When Guillermo del Toro’s new film adaptation of Frankenstein makes its bloody advent on Netflix later this year, the backdrop for 19th-century body snatching and resurrection may look familiar to many viewers. It was shot last year on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile and images from the set suggest that, as ever with del Toro, this will be a hallucinatory and haunting exercise in Gothic extravagance. If so, he has picked the perfect city on which to unleash Frankenstein’s monster.

Edinburgh is a place that wears its long and often violent history like a velvet cloak. There is elegance abounding, especially in the Georgian New Town, yet its streets still hang heavy with menace, especially by night, when its cobbled wynds and vaguely threatening 19th-century apartments create an appropriate atmosphere for something unspeakable. If London is England’s swaggering, gin-soaked rake, Edinburgh is Scotland’s brooding laird, nursing both a dram and a grudge.

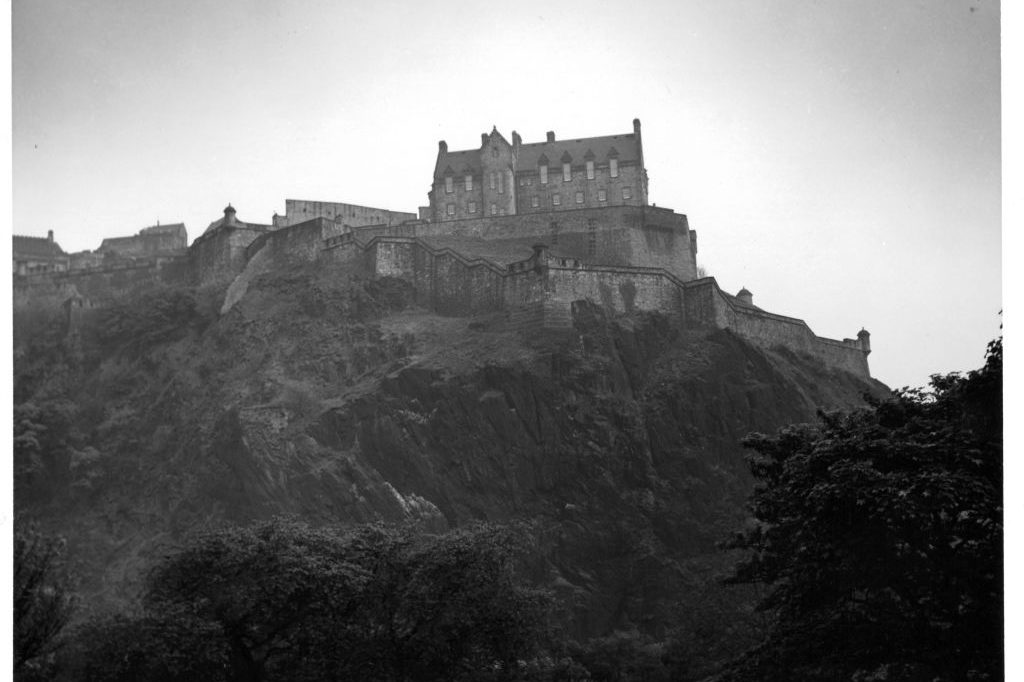

The Gothic spirit of Edinburgh begins, inevitably, with its famous castle. It hangs over the city, as tourists (not exclusively American) swarm its ramparts, snapping photos with selfie-sticks longer than a claymore and pronouncing its name incorrectly. (It’s “Edin-bruh,” not “Edin-bourgh.”) Nearby sits the Witchery, one of the most famous restaurants-with-rooms in Scotland – and one drenched in history.

I spent a night in the Sempill suite, which is decorated with leather-paneled walls and a four-poster bed so large that it had to be clambered into (a helpful, somehow hilarious, small stepladder is thoughtfully provided). Dinner at the nearby restaurant could only be seen by candlelight.

If London is England’s swaggering, gin-soaked rake, Edinburgh is Scotland’s brooding laird

Wandering down into the Grassmarket in the Old Town, where malefactors used to be hanged, a thick fog was hanging about the city. The past sits heavily around. Over there lurks the specter of Deacon Brodie, an upstanding citizen by day and lawless brigand by night. He was duly hanged, but his influence lives on in the pages of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which took the inspiration for the dual-personality plotline from Brodie’s nefarious antics. He also lives on in Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, whose eponymous heroine claims to be descended from the Deacon.

In another corner, the ghosts of Burke and Hare, that murderous pair of “resurrection men” – grave robbers – slink through the shadows, searching for corpses to sell. (I passed by a strip club named after them.)

Should one wish to commune with the spirits of the past, Edinburgh is the place to go. The graveyards – or kirkyards, as they are known – don’t feel like resting places, but rather stages for resurrectionist dramas, where the dead were once snatched from their graves to fuel the Enlightenment’s grim scientific curiosity. Even Greyfriars Bobby, the loyal Skye terrier immortalized in bronze, seems less a cuddly mascot than a spectral watchdog, his stone eyes glinting with reproach.

St. Giles’ Cathedral, with its crown spire piercing the heavens, is a Gothic masterpiece that somehow feels more pagan than pious – its gargoyles leer with an impudent mischief that its hellfire preacher John Knox would have condemned as Popish excess. Below ground are the city’s subterranean vaults, their damp walls whispering tales of plague victims and illicit trysts. Edinburgh’s beauty is inseparable from its decay; it is a city that revels in its own rot, polishing it to a macabre sheen.

Visitors here need more than bone-piercing chills – caused naturally by the weather, as North Sea winds whistle over from the Firth of Forth. Otherwise, a trip here would swiftly become overwhelming. The Edinburgh Fringe Festival, held every August, brings a welcome air of levity and vibrancy to the streets, helped by the (usual) advent of better weather. But the outskirts of the city bring their own delights, too.

I stayed in the Allan Ramsay suite at Prestonfield House, a hotel a couple of miles outside the center. The room isn’t named after a soccer manager as I’d first thought, but for the 18th-century Scottish portrait painter who came to prominence in the days of the Scottish Enlightenment.

The cooked breakfasts that begin the day are suitably vast – I’d never encountered “fruit pudding” before, a riot of suet and golden raisins. It is served up beside black pudding and haggis – and the hotel’s restaurant, Rhubarb, is rightly regarded as one of Edinburgh’s most distinguished spots. It’s peerless if you want to defrost from the chillier welcome of the city’s streets.

Shortly before I return to London, via the sophisticated comforts of the first-class railway carriage, I feel that I have to see parts of contemporary Edinburgh to reassure me that the Gothic grimness of the city can be offset with something more laid-back.

I find it at the Palmerston, the most talked-about spot anywhere in the center at the moment. It is, at different times of day, a buzzy café, a much-lauded bakery, a romantic restaurant and an intimate bar. Whatever your choice of entertainment, you will find it at the Palmerston. I sit at the bar to enjoy pickled herring with rhubarb, very fine lamb served with an excellent Cabernet Sauvignon and a couple of their unique takes on well-worn cocktails, including the “Sazerapp” – their version of a Sazerac – and a coffee Negroni. This drink takes the Negroni and Espresso Martini, two drinks usually on nodding terms at best, and fuses them.

A couple of hours here, and I’ve shaken off the sense that I’m a supporting player in some 18th-century tragedy, although my liver may well be ripe for dissection after the unholy melding of grape, grain, fish and animal that has made up my dinner.

Edinburgh’s truest secret? It may seem like a dour, foreboding place, fraught with menace and shadows. But just as Frankenstein is not just a horror novel, nor is a trip to Scotland’s most contradictory and beguiling city really that disconcerting. Underneath its gray, foreboding exterior, it is a joyful and exciting city. But don’t tell anyone; it has a hard-won reputation to maintain.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply