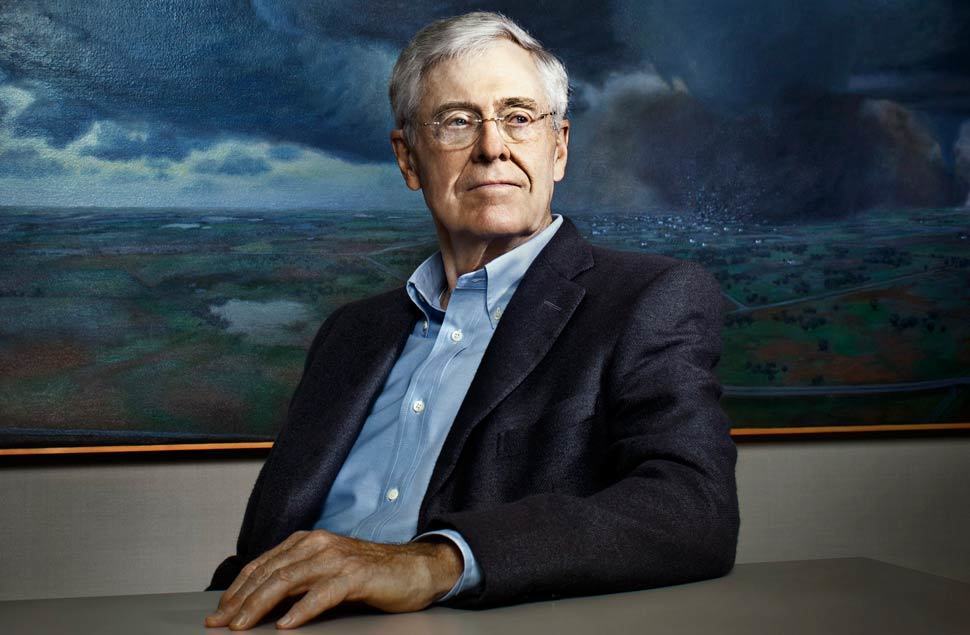

Charles Koch wants to be liked. Denounced by Senator Harry Reid as the reincarnation of the 19th century robber barons, demonised by the left as a symbol of heartless greed, a despoiler of the environment, and the financier of all things reactionary, the Kansas billionaire has embarked on a campaign to remake his image and redeem the family name. While the well-financed network of political action groups and thinktanks he generously supports are still working on behalf of his libertarian beliefs, Charles is determined to prove that he’s a Good Samaritan as well as a political ideologue: the list of good works stretches from agitating for criminal justice reform to giving generously to the arts and sciences, ramping up his contributions by many millions of dollars.

And to take the edge off his public image, he told an interviewer that he no longer considers himself a libertarian – an appellation far too angular for his remade persona. He now says he’s a “classical liberal.” While the left characterises Koch – it’s Charles who’s the political one, while brother David is much less ideological – as the George Soros of the right, the Washington Post reports that the Koch network is now open to working with Democrats “in areas where they agree.” One major area where they definitely agree is immigration: the Koch-run Cato Institute has been pushing a highly liberal open borders policy, and the hostility of the Koch network to President Donald Trump has been undisguised.

Indeed, what might be described as Koch’s “left turn” is in large part seemingly motivated by the rise of Trump and Trumpism within the Republican party – a party once devoted to free trade (or, in reality, the managed trade of Nafta and the TPP) has now turned to the bete noir of the libertarians: tariffs! The various Koch outfits – Cato, the Mercatus Center, Freedomworks, Concerned Veterans of America, Americans for Prosperity – have been vigorously denouncing the “trade wars are good” line of the administration, and with the network spending as much as $400 million in the 2018 election year cycle, they pose a considerable threat to the Trumpified GOP. As the Post reported: “’We’re not going to sit back and wait, as we have in the past,’ said James Davis, a senior official at the network who oversees communications. ‘We’ve also pulled punches in a lot of places where we didn’t want to upset folks that we were going to be working with on other issues. … So we’re going to have to come out and hold Republicans and Democrats accountable.’”

Another area where the Koch network is placing renewed emphasis is an issue where the Trump administration and the right-wing populist movement within the GOP are on the other side of the barricades: criminal justice reform. The Charles Koch Institute, which has now become one of the major receptacles of Koch wealth in pursuit of “social justice,” regularly runs programs on lowering the incarceration rate, decriminalizing drugs (not just marijuana), job training, and various other schemes of social uplift aimed at racial minorities. In cooperation with the United Negro College Fund they sponsor speakers who preach the value of entrepreneurship, and their interns are busy tweeting little bromides like “What is a principled entrepreneur?” One “who acts with integrity, respect, and toleration.” “Sometimes you find extraordinary partners in unexpected places.” “You succeed,” said Brian Hooks, president of the Koch Foundation,” “by helping others to succeed. That’s ultimately what it’s all about.” A series of Horatio Alger stories, with a dose of free market ideology thrown in (but not too obstrusively) and a lot of advice about “how to leverage your network.”

It’s a long way from the Koch network’s origins as essentially the brainchild not of Charles Koch but of the radical libertarian philosopher Murray N. Rothbard, who first convinced the Koch family patriarch to fund a political-ideological movement. Sometime in the late Sixties, Charles summoned Rothbard to a mountain ski lodge in Vail, Colorado, and over a weekend they discussed what the libertarian movement needed – which was, essentially, everything.

In a long memo, Rothbard outlined a plan that later led to the creation of the Cato Institute, as well as two magazines, a student group, and an academic program to nurture scholars. Rothbard, author of 25 books and hundreds of articles, preached a consistent version of libertarianism that had no use for government of any kind: Koch was captivated.

But the falling out came when Koch’s ideological empire entered the world of practical politics: Koch was subsidizing the Libertarian Party, with oil company lawyer Ed Clark as its presidential candidate – and David Koch as the vice presidential nominee. David’s entry into the political arena was a convenient way to get around campaign finance laws, which limited outside contributions from a single source but allowed the candidates to self-finance their campaigns. The Libertarians had high hopes that year – 1980 – but these were dashed when independent candidate John Anderson stole the third party spotlight and Clark wound up getting less than a million votes – far less than the party leadership had promised.

The big split came midway through the campaign, when Clark – under orders from Koch’s lieutenants – refused to come out for abolition of the income tax (which Republican Jack Kemp had no qualms about doing) and waffled on several other issues. The Gotterdammerung of the libertarians came when Clark, interviewed on national television, was asked to describe libertarianism in a single phrase. His answer: “Low-tax liberalism.” Rothbard and his followers in the movement were outraged: this confirmed their theory that all Koch and his cronies cared about was impressing the liberal media and getting in the New York Times.

The factional explosion that occasioned all this took a few years to play out, but when it was over the Cato Institute – formerly ensconced at the base of San Francisco Telegraph Hill – purged Rothbard from the Board of Directors, moved to Washington, and proceeded to establish itself as the go-to thinktank for Republicans in the mould of New Gingrich. While maintaining its pretensions to principled libertarianism, slowly but surely Cato – and allied Koch groups – downplayed their former radicalism and integrated themselves into the GOP, albeit not always seamlessly.

In 2012, Koch decided that Cato wasn’t doing its part to buttress the Koch network’s political campaigns, and made a move to oust longtime Cato President Edward H. Crane III. A public battle ensued in the course of which most Cato employees sided with Crane, declaring they’d quit rather than become GOP janissaries: they launched a “Save Cato” website and made a huge fuss in the media, which, being liberal, sided with them against the despised Kochs. However, when Charles Koch prevailed and Crane left, these employees stayed almost to a man. Cushy thinktanky jobs at libertarian thinktanks don’t grow on trees.

The Koch network spent over 120 million in a vain effort to defeat Barack Obama in 2012, after which Charles decided to reevaluate his political activities. After all, what had all the years of ideological campaigning gotten him? Vilified, and defeated, the Kochs licked their wounds, drew their resources inward, and started on a new path: philanthropy (with a side dish of propaganda). They set up groups like LIBRE, which does outreach to the burgeoning Latino population, started talking about the depredations of the police in the black community, and stepped up their charitable giving: yet none of this had any measurable effect on their public image in the media. Liberals still hated them.

When Trump knocked out his sixteen rivals for the GOP nomination, the Kochs were horrified: who was this vulgar interloper? (Ironically, that’s pretty much the same attitude David Koch encountered when he tried to buy his way into New York City high society.) The network, which consists of other wealthy GOP donors in addition to the Kochs, was divided, with various moneybags financing their favorites, but Charles was unalterably opposed to Trump. He sat on his hands during the 2016 presidential election, pouring his resources into local campaigns.

Having strayed this far from his original vision – after all, Charles was once a student at the Freedom School, an anarchist organization based in Colorado and headed up by an eccentric pacifist – the Kansas would-be kingmaker and his quasi-libertarian cadre are now looking to find renewed influence in the anti-Trump “Resistance.” Cato’s once solidly anti-interventionist foreign policy department shows signs of echoing the same anti-Russian hysterics as the bluest members of Congress. A recent Washington Post op ed by their resident cyber-“expert,” Julian Sanchez – formerly a dedicated opponent of government spying – denied that the Obama administration’s unmasking of top Trump campaign officials was any big deal. Cato was a major cheerleader for gay marriage, and their opposition to anti-discrimination laws has been thrown overboard. Low-tax liberalism rides again!