The first thing revealed by the high and wide-ranging new tariffs President Trump announced on “Liberation Day” is just how limited other recent American presidents have been in their thinking. Their ambition was to get elected and re-elected, then retire comfortably into a tranquil post-presidency. They would finish their days lending their names to charities and writing their memoirs (or rather, commissioning ghostwriters to fulfill their publishing contracts).

The idea of destroying and remaking the global economic order never crossed their minds. But Trump is thinking bigger. He doesn’t want to go to his grave as just another has-been ex-president. He’s going to reshape America and the world – even literally, by redrawing US national boundaries and renaming international bodies of water.

His approach to economics is much like his approach to geography. The latter is reminiscent of 19th-century manifest destiny and the golden age of American territorial expansion. Trump’s tariffs hearken back to that era as well. The United States developed into an economic superpower over its first century and a half, an era in which tariffs were usually the federal government’s chief source of revenue and had the additional effect of shielding US industry from foreign competition. If it worked then, why not now?

This is one logical way to apply the slogan “Make America Great Again.” When America grew great the first time, it relied on tariffs. The second era of greatness will rely on them, too.

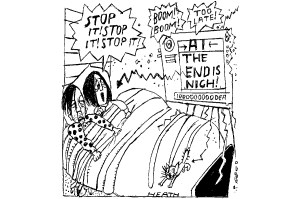

To orthodox economists this is pluperfect insanity. Unfortunately for them, their credibility with a public frustrated by the fruits of free trade is negligible. But it’s not their reputations that pose an obstacle to Trump. Their credibility may soon be restored if the public finds the price of Trump’s trade policy anywhere near as high as the economists expect. If anything could give moribund economic globalism a new lease on life, a disastrous attempt to establish an alternative by presidential fiat would be just the thing to do it.

That worries unorthodox economists who want the US to adopt stronger industrial policies but aren’t confident that omnibus tariffs are the best way to do it. Oren Cass and the National Association of Manufacturers have put their reservations on record. NAM framed theirs in a Trump-pleasing way, calling on Congress to pass an extension of the President’s tax cuts to help offset new burdens the tariffs might impose on American manufacturers, who are apt to need foreign components and raw materials at whatever tariff-augmented price they have to pay. Even industries that stand to gain from tariff protection can’t build factories overnight. With uncertainty about just how thorough the implementation of the tariffs will be and how long they might last – a Democratic Congress could repeal the authority behind them in two years’ time, or a panicked Republican Congress might do so sooner, to say nothing of what’s in store come 2028– manufacturers can’t treat either the new dispensation or the old status quo as solid ground on which to build their plans. Two radically different outcomes are possible, which is one reason other presidents didn’t dare try anything this bold.

The irony is that for all the enmity and reciprocal contempt the orthodox and unorthodox camps have for one another, both believe that economic practice must be guided by the right economic theory, while many “New Right” Trump supporters hold that only politics matters. The right instincts coupled with sufficient power are all that’s needed, with economics serving only as a kind of rhetoric – as salesmanship for the right, or wrong, political program. This part of the MAGA coalition is entirely enthusiastic about the tariffs, since nothing other than a deficiency of willpower could cause them to fail. As long as Republicans stand firm, a plunging stock market or rising supermarket prices won’t put the Democrats back into power. The tariffs are politically good for the working class, which in turn is essential for Republican electoral success. This is not a theory so much as an axiom.

In his first term, Trump was more of a reformist than a radical, a president who replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement with a US-Mexico-Canada agreement, the USMCA. But that Trump was content to be a president with a larger-than-life personality. The Trump of 2025 is aiming to be much more than that – he wants a larger presidency, or perhaps something larger than the presidency.

Yet that doesn’t mean he won’t modify or moderate the tariffs in exchange for concessions of various kinds from nations all over the world, or in response to pleas from American interests, including consumers. The orthodox economists who oppose tariffs on principle profess to find it inconsistent that Trump might like tariffs both for what they actually do and for what threatening them can bring about. But making good on the threats only adds to their power to leverage negotiations. Whatever discomfort the tariffs may cause at home, they’ll cause a great deal more abroad, and the President will be in a position to make demands of other nations on subjects ranging from immigration and fentanyl to NATO spending and cooperation with Trump’s initiatives in foreign policy. And Trump can call off the trade war, or alleviate its effects on any foreign country he chooses, any time he wants to.

Whether Congress has the nerve for this gambit is another question. The GOP majority in the House is brittle, and key Republican senators, including Majority Leader John Thune, hail from states that need foreign trade as much as the senators themselves need Trump’s voters. And if some of those states need the trade more than their senator needs Trump’s goodwill, the President will have a revolt on his hands well before next year’s midterms.

Does Trump have any reason to worry, though? Bullets couldn’t stop him last year. If Congress reins in his trade authority, he’s no worse off than if he had never used that authority in the first place. His idea of his legacy is not tied to the GOP’s electoral prospects. The party is his vehicle, not the other way around, and if stands in the way of his aims – however grand they may be – so much the worse for the party. He’s bigger than any elephant. And if he’s not really planning to run for a third term, unpopularity need not concern him, either. He knows the American public very well, and a segment of it will love him no matter what, perhaps all the more if he overreaches.

The tariffs, like most other policies of this administration, are not about utilitarian calculations, whether political or economic. They’re about grandeur, in triumph or tragedy. Trump has only flown higher after every bankruptcy and setback. Indeed, the bigger the setback, the bigger the comeback, as he proved last year. Notions like success and failure are just points on a map. And Trump isn’t only redrawing the map; he is the map.

Leave a Reply