Oh, to be a 19th-century Parisienne! A creature like no other, she arose “like Venus from the waters of the Seine,” as one fanciful journalist put it, “the supreme fruit of civilization.” An elegant arbiter of taste, she could be seen attending plays, concerts and exhibitions, or walking along Haussmann’s airy boulevards. By the time of the Third Republic, she did not need blue blood, so long as she had thoughts on paintings, poetry and music. To a city recovering from the horrors of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, which left thousands dead and monuments ravaged, she was a symbol of a brighter future.

Artists flocked to paint the Parisienne (and expat wannabes), who in turn welcomed the opportunity to commission status-boosting likenesses. By the late 1860s, portraiture was gaining respect in France as a serious genre. The boldest painters freely combined neoclassical portrait conventions with aspects of the avant-garde Realist movement (and, later, Impressionism), but it was a delicate game for both artist and patron. A dull portrait was just that, but take too many risks, and the sitter might appear vulgar or attention-seeking, the ultimate faux-pas.

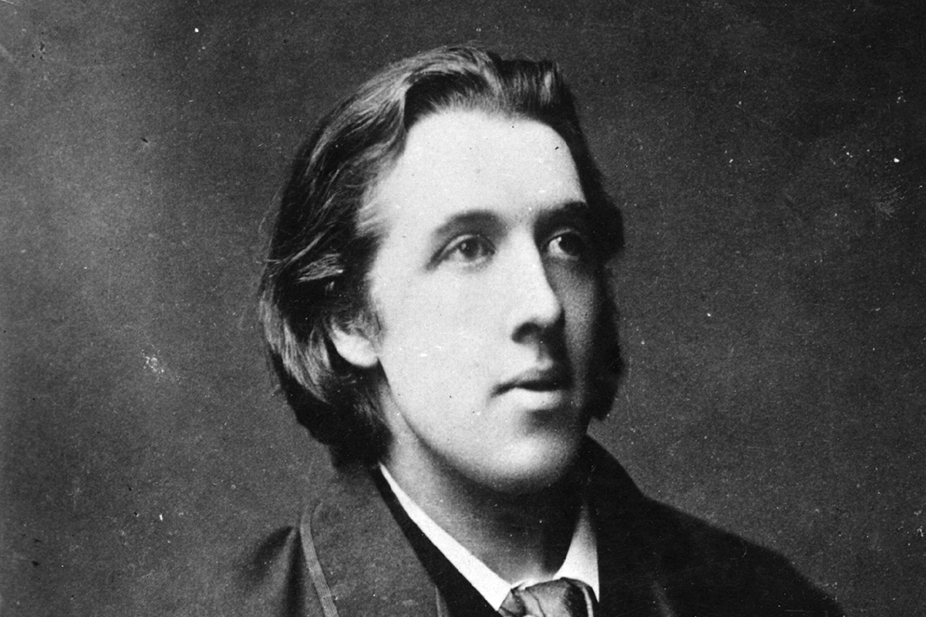

Enter John Singer Sargent, the painter Henry James described as “cultivated to his fingertips.” Who better to capture the Parisienne’s charms? The ultimate cosmopolitan, he was born to American parents in Florence and raised all over Europe. In 1874, aged 18, he settled in Paris to train at the studio of portraitist Carolus-Duran, and later at the competitive École des Beaux-Arts. A prodigious draughtsman and colorist, he was also well-read, fluent in four languages, a gifted pianist and, above all, très discret. He could entertain and impress his sophisticated female subjects between sittings, without worrying their husbands.

But he was nobody’s court painter. A visionary, he sought beauty in the strange, the exotic and the extreme – his childhood friend Vernon Lee noted his preference for “the bizarre and outlandish” – more than any patron’s approval. Before claiming his spot as a modern old master, he was bound to end up in hot water.

“Sargent and Paris,” an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum that soon travels to the Musée d’Orsay, accompanied by a book of essays, tells the fascinating story of his swift rise to the top of the French art world to his blazing exit ten years later, when he moved to London in the heat of a scandal ignited by the display of Madame X at the 1884 Paris Salon – a highly criticized portrait of the preening socialite Virginie Gautreau, dressed in a revealing black gown with a single jeweled strap falling off her shoulder. Displaying around 100 works from the first decade of his career, including dozens of early landscapes and travel scenes, the exhibition proves that the “curious intentions and strange refinement” one perplexed art critic saw in Madame X should really have come as no surprise at all.

Take his oil sketch (c. 1879) of an orchestra rehearsing at the Cirque d’Hiver indoor amphitheater. The conductor, Jules-Étienne Pasdeloup, was known for his adventurous programs that championed modern composers such as Gabriel Fauré. Sargent’s experimental painting is equally adventurous, with bold cropping and a peculiar vantage point from the upper seats. With abbreviated brushstrokes, he shows the players, instruments and sheet music disintegrating into abstract shapes as they are swept into the curves of the amphitheater. Three whimsically dressed circus clowns appear in the foreground, one turning his head in profile, revealing a face covered in white makeup with a smear of red paint across his mouth.

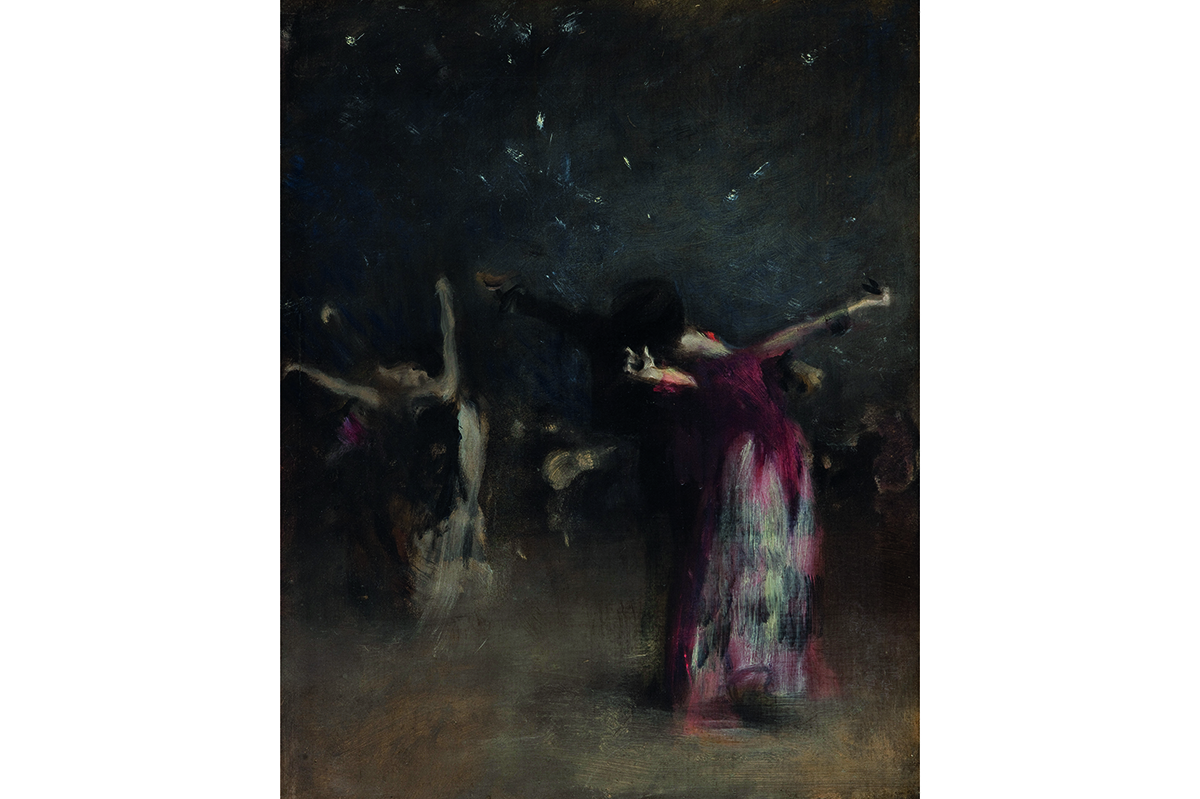

“Strange refinements” abound in his travel paintings, too. We see a study of the head and neck of Rosina Ferrara, his favorite model in Capri, shown in profile with a resolute stare, like the face on a medallion or cameo, or an illustration in an ethnographic study. She reappears in Among the Olive Trees – Capri (1879), standing in a complex pose in a field with her back to the viewer and head turned to the right, her arms intertwined around the branches of an olive tree. In The Spanish Dance (c. 1879–82), an evocative nighttime scene, two female dancers perform deep backbends with their arms raised and faces obscured, while a third leans forward, twisting to reach one arm to the ground.

His early portraits are similarly daring. In his 1879 painting of the red-haired Marie Buloz Pailleron, he places her in a windswept park, combining the genres of landscape and portraiture while using loose, Impressionist-style brushwork and light colors. The dramatic red-on-red composition of Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881) is just as radical, capturing the eminent surgeon and art collector Samuel Jean de Pozzi not in a professional setting, but rather an informal, domestic one. The doctor sports a bright red robe and stands amongst red velvet curtains and a red carpet, redolent of paintings of Catholic cardinals (or indeed Jonathan Yeo’s 2024 portrait of King Charles).

Dr. Pozzi, interestingly enough, was rumored to have been the lover of the aforementioned Virginie Gautreau, née Avegno. Born to French Créole parents in New Orleans, her mother came from a family of rich plantation owners, while her father, a Confederate general, died from wounds sustained during the Civil War. In 1867, aged eight, she was whisked away to Paris by her mother, who hatched a plan for her to enter high society. It worked, sort of: in 1878, a 19-year-old Virginie married the much older businessman Pierre Gautreau, whose fortune came from importing guano fertilizer from Peru. But she struggled to shake off her origins and be accepted as a true Parisienne.

The city’s papers chronicled her active social life and highly cultivated appearance, labeling her a “professional beauty,” but also an “American.” According to art critic Theodore Child, she “carried to unparalleled perfection the art of maquillage, enamelling, and of eccentricity in costume and coiffure.” Her efforts at self-fashioning earned both admiration and ridicule; the Russian emigré painter Marie Bashkirtseff confessed in her diaries that she looked “horrible in daylight because she uses too much makeup . . . but at night she is truly very beautiful.”

Sargent, for one, was enamored. He produced more studies of Gautreau than he did for any other portrait. We see pencil sketches capturing her unusual profile, which featured a long, upward-swooping nose and artificially lined eyebrows. In letters, Sargent expressed his delight and frustration in trying to record her “unpaintable beauty,” including the peculiar “lavender or chlorate-of-potash-lozenge” color of her made-up skin.

Both artist and subject were thrilled with the final picture, with Gautreau declaring it a “masterpiece.” Neither expected a “great ruckus,” as one observer remembered. Though exhibited under the title Madame ***, to preserve her anonymity, Gautreau’s profile and red hair were easily identifiable by Salon-goers, and she was immediately ridiculed for her vanity. Not only was she accused of looking both artificial and decomposed, but also indecent, as if her dress were about to fall off. (Post-Salon, Sargent repainted her jeweled strap in its proper place.) Her contorted pose, meanwhile, seemed to suggestively echo that of the sirens carved into the legs of the wooden table beside her.

The controversy briefly scared off Sargent’s patrons and perhaps hastened his decision to move to London. But they soon came running back. Sargent, for his part, always stood by Madame X, his American Parisienne, now a crown jewel of the Met’s collection. When the artist sold it to the museum in 1916, he declared in a letter to the director, “I suppose it’s the best thing I’ve done.”

And what of Gautreau?

After her initial distress – she and her mother came to Sargent’s studio “bathed in tears” – she seems to have taken the incident in her stride. A couple of weeks after the opening of the Salon, she was spotted at the theater in a dress with “a bodice held on the shoulders by diamond bracelets.”

Leave a Reply