Fans of that beloved British cultural institution Doctor Who are wont to talk about “their” doctor — that is, which iteration of the character was their entry point to the franchise. The same might be said of fans of Neil Innes, the much-loved songwriter, musician and comedian who died in 2019, aged seventy-five.

Creating happiness seems to have been one of Innes’s gifts, in public as well as private

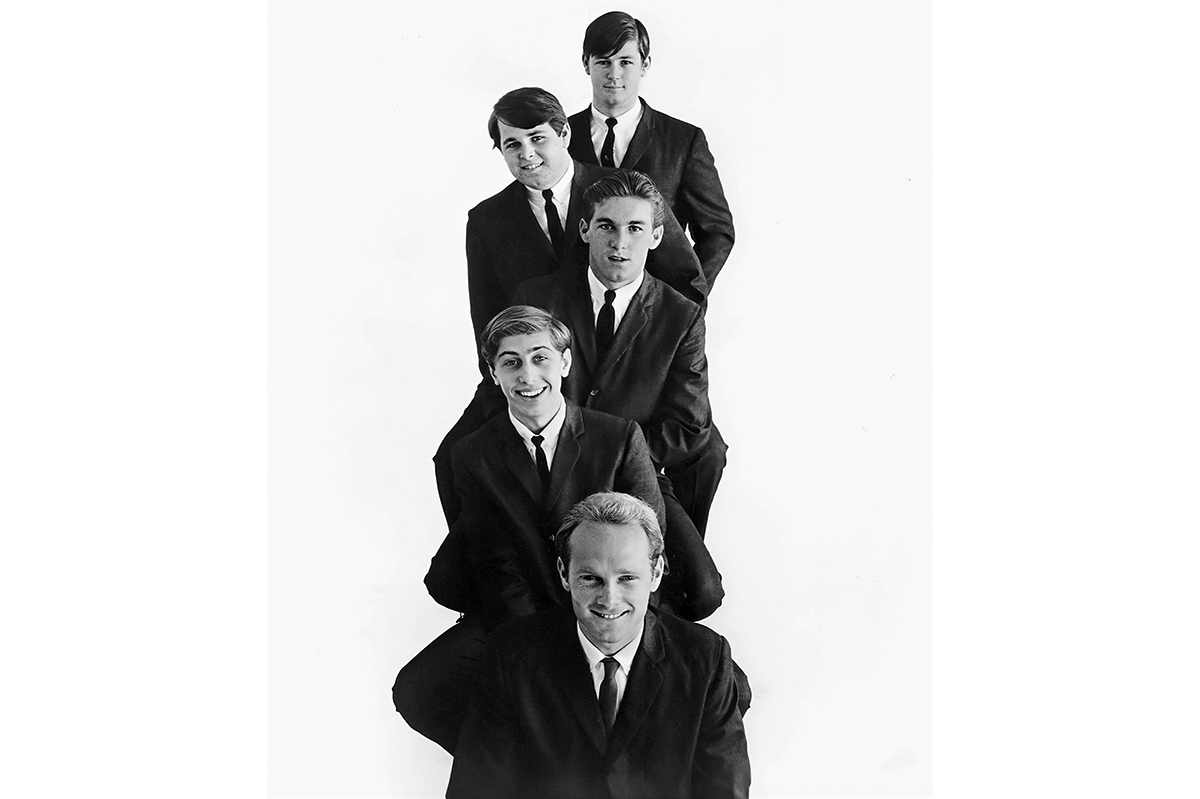

In the 1960s, Innes was a key member of the exhilaratingly unpredictable Bonzo Dog Band, whose blend of verbal, musical and visual humor remains matchless in its absurdity, breadth and daring. He was the band’s de facto musical director, or, as he described it, the “misery guts who kept saying lets’s all play the same chords at least 80 percent of the time” — a policy some Bonzos found dictatorial. He and his fellow songwriter Vivian Stanshall were the Lennon and McCartney for a generation of awkward kids who looked askance at the grown-up world and took comfort in laughing at it instead.

In the 1980s, another generation of outsiders discovered Innes through The Raggy Dolls, an animated series for children, for which he performed all the voices and wrote every episode. It followed the adventures of a group of misshapen dolls who found themselves in the factory’s reject bin. Others will know Innes from his work as a member of the Monty Python team, primarily when they performed live in the 1970s. He went on to form a close working relationship with Eric Idle. The two collaborated on Idle’s Rutland Weekend Television, which itself spawned the glorious All You Need is Cash, a film about the Rutles, a parody of the Beatles, for which Innes wrote some twenty songs, all powerfully evocative of the Fab Four while fresh and joyously themselves. Then there were three series of The Innes Book of Records for the BBC, in which Innes performed his own songs while playing multiple different characters.

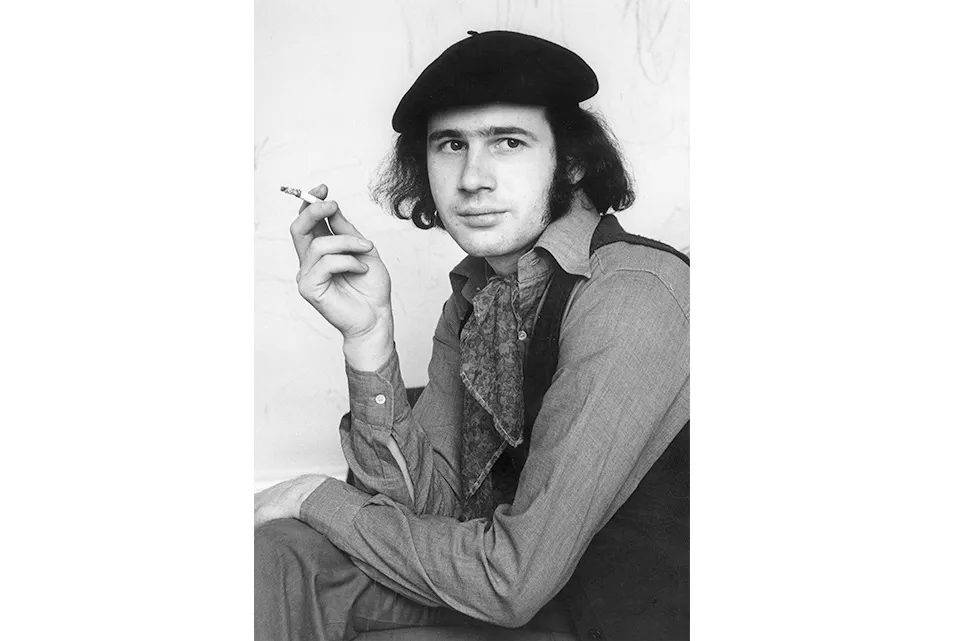

But, as his widow Yvonne reveals in Dip My Brain in Joy, her moving memoir of their life together, Innes was emotionally ill-adapted to the bear pit of showbiz. He was born in 1944 into an army family and, perhaps because of an early peripatetic life, his instinct socially was to fit in. He picked up and unconsciously mirrored mannerisms and accents within moments of meeting people – a clue to his talent for parody. A calming presence in any situation, he was also pathologically averse to confrontation. He soothed away his sorrows and frustrations with wine and industrial-strength cigarettes.

Stubbornly protective of his creative routines, Innes hated dealing with the business side of his career. The aversion cost him dearly. The Rutles soundtrack was nominated for a Grammy; but ATV, which owned the rights to the Beatles’ catalog, sued, and Innes’s own publisher capitulated. Contractual problems stopped the BBC re-running The Innes Book of Records. His last album was successfully crowdfunded — only for the crowdfunding platform to go bankrupt and swallow up most of the money.

And then there was Eric Idle. It isn’t clear why they fell out. But when Innes was approached to revive the Rutles for an album to parody the Beatles’ Archaeology project in the mid 1990s, Idle stalled it by suing over the rights to the band’s name, which he owned. The album did eventually limp out, but the timing — and the budget — were gone. “You’re supposed to be sending us up, not emulating us,” a friendly George Harrison said.

Dip My Brain in Joy is positioned as the official biography, but it is much more a memoir of a marriage. Innes was a sublimely gifted parodist and a writer of lovely, wistful songs that balanced wit with deep, often melancholy, feeling. Very few people combine humor and pathos so effectively — John Cleese compares him with Charlie Chaplin — and his work will hopefully receive a fuller account one day.

Tensions between the couple surface occasionally, since money worries are constant; but their long marriage appears both strong and indelibly happy, a charmed life steeped in love. Creating happiness seems to have been one of Innes’s gifts, in public as well as private. His approach to living — “Not to say no when there is a way to say yes” — has much to commend it.

But pangs of loss recur. “There seemed to be years of youngness ahead of us,” Yvonne writes poignantly of their youth, and her grief at his loss still seems livid and raw. In a couple of passages she slips into the present tense, as if the unthinkable has still yet to happen. The last sections of the book, on Innes’s sudden death and its aftermath, are painful to read.

“We decided to go back to where the nice people were and enjoy what we’d got,” Yvonne writes, after describing yet another setback. “And so, I like to think, we won that way.” On this reading, they really did.

Leave a Reply