The United States of China, anyone? The idea that a federal China might be able to accommodate within it a relatively autonomous Taiwan is one of the more radical solutions mooted to the thorny problem of Taiwan’s status. The difficulty, of course, is that neither the Chinese Communist Party nor Taiwan’s leaders would find such an outcome remotely acceptable. The CCP will not countenance a loosening of its control over mainland China; the Taiwanese, for their part, see in Hong Kong’s recent sad trajectory a vision of their own future should their politicians ever accept an offer of special status within China.

At the other end of the spectrum lies the possibility that a sacrifice may one day be made of Taiwan by its erstwhile friends around the globe — offered up to China in exchange for a bit of peace and quiet alongside a stable global economy. To many, this smacks of appeasement. Yet any attempt by a powerful and determined China to force Taiwan into the fold would carry extraordinary risks. How many civilian casualties and how much damage to Taiwan’s infrastructure would the island’s leadership tolerate before giving in to Chinese demands? And when push came to shove, how far would the Americans and the Europeans be prepared to go to help Taiwan defend itself? Alongside the appalling economic fallout should maritime trade suffer serious and prolonged disruption there is the prospect of escalation between the US and China culminating in a nuclear exchange.

For Kerry Brown, a former diplomat and now professor of Chinese studies at King’s College, London, talk of Taiwan as an international flashpoint tends to obscure the experience of the people who call it home. The Taiwan Story is in part an attempt to remedy this, offering readers a short survey of the island’s history and in particular its trajectory since Chiang Kai-shek and his army fled there from the mainland in 1949. Intended as a temporary retreat during the Republic of China’s fight against the Chinese communists, it ended up becoming home. The result has been two Chinas, their paths steadily diverging across the second half of the twentieth century and into the present.

Brown reveals Taiwan to his readers as a place of fascinating pluralism, where the culture of the island’s aboriginal peoples has mixed and mingled with Chinese Confucianism, Christianity, the legacies of Japan’s colonial empire, industrial modernity and, most recently, liberal democracy. We learn of the wildly successful bet made, back in the late 1980s, on semi-conductors, which have since become integral to our computerized way of life. So complex are the technology and associated supply chains required for making the most advanced chips — just one of the lasers used in the process contains more than 450,000 components — that even now China remains around a decade behind Taiwan in this crucial endeavor. Analysts talk of Taiwan’s “silicon shield”: so essential is the island to global electronics that even China may think twice about risking the profound economic instability that an attack would bring.

The Taiwan Story is less a deep dive into Taiwan’s life and culture than a clear-sighted assessment of the international trade-offs that govern its people’s fate, most of all the trade-off between prosperity and security. “Chinese conflict with Taiwan,” writes Brown, “would remake the world, leaving behind it a planet that is poorer and even more profoundly divided than it is at present.” Yet analysts disagree, we discover, over the value of the silicon shield. Taiwan’s semiconductor supremacy surely serves to heighten the territory’s value to China. And should production be set back during an attack on Taiwan, China’s competitors would suffer just as much as China itself. All this is part of a deeper fate that the Taiwanese have come to share with other peoples in the region: having China as their major trading partner and the US as their major security guarantor.

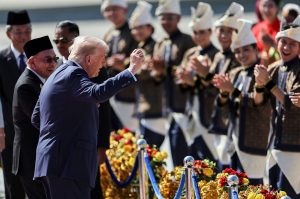

A difficult reality, no doubt — but, argues Brown, the alternatives are worse. He makes a strong case for the status of Taiwan being essentially irresolvable on the basis of current thinking about sovereignty and identity, both within East Asia and beyond. It is possible that our conceptions may evolve, says Brown, citing climate change as an example of a challenge that has required new thinking about sovereignty and international co-operation. In the meantime, the priority must be to avoid what he calls “zero-sum thinking”: an insistence on seeing the Taiwan question as part of an inevitable cultural and ideological clash between China and the West which must one day be settled in armed confrontation. Brown notes the unhelpful role played here by politicians, including Mike Pompeo and Liz Truss, who visited Taiwan after leaving office and made grand pronouncements about a “global battle for freedom” (Truss) rather than seeking to understand the complex sensitivities of this particular issue.

There are situations, thinks Brown — and no doubt this is the diplomat in him — where stalemate is actually rather a good outcome. Profoundly uncomfortable though it must be for the people of Taiwan, the best that we can presently hope for is tacit recognition on all sides that we currently lack the means to solve this particular dilemma. Passing on one’s problems to a future generation is usually considered bad form. In this case, it may be an act of great wisdom and mercy.