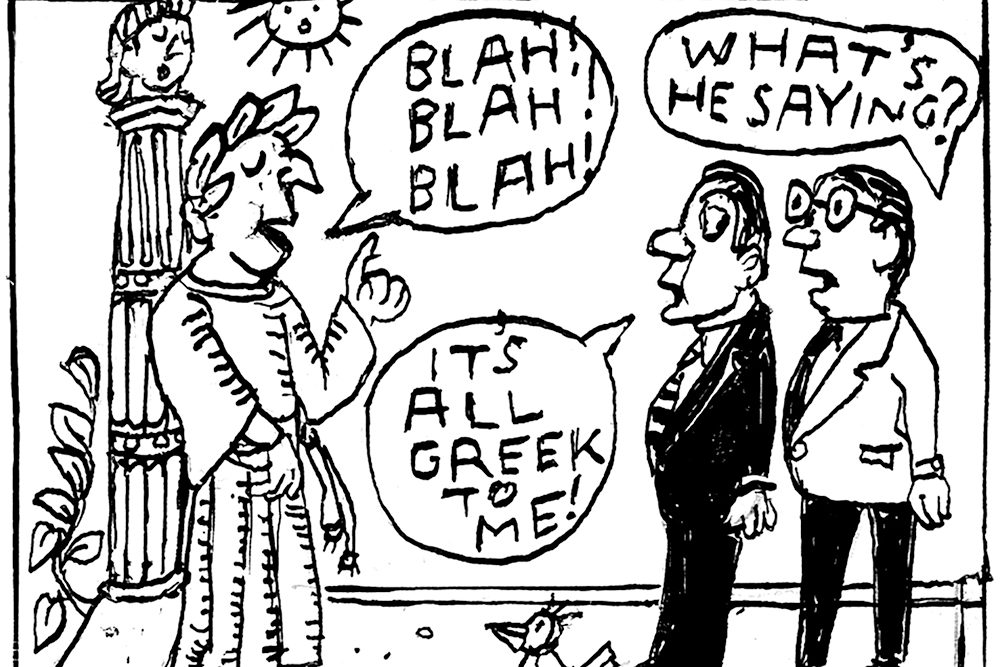

If you’ve witnessed (or rather, heard) the marches, riots and anarchy in support of DIY separatist nation-building tearing through your television set on a nightly basis, you’ll have likely noticed — between the flashbangs and sirens — something of a linguistic leitmotif. The ‘F-word’ is having a moment.

The participants in these — let’s say, indecorous — stunts seem to communicate in a language all their own, one not so much spoken but chanted in bite-sized barbs or sprayed in a loose, fast hand. Given the precarious nature of live reporting at scenes of Champ de Mars-like mayhem, censorship has proven awkward, if not impossible. Perhaps a bit of brassy sloganeering has weaseled into your very living room, like a brick through stained glass. Uninvited, it chafes. It feels seamy. Such ugliness from such little words. You may have even let slip a little ‘F___ this’ of your own under your breath.

Once the razor-sharp ‘Piss Christ’ of the English lexicon, the F-word now seems more akin to ‘The Scream’: neutered of semantic utility or illicit charm by its ubiquity on cardboard placards, Jersey barriers, monuments and in the dirty mouths of raving undergrads from College Station to Saint Paul. At its most derogatory and humiliating (as a verb or noun) or flippant (as an adjective) it is a word of little value or aesthetic appeal. And yet its frequency in contemporary speech — perhaps because of its singular ability to offend — is remarkable, and, in the hierarchy of curses, near-unrivaled.

Take, for instance, the aforementioned campagne — excuse my French — against police departments by the malcontents of today. They employ profanity as a weapon against order, against beauty, against the conscionable. Like a unit of Green Beret ‘special advisors’, they deploy the F-word early, to ‘set the stage’. With increasing incidence, it becomes part and parcel of the confrontation and lingers long after the battlefield is silent in kaleidoscopic hues of Krylon spray paint. It’s emancipatory, we’re told — from authority, from capitalism, from bourgeois morality, from God — and perfectly appropriate, says psychologist Steven Pinker, for ‘those moments in life when the point for politeness has passed’.

Context is important. In the debauched white-collar charades of Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, cussing is mere decoration and thoroughly defanged. When applied with discretion and careful timing, however, the right dysphemism, as Pinker calls the F-word, still dazzles or disgusts. The solitary ‘F-bomb’ of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, depending on your brand of politics, did one of these. That poem’s obscenity trial in 1957 was an ideological fracas that would eventually ripen into the heady culture wars of the Sixties.

I remember when the F-word fell on the ear like a hammer. When it had teeth, you wouldn’t dare kiss your mother with ‘that mouth’. Well, goodbye to all that Victorian snobbery. It’s our very mothers who’ve assumed the mantle of four-letter fandom, anyhow. The F-word (and the S-word, the ‘C-word’ and the whole lot of them) is, finally, anodyne table talk. Manners? How démodé. The ‘decolonization’ of the Queen’s English is, I’m afraid, fucking total.

With ‘progress’, however, something is irrevocably lost. Two obituaries in the June 27 edition of the New York Times shared this sentiment, the bittersweet tang of acceptance. ‘Once that happens,’ argued graphic artist Milton Glaser, ‘everything becomes less interesting.’ Clinician and scholar Kenneth Lewes lamented the same effect in America’s embracing of ‘the gay outlaw, the defier and challenger of traditional social values’. How does one rail against the status quo when one is the status quo?

***

Get a digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $3.99 a month

***

What defines the counterculture now is not the transgressive but the modest and faithful, an English that is measured, studied, benevolent and seductive in its composition and delivery. It is the inheritance of a decent, merciful people — the men and women putting paint thinner and power washers to graffiti-smeared stone — not a vengeful one; not the privilege of any class, but of a particular cast of mind that chooses to recognize and appreciate the wonder and mystery of existence, not its ineradicable inequities; not a sanitized anachronism, but the living tongue of a proud and tolerant civilization wounded but poised for renewal. Whoever’s statues fall this summer, justly or not, let it be said I saw the best minds of my generation abandon histrionics for the hard work of stewardship.

Desecration requires little in the way of skill or investment, but creation does, in spades. It also wants for lingo worthy of its high ideals, for words that feel good in the mouth. Let it be said we crafted arguments for the sake of dialogue in pursuit of forgiveness and reconciliation, not divorce. For ‘there is nothing’, the New Testament counsels, ‘that enters a man from outside which can defile him; but the things which come out of him, those are the things that defile a man’.