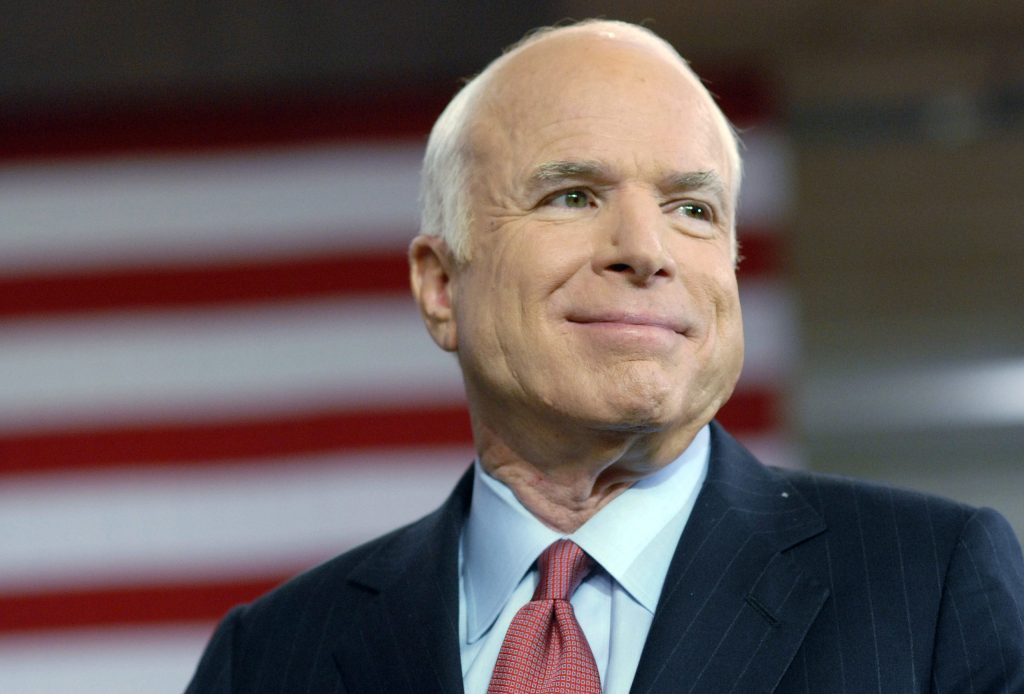

The centre of political gravity in the early 2000s moved comprehensively toward default, unrelenting hawkishness, but not necessarily because of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney. If liberals went along with the Bush/Cheney foreign policy project, it was often reluctantly and begrudgingly, out of a sense of duty — and in friction with their residual grief over a recent presidential election deemed stolen. The figure who instead inspired the genuine trust of liberals, and gave them confidence in the righteousness of America’s aggressive military path, was John McCain.

During that period, McCain played the role of nonpartisan statesman who ran against Bush, often viciously, and was therefore no natural fan, but nevertheless recognised the deep necessity of Bush’s muscular ‘leadership’ after September 11. His assurances made the hyper-interventionism of the day palatable to a critical mass of Democrats. Without McCain as a national soothsayer, urging Americans to set aside their differences and unite behind the Bush foreign policy agenda for the good of the world, the post-9/11 consensus might not have congealed as seamlessly as it did. (There was a reason McCain had the record of most appearances ever on Meet the Press — his function was wholly unique in terms of influencing public opinion.)

Since his death, it’s been tempting, and not entirely wrong, to describe the endlessly reverential homages to McCain as purely the product of his latter-day Trump antipathy. That’s undoubtedly a major factor; a dismaying percentage of Americans appear to believe that history began on November 8, 2016, and everything prior has been stricken from the record. But the roots of McCain’s sanctification go deeper, to the heart of the neoconservative project which ascended in the late 1990s and reached a grisly apotheosis in the subsequent decade. He might not have been the most sophisticated intellectualiser of their ideals, but in McCain the neoconservatives have lost maybe their truest avatar. And the national mourning upon his death — being led, notably, by liberals and Democrats — is yet another testimony to the unlikely perseverance of neoconservativism, even at a time when its most ardent proponents appear to have been exiled from the Republican Party.

As Matt Welch details in his book McCain: The Myth of a Maverick, the neoconservative media klatch headed by the likes of Weekly Standard founder Bill Kristol and his protegée David Brooks gravitated to McCain in the late 1990s, around when they began bemoaning a fundamental hollowness at the core of American conservatism. In a September 1997 joint op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, Kristol and Brooks diagnosed the malady: ‘What is missing from today’s conservatism,’ they lamented, ‘is the appeal to American greatness.’ Aside from the need for ‘moral assertiveness abroad,’ the rest of the tenets of their prescribed remedy were left purposely vague.

McCain stepped into the void. With his political malleability and soft contrarianism, he was a perfect fit for the neocons seeking to infuse the wayward Republican Party with a different kind of ideological energy. He lacked a consistent set of beliefs, it seemed, other than hazy instinctual Reaganism and an abiding belief in the inherent justness of American power. Welch recounts during this time, as he prepared for his first presidential run, McCain had frequent phone conversations with Kristol and began staffing up with advisers from the Weekly Standard orbit. His campaign credo was crafted in their image. While the neoconservatives later had no problem reconciling themselves to George W. Bush, Kristol said just this week that his vote for McCain (over Bush in 2000) was among the ‘proudest’ of his life.

McCain represented a newly ‘energetic’ conservatism, which would counterbalance the tendency’s more nihilistic, reactionary elements; integral to this was his capacity to attract liberals and Democrats. Eli Lake, himself a purveyor of the neoconservative ethos, recently hailed McCain as embodying ‘America’s Revolutionary Conscience’ — with ‘revolutionary’ not being a sentiment typically associated with traditional conservatism.

In the posthumous remembrances, the glowing appraisals from his Democratic colleagues is a reminder of the crucial conduit role that McCain played after 9/11 and since, with political ramifications much starker than simple ‘bipartisanship’ or ‘working across the aisle.’ It was in these trans-ideological alliances that McCain had the most consequential impact, as they were the vehicle through which his most overriding belief — in imposing ‘moral assertiveness abroad’ by way of American military force — was advanced.

On the floor of the Senate this week, for instance, Democrat Amy Klobuchar happily recalled their trip to Ukraine during a period of unrest in 2016; McCain was gifted a Ukrainian machine gun, while Klobuchar received only a pair of daggers. Klobuchar’s recollection took the form of a snappy, fond anecdote. (One of McCain’s talents was to reduce monumentally consequential political endeavours to platitudes and amusing stories.) Klobuchar endorsed what she characterised as McCain’s animating belief, which is that the United States has a ‘special responsibility to champion human rights in all places, for all peoples, and at all times.’ This, of course, is an airy way of dressing up a commitment to perpetual warfare all over the world, forever. But because of McCain’s aptitude for framing this project in terms Democrats could relate to — with a particular emphasis on the ‘human rights’ refrain — he has single-handedly kept alive a crucial cross-partisan link to sustain the neoconservative ideological mission. His deathbed denunciations of Vladimir Putin (and Trump’s perceived capitulations) continued in his final months to endear McCain to Democrats, and thereby maintain neoconservatism as a viable national political force (even if the term ‘neoconservatism’ is seldom invoked anymore.)

McCain might not himself represent the final death of neoconservatism, but he represents the demise of a vital link that neoconservatives have always desired: a means for reaching liberals, and forging the kinds of coalitions necessary to embark on major interventionist endeavours.

One should never discount the propensity of neoconservatism to bend itself and adapt to changing political circumstances; even Trump himself is not immune to its reach — especially through a cadre of advisers who have marinated for years in a Washington DC intellectual ferment where the neocons still have some measure of influence (John Bolton comes to mind.) But as far as an avatar who wholly and fully represents the peak of neoconservatism, and who was there, in a sense, at the ‘founding’ — and whose central conceit was appealing to non-conservatives in the name of promoting unified “American greatness” — as McCain goes, so goes all that.