“Could we get a precise definition of fascism before all this kicks off today?”

So asked Merryn Somerset Webb, a senior columnist at Bloomberg, just before polling day in America.

It was — and is — a question worth asking. The election of Donald Trump was inevitably going to draw the comparison, particularly after Kamala Harris (remember her?) said that she believed Donald Trump “is a fascist.” There is even a Wikipedia page on “Donald Trump and fascism.”

When the guests on The Rest is Politics American election livestream asked themselves whether Donald Trump is a fascist, Rory Stewart answered “I don’t think yes or no is very useful,” Marina Hyde answered “potentially, yes,” Anthony Scaramucci answered “he’s a fucking fascist — he’s the fascist of fascists” and Alastair Campbell said he thought Trump was “well down that road.” Predictably the only sane voice in the room was Dominic Sandbrook, who said he didn’t think Trump was a fascist, before going on to explain that fascism “is a very time-specific thing that emerges in the debris of the first world war” and that Trump does not have a paramilitary force, a cult of war, a plan for aggressive expansion or the ideological dynamism to remake society — in particular new men.

Sandbrook is right. Trying to define fascism is a difficult thing; it is, as Ian Kershaw once wrote, “like trying to nail jelly to the wall.” But Stanley Payne’s definition, centered around three key elements, is probably best:

- Fascist negations: opposition to liberalism, communism, and conservatism

- Fascist goals: establishing a nationalist dictatorship aimed at regulating the economy & its structures, reshaping social relationships within a modern and self-determined culture, and pursuing national expansion into an empire

- Fascist style: a distinctive political aesthetic characterized by romantic symbolism, mass mobilization, a glorification of violence, and an emphasis on masculinity, youth, and charismatic authoritarian leadership

In that livestream, Alastair Campbell asked Scaramucci for a definition of fascism “as it relates to Trump.” A telling moment; the definition is qualified. The value required is not absolute, but relative. The reality — whether Trump is actually, factually, correctly a fascist — doesn’t matter. What matters is whether Trump is considered a fascist relative to how Scaramucci would define one.

So, if you want a convenient definition, it is this: right-wing politics I don’t agree with.

It really is as simple as that. There’s no grounding in historical understanding, no insight into political ideology, no comprehension of aesthetics. To suggest there is gives those who use it too much credit. These people are just stupid. As George Orwell wrote — in 1946! — “The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable.’’’

Here are a few examples:

- Javier Milei Is the World’s Latest Wannabe Fascist

- How Boris Johnson became an accidental fascist

- Giorgia Meloni and the return of fascism; The programs of Ronald Reagan do not yet constitute a full-fledged fascist program, but rather a groundwork for fascism

- Exploring protofascism in George W. Bush’s post 9-11 speeches

- The Fascism of Benjamin Netanyahu; Fascists summoned from above: Braverman must go

This is a short list, but I reckon you would find that almost every prominent politician to the right of the wettest Republican or Conservative has been called a fascist. No coherent political ideology could possibly bind these people together — other than the relative definition of right-wing politics I don’t agree with.

As I’ve written before, our inability to escape the shadow of the second world war, or to stop comparing ourselves to the moral übermensch of the Greatest Generation, is completely understandable. Its narrative simplicity lends itself to sophistry:

The horrors of Nazism are the defining moral event of the modern age. The Nazis were such a perfect evil and revulsion to them is so universal that it creates a black-and-white sense of good and evil that plays perfectly to the all-or-nothing nature of contemporary debate: other definitions of evil necessitate context, and, if they aren’t well known, become diminished through explanation. The commonality of abhorrence to Nazism, however, has given us what Alec Ryrie describes as “an all but universally accepted definition of evil, a fixed point on our moral compass.”

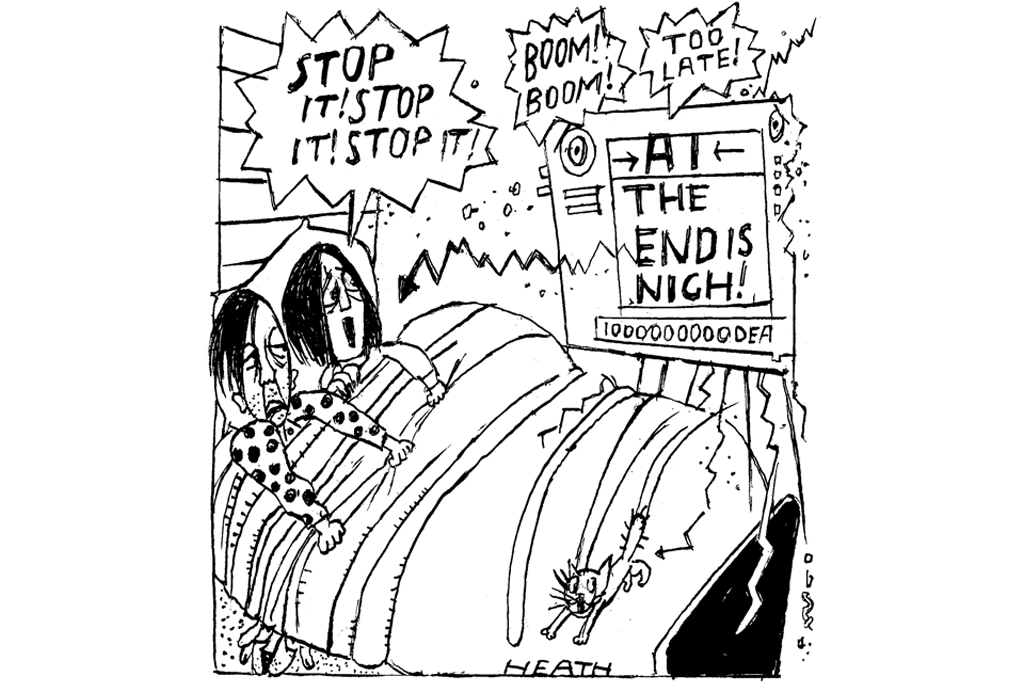

As a result, Nazism or references to Hitler have become ubiquitous in public debate. This isn’t, of course, a mark of quality. Reflexively comparing an opponent to the Nazis is obvious and invariably the hallmark of a poor argument, when the accusation alone is intended to be sufficient proof of guilt. That Godwin’s Law came into existence with the internet is no coincidence — the increase in quantity of arguments seems to have done nothing to increase their quality. The regularity with which Nazism is invoked — particularly, inevitably, against those on the right — should serve to remind us that humans are usually more predictable than they are original.

I suspect, when there was some cultural and living memory of fascism, when there was an understanding of what it meant and an appreciation of its significance, the term might have had some impact. But, after the semantic change from the absolute to the relative, it doesn’t.

Despite the constant usage, the anti-right remains baffled as to why it doesn’t work and why things keep (in their eyes) getting worse. Perhaps, instead of consuming Orwell via Wikiquotes and secondhand through Black Mirror, they should actually read him. As he noted in Politics and the English Language:

One ought to recognize that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language, and that one can probably bring about some improvement by starting at the verbal end. If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself…

The diminishing returns from its current discourse are ever more apparent. Increasing numbers of young people are turning to the right; and who can blame them, when for years now terms like “racist,” “white supremacist,” and “literally Hitler” have been wielded so frequently and indiscriminately that they no longer have any weight. They have devolved into catchphrases that most people now instinctively tune out — and this is particularly true of the younger generations who grew up online.

They continue this line of argument because the Left is completely rhetorically exhausted. They have no great ideas to communicate, and no great communicators to do it. The best they can offer is negation (opposition to the right) or an attempted co-opting of right wing culture (see: Dark Brandon, Aaron Bastani). No one — unless the government has been so bad that the negative position works — is listening anymore.

Will they try and give people a positive reason to vote for them, or carry on calling people fascists and wondering why it doesn’t have the effect they think it should? The bovine intellectual incuriosity that marks much of the modern Left means it will, almost certainly, be the latter.

This article originally appeared in Tom Jones’s Substack, the Potemkin Village Idiot.

Leave a Reply