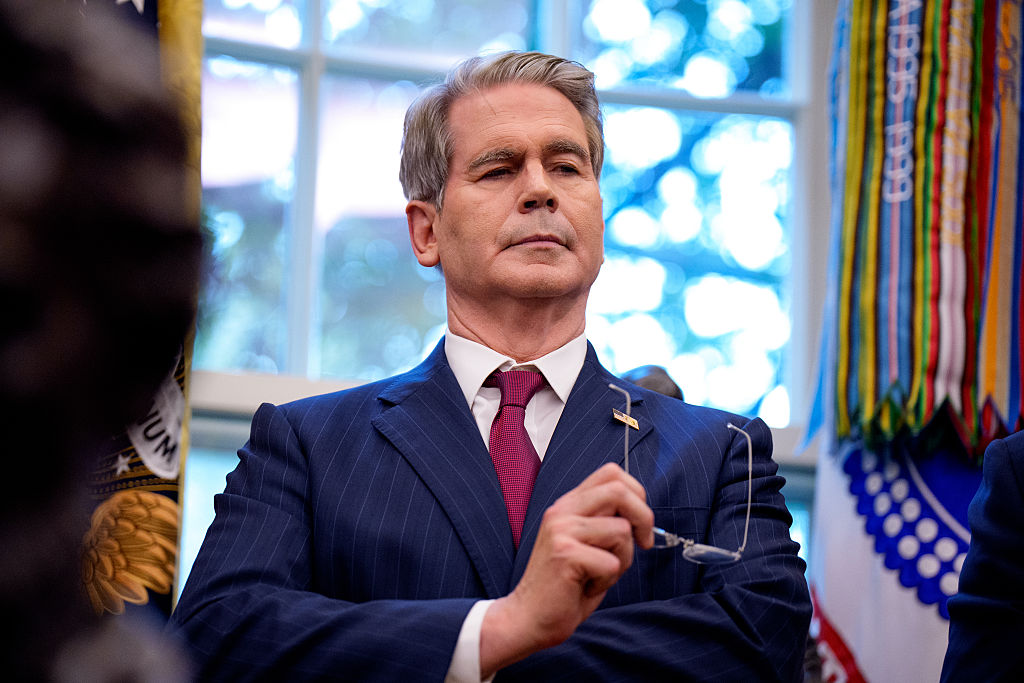

With Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent announcing that a trade deal between the US and India could be imminent, it once again raises the possibility that Trump’s intended outcome is not the imposition of high, permanent tariffs – but that the measures announced on “Liberation Day” were really just shock therapy aimed at the ultimate liberalization of trade.

It is significant that India was one of the countries which were originally put down for some of the higher tariffs: 26 percent was going to be the blanket rate on imports from India. South Korea, another country with which trade deal negotiations seem to be in an advanced state, was going to be subject to 25 percent tariffs. Given that the President has delayed the introduction of tariffs on countries other than China by 90 days, these rates are now unlikely ever to come into force.

Many might have assumed that if Trump was going to do any trade deals, he would start by rewarding the countries whose trade policies he sees as less of a threat to the US – those which, like the United Kingdom, he restricted to a 10 percent tariff. But a trade deal with the UK seems to be a lesser priority, much to the British government’s disappointment. There is, however, some logic in focusing on deals with India and South Korea: if you want to benefit US exporters, why not start with the countries where there is the most scope to increase exports?

If the Trump administration does start to announce trade deals, it will change the international global mood significantly. But it really should not come as a surprise if it becomes clear that Trump’s ultimate goal is the liberalization of trade. He did, after all, pursue the same line during his first presidency. He imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum imports to the US, threatened all-out trade war – and then turned up at the G7 summit and surprised fellow leaders by posing the question: “Why not go to zero tariffs?” They really didn’t have an answer.

An Indian trade deal is unlikely to go that far. Indeed, he would face great anger and disappointment among his political client base of blue-collar workers if the end result of all this was a rise in imports of steel and other goods from India. At the same time, India is not going to do a deal with the US unless it sees advantage for its own exporters; it is not going to accept clauses that impose 26 percent tariffs on its main exports, which include electronics, ores, and rice.

It would be rash to assume that the outcome of the past few weeks will necessarily be less free trade. It may turn out that the Trump-watchers who said that punitive tariffs were just a negotiating tool he was using as part of his negotiating armory were right all along.

Leave a Reply