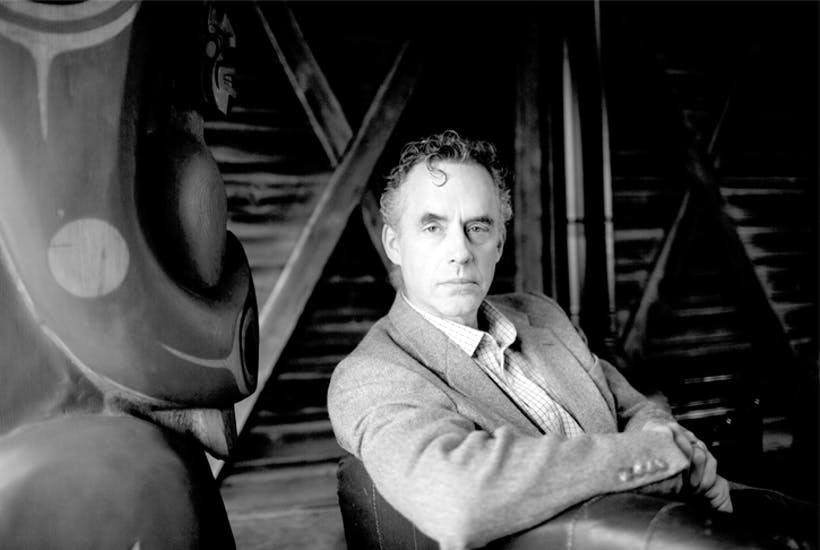

Now that I seem to have become a prophet of doom, I wonder whether I should have been a guru instead. Doom doesn’t sell. Bookshops hide my books in back rooms. My recorded harangues and TV appearances reach a few thousand dedicated YouTube enthusiasts. But Dr Jordan B. Peterson, supposedly as reactionary as I am, speaks to millions. His new book 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos adorns the front table of every Waterstones. Annoyingly, friends of mine recommend his lectures to me, people on Twitter tell me incessantly that I ‘must’ explore his work. They become positively rude if I express reluctance.

How has he done this? Is he a cult? Should I too be a cult? Is it the way to reach minds otherwise closed to conservative thought? I sometimes receive rather moving letters from readers who assure me that I have changed their lives for the better, which I must confess I never set out to do.

Should I then write a self-help manual of my own, with the working title Pull Yourself Together! and bracing chapters such as ‘A brisk walk — the cure for almost everything you think you’ve got’ and ‘They put your face on the front of your head for a good reason’ (this is directed at the users of smartphones)? Perhaps not. I suspect it would not be soppy enough. I suspect this especially after spending several days glowering at the pages of Dr Peterson’s new volume.

Let me say first of all that Dr Peterson’s recent stand against the Thought Police of his native Canada was noble and brave. He refused to be bullied into using gender-neutral pronouns. And by resolutely resisting this pressure, he overcame it — at least for now.

But as a prophet of doom I need to add that I am not sure he has won any really significant victory in the long war against radical speech codes and sexual revolution. I am ceaselessly amazed, as I look at our media, political parties, schools and universities, how formerly conservative people and institutions have adapted themselves to ideas, expressions and formulations which they once rejected and confidently mocked. Almost everything that was once derided as the work of the ‘loony left’ or ‘political correctness gone mad’ is observed daily in grand, expensive private schools and is the official policy of the Conservative and Unionist party, or soon will be.

And despite Dr Peterson’s courage, I cannot love his book. Most of it is written in a conversational style intended to be friendly and accessible. But for anyone educated before the cultural revolution, used to the orderly architecture of argument, it slides about on the page like mental porridge. It was not just my eyes that repeatedly glazed over as I perused it on my homebound train, but my brain and my entire body.

Various things seemed to keep coming round again, especially his view of the stories of Sleeping Beauty and Hansel and Gretel, and his explanation of the Garden of Eden. He recapitulates a lot. Perhaps the book is like this because it is based on his lectures. I was also urged to watch these, but, when I did, my eyes and mind strayed.

The great Colin Welch once said that, while trying to read Harold Wilson’s memoirs, he found his attention irresistibly drawn to the small print on discarded bus tickets or beer bottle labels. It is not quite that bad. But whatever it is that has made Dr Peterson a hero to so many, I do not think it is his prose style. Here is an example (page 201) of the higher Peterson: ‘Meaning is when everything there is comes together in an ecstatic dance of single purpose — the glorification of a reality so that no matter how good it has suddenly become, it can get better and better and better more and more deeply forever into the future.’ Ah.

Yet amid all this stuff are several genuinely moving moments — often personal confessions or stories of Dr Peterson’s clients illustrating the way in which we can all too easily destroy ourselves and others by choosing to do or say the wrong thing.

There is also some good advice for troubled, lost people, given by a man who has had quite severe troubles of his own, and whose face, in some lights and attitudes, looks a little like that of a sorrowing saint on an Orthodox icon. Yet I am perplexed by the fact that Dr Peterson has in the past taken ‘antidepressant’ pills. Is he aware of the scientific and medical controversy surrounding the claims made for them, and the possible disadvantages of taking them? They seem to me (even if they work as claimed) to be a version of Aldous Huxley’s soma, the drug that reconciled the inhabitants of Brave New World to their servitude and ignorance.

Perhaps this is why I am so glad that the whole nature of Dr Peterson’s work is alien to me. I am too keenly aware of the good things which have been utterly lost in recent years to be comforted by what looks like an attempt to reconcile us with the revolutionary order. I find it hard to applaud efforts to help me adapt to a world which I think has gone utterly wrong. His message is aimed at people who have grown up in the post-Christian West. I think it appeals especially to young men. And I think this is mainly because those young men cannot work out how to behave correctly towards modern young women. These young women’s minds have been trained to mistrust masculinity. But in their hearts they still despise feeble, feminised men. The outcome is that men are trapped in a minefield, in the midst of a quicksand. Whether you stand still or move, it will still destroy you. I do not know how anyone copes with it, or ever could.

I used to joke that my upbringing, among warships and cathedrals, with longish spells in chilly prep schools surrounded by muddy playing fields and ruled by bellowing tyrants, had not done me any harm. In truth, I am sure it did do me some harm, though I was neither beaten nor subjected to indecent assaults, as everyone else seems to have been. But by comparison with the world in which Dr Peterson’s poor, sad admirers have grown up, it was a wise education for real life, especially the hymns that still echo in my mind, with their promised nights of doubt and sorrow and their steep and rugged pathways.

Peter Hitchens is a columnist at the Mail on Sunday.