In January 1882, a still little known 27-year-old called Oscar Wilde began his year-long, coast-to-coast, 15,000-mile grueling lecture tour throughout America. The ostensible purpose was to publicise the US tour of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience, whose precious aesthete Bunthorne — ‘what a very singularly deep young man this deep young man must be!’ — was partly based on Wilde. The real motive was to advertise himself and become a celebrity while searching for his true sexual identity.

Victorian men had to hide their homosexuality, but Wilde found a way to flaunt his real feelings. Wearing a theatrical costume while behaving outrageously on stage, he used his ambiguous sexuality to provide entertainment. Marriage in 1884 and two sons with sissy names (Cyril and Vyvyan) as well as male lovers (Robbie Ross in 1886 and Lord Alfred Douglas in 1891) were still in the future. Wilde did not marry to ‘cure’ his homosexuality. He fell in love with an attractive woman, but discovered that his deepest erotic yearnings were for men.

Wilde was better known for his wit than for his arty-smarty lectures. His life was a long-running, one-man show, written by and starring himself. ‘I have nothing to declare but my genius,’ he said when he arrived at US Customs. He found the performance of the Atlantic ‘disappointing’ and would have preferred more turbulence. He also put down the orgasmic cataract of a famous beauty spot: ‘I was disappointed with Niagara. Every American bride is taken there and the sight of the stupendous waterfall must be one of the earliest, if not the keenest, disappointments in American married life.’

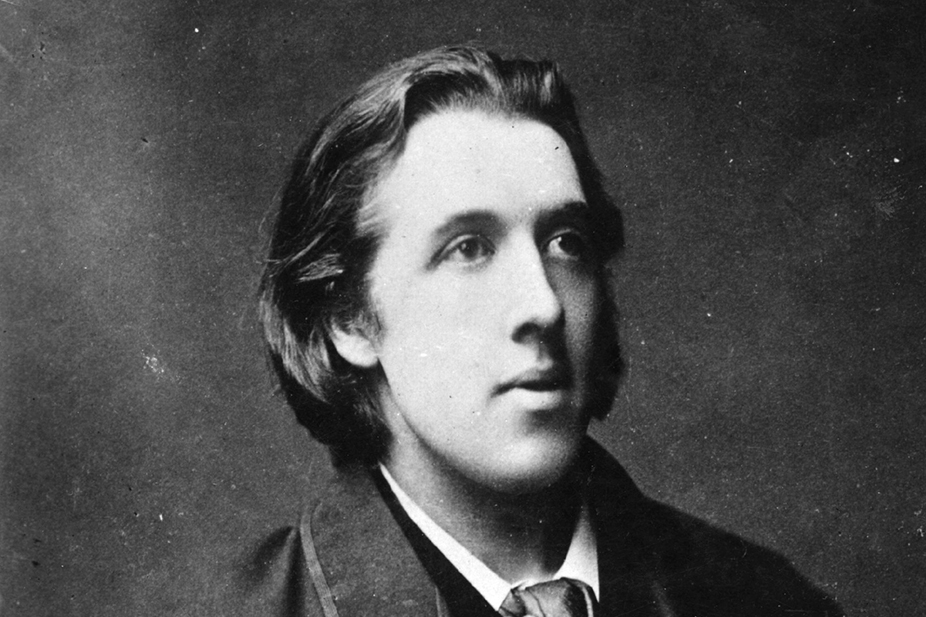

Wilde was 6’4, weighed a hefty 200 pounds, and had thick lips and a puffy face. His lectures mixed paradox and wit, eccentricity and nonsense, while spreading the war-cry of beauty amid the agonising ugliness of 19th-century American dress and décor. Wearing a long fur-trimmed green coat, wide Byronic collar, knee breeches, silk stockings and silver-buckled pumps, and waving a yellow handkerchief, the ‘queer, high-flavored fruit’ seemed defective in masculinity.

Wilde’s character was enigmatic, both appealing and appalling. He was Irish and English, an ass but clever, womanly and manly, aesthetic and athletic. He wore Buffalo Bill’s shoulder-length hair and, though arty, was a heavy drinker. He went down the mines with the bearded ruffians of Leadville, Colorado — ‘the roughest and most wicked town on earth’ — then supped on three courses of whiskey and was hailed as a hero, a man’s man and one of their own. Wilde’s repertoire of masks, his talent for self-fashioning and skill in re-inventing, transformed him into a media star. In this, he foreshadowed modern American writers whose flamboyant personalities attracted readers to their books: Hemingway, Mailer and the defiant homosexuals Gore Vidal and Truman Capote.

Michèle Mendelssohn’s Making Oscar Wilde is a lively and original examination of the mystery of Wilde’s identity. While trying to solve it, she found a new approach to biographical research, and material that was unavailable to previous life-writers. Vast online archives and databases provided a digital treasure house of local newspapers in the obscure towns where Wilde lectured. Her book includes 48 illuminating plates and shocking-pink endpapers. But the tiny-print, coarse-paper, tightly-bound book has narrow inside margins and is hard to hold open. It is also densely packed with facts and wobbly with digressions.

Mendelssohn belatedly states her theme on the last page: ‘His story is intertwined with the history of Anglo-American society as it grappled with massive waves of immigration, nationalist movements, racial and ethnic conflicts, political upheavals, new media technologies and a sensation-hungry press.’ Making the most of a hot issue in Wilde’s time and a trendy subject in our own, she connects him to the rabid racism in America in the years after Darwin’s Origin of the Species (1859) and the end of the Civil War. Waves of poor Irish immigrants were at the bottom of white society, and recently freed slaves were crushed beneath the Irish. The Irish Wilde, who travelled with a black servant he jokingly called ‘my slave’, was savagely caricatured by the hostile press. ‘The Wilde Man of Borneo’ was portrayed as an evolutionary throwback and primitive degenerate, a ‘negrofied Paddy’, closely related to monkeys and popular blackface shows.

The most interesting events of his tour were his crucial meetings with Walt Whitman in Camden, New Jersey, and with Henry James in Washington, DC. Whitman, a dandy and expert at self-promotion, had also created an attractive persona. But there was a great contrast in age and appearance between the precious fop and pretentious snob and the bearded and hearty man of the people. Since Wilde came to pay tribute and Whitman magnanimously accepted it, the two giant egos got on well. Praising the qualities in Whitman that were so different from his own, Wilde declared, ‘He is the grandest man I have ever seen, the simplest, most natural, and strongest character I have ever met in my life.’

In interviews about Whitman, Wilde talked about ancient Greek love, an idealised code for sex between men. Wilde later revealed that the poet had made no effort to conceal his homosexuality: ‘the kiss of Walt Whitman is still on my lips’. Like Whitman, he tried to tell the truth about himself when describing his own poetry as ‘the song of Sex, of Amativeness, and even Animality’.

While Whitman was warm and companionable with Wilde, James was frosty and hostile. James was repelled by Wilde’s costume, contemptuous of his self-promotion, critical of endless wandering and uneasy about his sexuality. He called Wilde ‘a fatuous fool’, a ‘tenth-rate cad’ and an ‘unclean beast’, and later satirised him as the restless aesthete Gabriel Nash in The Tragic Muse. Condemning Wilde, James condemned his own deepest desires.

Wilde was thrice the agent of his own destruction. He rashly filed a libel suit against the Marquess of Queensbury, father of Wilde’s idol, tormentor and nemesis, Lord Alfred Douglas. But Wilde did not realise that Queensbury had acquired damaging evidence to justify his accusation that Wilde was a ‘sodomite’. After losing this case, Wilde was prosecuted for the sexual crime of ‘gross indecency’. He then refused to flee to France to avoid arrest, and remained to face his punishment. Finally, he was provocative and aggressive, instead of charming and sympathetic, in court and was savagely sentenced to solitary confinement and two years’ hard labor.

‘The gods had given me almost everything.,’ he lamented. ‘I had genius, a distinguished name, high social position, brilliancy, intellectual daring.’ He had ‘lost wife, children, fame, honour, position, wealth’. As Samuel Johnson had written in his poem ‘The Vanity of Human Wishes’: ‘They mount, they shine, evaporate, and fall.’ In a series of spectacular transformations, Wilde has gone from obscurity, to fame as the leading British playwright, to notoriety and ruin, to an almost miraculous rehabilitation as a modern martyr and saint.

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL is a biographer and critic, and has published more than fifty books. His latest, Resurrections: Authors, Heroes — and a Spy is out this month.