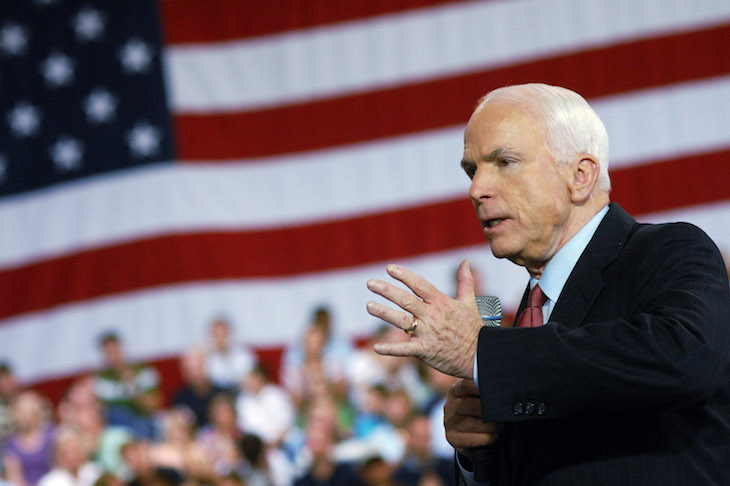

In every revolution there are revolutionaries who love the old regime even as they tear it down. John McCain was a symbol of that. He stood for masculinity, anger, honor, and pain to a generation of Americans — roughly speaking, the Baby Boomers — who have spent their lives treating such things as a pathology. John McCain was an unmedicated American. He was a totem of military strength to a post-Vietnam media and political elite that accepts war (of the humanitarian variety) but not warriors.

McCain the man is impossible to separate from his place in politics, and that’s a shame. As a man, he was brave. He was self-directed and defiant, traits that stood out in a gray Washington during his thirty years in the Senate. He was not a legislative giant, but he was a recognisable human being. If he was often an unpleasant one, sarcastic and short-tempered, that was part of what it meant to be flesh and blood in a town full of androids. He wasn’t governed by an algorithm: even I was surprised when he cast the decisive vote last year against a Republican plan to repeal Obamacare. It looked like he did so as much out of resentment as conviction — resentment that the party robots tried to insist he vote their way. You could cheer the man against the machine even if you didn’t like his politics. But there was a lot not to like.

He was born to Navy royalty, the son of an admiral. Yet that didn’t lead to a soft life: he flew in Vietnam and was shot down, then tortured for months by his captors. He came out maimed but unbroken, still a believer in the cause for which he fought, to such an extent that he favored fighting more wars like Vietnam. War was the defining theme of his public life and political career — whatever twists or turns he might take in domestic policy, he was almost always ready to see the country enter another conflict: with Iraq or Serbia in the 1990s, with Iraq again and Afghanistan in the early 2000s, with Libya and also Syria if he had had his way in this decade. Only in the last months of his life did he say — in his book The Restless Wave, published this Spring — that the 2003 Iraq War had been a mistake.

His brutal experiences at the hands of the North Vietnamese as a prisoner of war gave him moral authority when he spoke out against the use of torture by the United States, including waterboarding. But he stopped short of supporting legislation that would have ended that practice or other forms of what is euphemistically called ‘enhanced interrogation’. McCain’s support for the War on Terror simply outweighed his opposition to torture. And his admirers among neoconservative journalists paid no heed to his verbal objections.

McCain was the neoconservatives’ early favourite for the Republican presidential nomination in 2000, and not just on account of his foreign policy. He was seen as a reformer, someone who would move the GOP away from its fixation on smaller government (in reality, another mostly rhetorical commitment). ‘Instead of telling people that government is evil, McCain reminds them that public service is ‘‘the highest calling”’, David Brooks enthused in a 1999 Weekly Standard essay, which also lauded George W. Bush’s ‘compassionate conservatism’. McCain however was the second coming of Theodore Roosevelt, a leader who would mix militarism with a commitment to “national greatness” through strong government at home into a formula for restoring public virtue.

Then as now, liberals found this vision more to their liking than that of the real right wing of the Republican Party, with its emphasis on social conservatism and anti-government populism. In the mid-1990s, Bill Clinton toyed with the policy possibilities of school uniforms or mandating the installation of a ‘V-chip’ in televisions to censor violent programming. The dream of a morally activist but not socially conservative government conjured by writers like David Brooks may have helped stoke elite media enthusiasm for McCain’s candidacy. Certainly McCain’s accessibility to the media on his ‘Straight Talk Express’ bus tour bought him the personal esteem of much of the press.

McCain had a problem with the Republican right, however. Whatever reservations social conservatives and small-government types may have had about George W. Bush in 2000 melted away once the alternative seemed to be the senator from Arizona. Conservatives made Bush the Republican nominee that year, and the distrust in which they held McCain never went away. In a Fox News poll released two days before his death, McCain was viewed somewhat or strongly unfavourably by 47 percent of self-identified conservatives, with only 43 percent judging him somewhat or strongly favourably. Among liberals, 64 percent viewed him somewhat or strongly favourably.

Certain pundits have argued that McCain’s unpopularity among Republicans in the months before his death was Donald Trump’s fault. But even a decade ago, when McCain finally became the Republican presidential nominee, his right flank was vulnerable. McCain won fewer primaries and caucuses in 2008 than Trump won in 2016; fewer than any Republican nominee has won, in fact, in the past 40 years. In the 2008 general election, McCain’s advisors were so worried about his weakness with the GOP base and social conservatives in particular that they convinced him to pick Sarah Palin as his running mate. In the years after his loss to Barack Obama, the gulf between McCain and the GOP right only widened, as he joined the ‘Gang of Eight’ senators pushing to liberalise immigration law and made his mark in the first year of the Trump administration with his vote against Obamacare repeal.

What liberals saw as commendable maverick behaviour felt to grassroots conservatives like punching down: any time McCain deviated from party orthodoxy, it was to align with fashionable liberal opinion—from campaign-finance reform to immigration to his occasional outbursts against Christian conservatives, whose leaders he referred to as ‘agents of intolerance’. As cantankerous a character as McCain might be, his maverick instincts reliably put him on the side of establishment politics. The only orthodoxy he rebelled against was a minority viewpoint in Washington. He was a paradox: a spirited individual who bound himself to a stupefying consensus and enforced it against any dissent from the right. He was human, but he was on the side of the drones.

Taken as a man, John McCain had many virtues, as well as a few vices that might as well be virtues in an age that tends to the opposite extremes. If his temper was too hot, it was still preferable to the simulations of either hatred or passion that most politicians project. But as a politician himself, McCain was a maverick in all the wrong ways.