? In fact, there would be differences—but how great would they be? We’ll know soon enough just what Kelly’s competence, or his reputation for it, really meant. In the meantime, it’s worth remembering that the chief of staff— the office, that is, not this particular man—did not exist until the middle of the 20th century. There were other ways to run an administration before that, and there will be other ways to run one in the future. Here, as in so many other places, Trump has shown Americans that not everything that seems important truly is.