When Donald Trump called on Iran’s Ayatollah to “surrender” during Israel’s recent war the word struck many as jarring – almost antiquated. No major global leader has used that language publicly since the unconditional surrenders of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in 1945.

But Trump’s invocation, intentional or not and soon abandoned by his call for a “ceasefire,” points to a deeper issue: Are the rules that governed mid-20th century warfare still relevant in the 21st century? Why has “surrender” disappeared from the language of modern warfare? And what, exactly, do today’s ever-growing humanitarian laws offer nation-states forced to operate under them, in a world that looks nothing like the one left smoldering in 1945?

To answer that, we need to revisit the hard truths at the end of World War II. The victors of that war – exhausted by two global conflicts in less than half a century – confronted a terrifying new reality. The atomic bomb had made traditional warfare obsolete. Total war was no longer a path to victory; it was a path to mutual destruction. The old goal – forcing your enemy to surrender – suddenly seemed reckless, even suicidal. At the same time, the scale of civilian and military casualties demanded a new moral response.

Specific but separate understandings, codified into law, addressed these dual concerns. Each was built upon assumptions that the global order was composed of sovereign nation-states locked in symmetric wars with clear distinctions between combatants and civilians.

The first concern – the prospect of total war in the nuclear age – was addressed in Article 33 of the UN Charter (1945). While it never explicitly mentions the term “ceasefire,” Article 33 enshrines the principle of peaceful conflict resolution, prioritizing diplomacy, negotiation and proportionality in warfare. Future wars, the Charter implied, should be defensive in nature and limited in scope.

The second concern – protecting civilians and combatants from grievous harm – was codified in the Geneva Conventions of 1949. These treaties established protections that became the foundation of international humanitarian law, aimed at limiting the cruelty of war and protecting those caught in its crossfire, that was enforced through institutions such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC).

But by the late 20th century – and unmistakably after the 9/11 attacks – the world had outgrown the assumptions behind these frameworks. The postwar rules governing warfare and civilian protection were never built for a 21st-century landscape shaped by jihadist insurgencies, transnational terror networks, narco-traffickers and other non-state actors.

Article 33 now serves to constrain nation-states rather than empower them, limiting their ability to end conflicts through decisive military means – even when faced with existential threats for which no negotiation is possible. Similarly, the Geneva Conventions’ emphasis on the civilian-combatant distinction falters in an era where that line is deliberately and strategically blurred by guerrilla fighters and terrorist organizations.

In short, the world these laws were written for no longer exists. Today democracies find themselves fighting enemies that do not abide by any conventions – legal, moral or strategic. In doing so, we are bound by a system that punishes our own restraint and rewards our enemies’ ruthlessness.

Institutions like the International Criminal Court (ICC) and International Court of Justice (ICJ) were built to uphold human rights and prosecute war crimes. But increasingly, they serve as constraints on legitimate military action by democracies.

The moral architecture intended to prevent a repeat of World War II has instead produced indecisive warfare – endless ceasefires, interminable negotiations going nowhere and strategic ambiguity. What it hasn’t done is produce peace.

No country has learned this lesson more bitterly than Israel. In every conflict with Hamas or Hezbollah, international pressure – not victory – ends the fighting. It is increasingly clear that the global threat environment has grown more perilous than at any point since the interwar period. Today’s “super-empowered” non-state actors – often backed by transnational funding streams and amplified by a credulous global media – continue to be perceived as far weaker than nation-states.

This perception dangerously underestimates their reach and ideological influence. Armed groups like Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon, despite controlling territory and launching deadly operations, are frequently recast as “freedom fighters” and victims within the framework of Progressive intersectionality.

But this is not just Israel’s problem. The Trump administration negotiated the Doha Agreement with the Taliban in 2020. But under President Biden, the agreement’s key provisions—negotiations with the Afghan government and a permanent ceasefire—were swiftly abandoned. Iran backs Hezbollah, Hamas, and other militias across the region while hiding behind its official status as a nation-state. Qatar shelters terror financiers while posing as a neutral mediator.

The postwar system was never equipped to handle actors like these. “Super-empowered” transnational networks – especially Islamist groups – do not fight for territory or recognition. They fight for ideology. Their ultimate goal is not compromise but conquest. For jihadist movements, the world is divided into Dar al-Islam (the House of Islam) and Dar al-Harb (the House of War). The endgame is global Islamic rule under sharia law – not a two-state solution.

These are not ragtag freedom fighters. They operate sophisticated propaganda operations, global fundraising arms, encrypted communications, and social media strategies. They exploit legal systems they do not recognize, media coverage they do not respect, and humanitarian protections they do not offer to others.

And yet the international community insists that liberal democracies adhere to outdated rules of engagement – rules that have been weaponized by their enemies.

This is not a call to abandon morality. But we must ask hard questions. Are the Geneva Conventions and Article 33 of the UN Charter still serving their intended function – to reduce the suffering of war and promote peace? Or are they now prolonging conflict by limiting the ability of responsible states to defeat those who reject every rule of civilized conduct?

If democracies are to survive and prevail in the 21st century, the rules of engagement must be urgently and honestly reexamined. A new global framework is needed – and America should lead the way.

Why Trump stopped calling on Iran to ‘surrender’

The Geneva Conventions now constrain legitimate military action

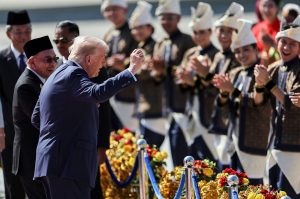

Donald Trump addresses the nation following the announcement that the US bombed nuclear sites in Iran (Getty)

When Donald Trump called on Iran’s Ayatollah to “surrender” during Israel’s recent war the word struck many as jarring – almost antiquated. No major global leader has used that language publicly since the unconditional surrenders of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in 1945.But Trump’s invocation, intentional or not and soon abandoned by his call for a “ceasefire,” points to a deeper issue: Are the rules that governed mid-20th century warfare still relevant in the 21st century? Why has “surrender” disappeared from the language of modern warfare? And what, exactly, do today’s ever-growing humanitarian laws offer…

Leave a Reply