“The publisher who writes is like a cow in a milk bar,” Arthur Koestler once declared. For some reason this put-down has never stopped publishers from fathering their memoirs, and the book trade titan’s life and times used to be as much a staple of the library shelf as slim volumes of nature poetry.

As in other branches of life-writing, the procedural approach tends to vary. There are practical primers – Stanley Unwin’s The Truth about Publishing, say, from the year of the general strike, or Anthony Blond’s The Publishing Game (1971); there are delightful vagaries in the style pioneered by Grant Richards’s Author Hunting (1934); and there is the emollient, if not absolutely vainglorious, reminiscence, most recently on display in Tom Maschler’s Publisher (2005).

That such books no longer seem to make it on to publishers’ lists has an economic explanation – they don’t sell and are essentially vanity projects – but also a structural underpinning. Here, in a more corporate age, the big beasts of old-style publishing, those legendary autodidacts and self-made bruisers who trampled on their competitors like so much chaff, are most of them gone. The days when Chatto & Windus’s Carmen Callil could run her firm at a loss that exceeded its annual turnover seem as remote as the Battle of Lepanto.

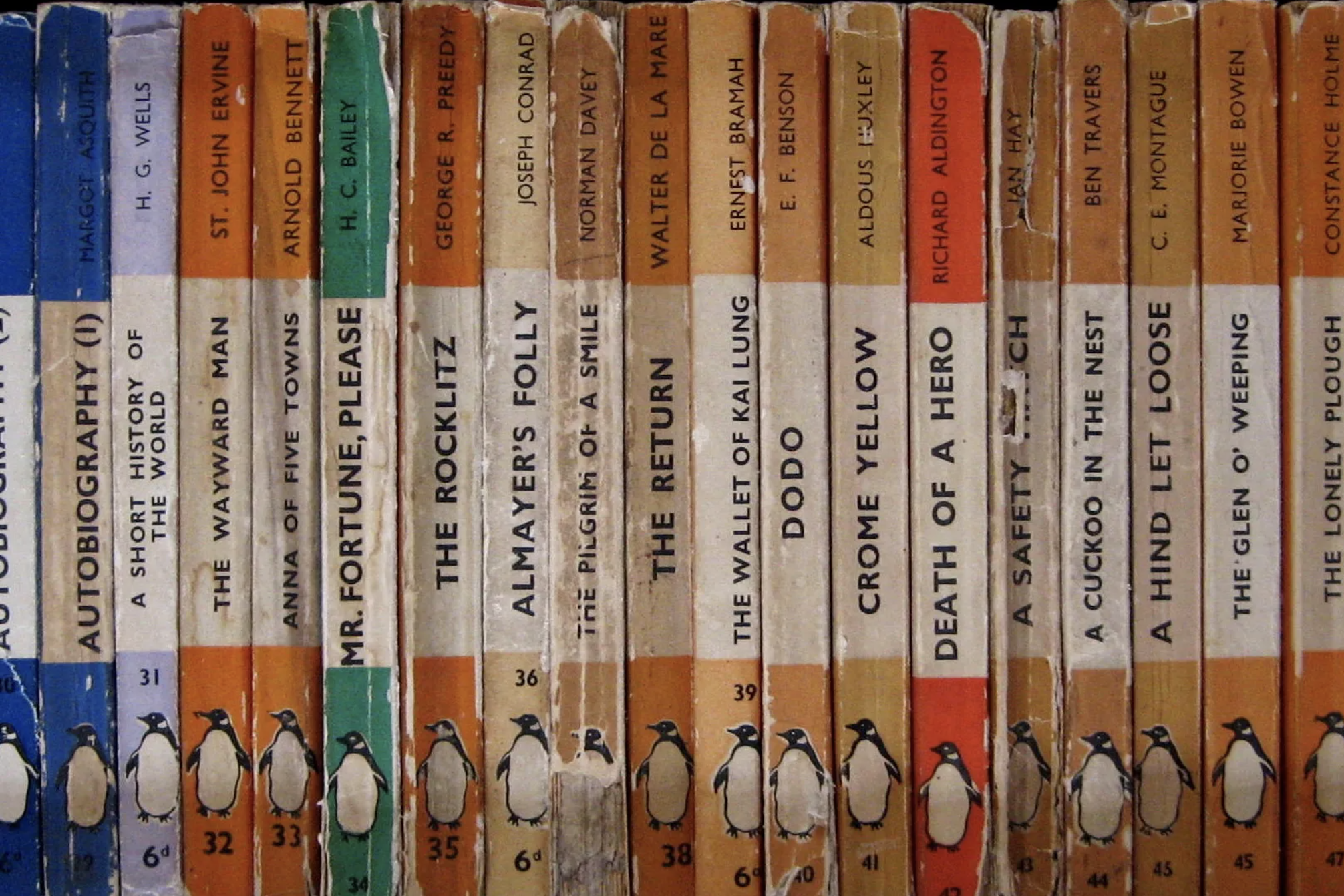

Anthony Cheetham, the author of this slim, reticent yet lavishly produced volume, is a major player. In fact a glance at the CV laid out in successive chapters of A Life in Fifty Books reveals that among the handful of survivors capable of writing a history of British publishing since the mid-1960s, he is the best qualified of all. From an apprenticeship in downmarket paperback houses such as the New English Library and Sphere Books to commanding roles at Random House and the Orion Publishing Group, Cheetham was well-nigh omnipresent. He sponsored the works of everybody from Donald Trump and Andrei Gromyko to Vikram Seth and ran into every book trade shark who fiddled a royalty rate or withheld an advance.

And what does Cheetham have to say about the cavalcade of bestselling authors and devious agents who passed through the various publishing houses where he ruled the roost? Well, Ben Okri, whose The Famished Road (1991) won the Booker Prize the day before Cheetham was sacked from Random House by its American hatchet man, is “a master artist who has devoted himself to all nine of the classical muses.” The late Irving “Swifty” Lazar, one of the most rapacious deal-brokers who ever extracted his 15 percent, was “a kind and generous soul;” while of Colleen McCullough, the author of the perennially bestselling The Thorn Birds (1977), Cheetham will say only that “her hospitality was as legendary as her writing.”

Even Robert Maxwell is remembered for his formidable intellect and lively sense of humor

None of which, sadly, tells us anything much about the personalities on display. Did Okri ever threaten to take his books elsewhere? Did McCullough, when not furnishing her publisher with high-end meals, ever turn nasty? These are the things that give publishers’ memoirs their zip, but Cheetham doesn’t seem interested in them at all. We are in slightly more promising territory with Kingsley Amis, whose alcoholically charged lunches once saw his companion sent home catatonic in a taxi. But no real dirt gets dished, and even Robert Maxwell is remembered for his formidable intellect and lively sense of humor.

The best bits of A Life in Fifty Books turn up in the early chapters. These take in a notably upmarket childhood in Vienna, where Cheetham’s father was a diplomat; Summerfields prep school (one of the 50 books of the title is Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring, devoured by torchlight beneath the bedsheets and an example of a work that left an indelible impression on Cheetham); and Eton, where he befriended Jonathan Aitken and, while staying at the latter’s Suffolk house, met half the Suez-era Tory cabinet and defeated the then foreign secretary Selwyn Lloyd at croquet.

The first few publishing years, too, have an elegiac crackle that some of the later material lacks. I was fascinated to learn, for example, that Cheetham was the only begetter of Timothy Lea’s Confessions of… franchise. On the other hand, a final chapter on “the future of publishing” consists of a couple of pages of bromides and a warning that “streamers are investing billions in new series because that’s where the money is made.”

I salute Cheetham for his persistence, his indefatigability and his lifelong habit of picking winners. I acknowledge that the British book trade would have been a much poorer place without him. But I respectfully suggest that this catalogue of his 81 years on the planet is an opportunity missed.

Leave a Reply