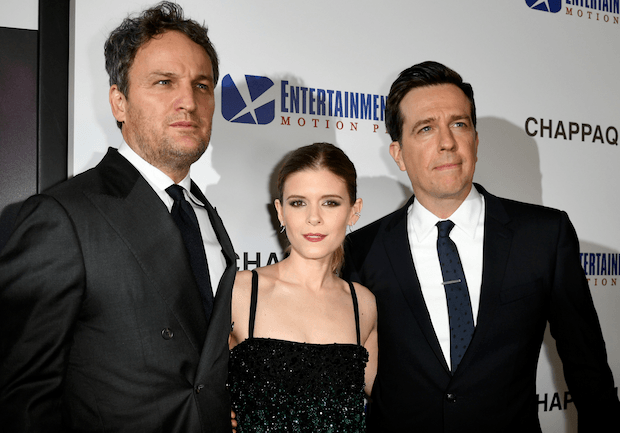

They called Ted Kennedy the Lion of the Senate. He spent most of his time stuffed, satiated and asleep, and the rest of it on the prowl for young flesh. He also had a hand in numerous pieces of legislation. But the only thing he will be remembered for is leaving Mary Jo Kopechne to die at Chappaquiddick in 1969. Judging from Jason Curran’s carefully constructed and brilliantly played Chappaquiddick, Ted Kennedy deserved nothing less—and a lot more than a two-month suspended sentence.

The Kennedys were a mafia. Ted was their Fredo Corleone. The family bailed Ted out when he was caught cheating at Harvard, then slid him into JFK’s empty Senate seat when JFK moved to the White House. The killings of JFK and Bobby left Ted as the head of the family, and in the crosshairs. Taylor Allen and Andrew Logan’s crisp script opens with Ted the youngest majority whip in American history. All he has to do is walk in a straight line to the Democratic nomination and a shot at the White House in 1972.

‘Will Ted Kennedy run?’ a newscaster asks. Yes, but only after drinking too much and driving off a bridge. The fateful night on Martha’s Vineyard plays out against the background of the Apollo XI moon shot. But Ted is more Dickarus than Icarus, and barely tries to fly as high as his brothers had. Like Neil Armstrong after leaving the Moon, Ted’s more interested in a smooth re-entry, in this case after a party with the Boiler Room Girls, a group of young women who have worked on Bobby’s campaign for the Democratic nomination, and might work on Ted’s, should he summon the nerve.

Chappaquiddick is a drama not a legal indictment, but that makes it all the more devastating. Like the court that let him off with a slapped wrist, Chappaquiddick takes Ted at his word—his suspicious failure to report the accident, his apparent attempt to create an alibi, the falsifications in his written statement to the police, his bizarre behavior after the story broke, his falsifications of the record in court, and the further falsifications of his televised statement in the court of public opinion. We have only Ted’s word that he repeatedly tried to save Mary Jo Kopechne. And Ted’s word, Chappaquiddick shows, is worthless. Personally, I doubt he even tried to save her. I also doubt his claim that he could not recall how it was that he ended up on dry land, and she ended up trapped in an upended car.

In the New York Times, Neal Gabler has accused the makers of Chappaquiddick of character assassination. Admittedly, it’s an embroidery to have Joe Kennedy, Sr., palsied by a stroke, gasping ‘Alibi!’ like an elderly Mafia don. But Gabler, an old-time liberal who is writing a biography of the ‘white-maned senator’, is protecting his professional and political investments. Ted assassinated whatever character he had. No one can complain about the necessary fictions of a film when its subject was in reality a proven liar.

Jason Clarke captures Ted’s appeal and weakness perfectly. Like Elvis after the ’68 Special or Bill Clinton during the Lewinsky affair, Kennedy is seedy and flabby, but he still has a shake in his hips and the confused, fascinating intensity of a petulant giant. When Ted breaks the news to Kopechne’s parents, he launches into a politician’s speech. They hang up, and he sobs—for himself and his weakness, and not for their dead daughter.

Two comedians play against type in this sorry tragedy. Ed Helms is superb as the Kennedy clan’s Tom Hagen, Ted’s cousin and fixer Joe Gargan. Jim Gaffigan, as Massachusetts attorney-general Paul Markham, is a moral and physical slob, a high official reduced to a drunken gofer for Ted Sorensen and the family lawyers as they conspire to cover up Ted’s crime and then, when the story breaks, spin it so that Ted, not Mary Jo Kopechne, is the victim.

In his 1988 book Senatorial Privilege, Leo Damore reports an interview with Gargan in which Gargan claims that Ted Kennedy at first tried to pin the crash on Kopechne, by claiming that she was driving. Kennedy himself was unable to explain why he didn’t report the accident for ten hours. As Chappaquiddick shows, his conduct is only explicable as that of a coward in search of an alibi. The same goes for his ludicrous donning of a neck brace for Kopechne’s funeral — the papers reported that he had no trouble turning around in his pew—and the claim by Kennedy lawyers that Ted couldn’t speak to the press because he was sedated because of concussion. They dropped that line when it emerged that sedating a concussion can be fatal.

Ted got away with involuntary manslaughter. Why wasn’t Chappaquiddick fatal to his career? Chappaquiddick suggests a combination of two factors. As the sole survivor of four brothers—his eldest brother, Joe Jr., had died a hero’s death as a wartime pilot—Ted still had the public’s sympathy. That was why his televised address included a plea of diminished responsibility, that he too was a victim of the ‘Curse of the Kennedys’.

The other reason is highly topical. At the end of Chappaquiddick, we see footage from the days after Ted’s television statement. A television reporter asks random members of the public for their opinion. Some think he is guilty, but most either don’t care or think he should stay on as senator. They find him appealing and entertaining, and that’s enough. The voters are diminishing their responsibility too.

It is customary to say that the rot in American politics set in with Nixon, who was in office in 1969. But the triumph of style over content and entertainment over ethics began in 1960, when JFK defeated Nixon, and Sorensen and a complicit media cast the quasi-royal veil of Camelot over the sleaze of the Kennedy White House. That substitution of myth for fact permitted Ted Kennedy, a person of obvious and profoundly weak character, to run for the Democratic nomination in 1980.

Chappaquiddick is an antidote to the other Curse of the Kennedys: the voters’ willing susceptibility to myths. Given the quality of the current and previous presidents, Chappaquiddick feels like the best-made public service broadcast in years.