I have some thoughts on poetry and morality coming soon to a publication near you, but in the meantime, let me direct you to Alice Gribben’s wonderfully gripey piece in Tablet on how the contemporary art world is ruining art:

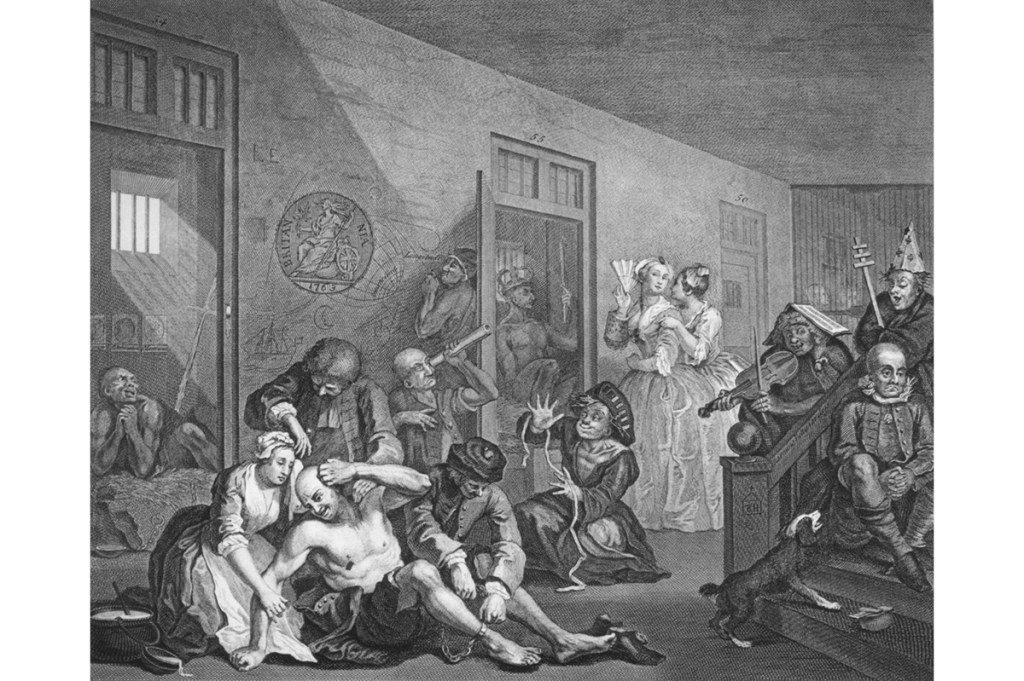

Artworks are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear.

This vulgar and impoverishing approach to art denigrates the human mind, spirit and senses. From where did the approach originate, and how did it come to such prominence? Historians a century from now will know better than we do. What can be stated with some certainty is the debasement is nearly complete: the institutions tasked with the promotion and preservation of art have determined that the artwork is a message-delivery system. More important than tracing the origins of this soul-denying formula is to refuse it — to insist on experiences that elevate aesthetics and thereby affirm both life and art.

Do read the whole thing.

One publication in New York that has rejected the idea that art is a “message-delivery system” is the Drunken Canal. You may recall reading that Vanity Fair’s profile of them last year. In the New Statesman, Nick Burns writes about the conflict between the libertarian Dimes Square crowd and the self-important mothers of socialism in Brooklyn. It’s a good read, but Burns is taking New York way too seriously when he writes: “Who wins in New York’s clash of cultures is high-stakes for the future of American political culture. One does not have to go far back to see how scenes deemed cool in New York often become political reality.”

In other news

Robert Messenger writes about the pleasures of reading and handling a David R. Godine book: “One of more spectacular publications I bought in recent years is the Godine edition of The Prelude: not only newly edited with a full scholarly apparatus but also boasting two hundred and seventy paintings and watercolors contemporaneous with Wordsworth’s autobiographical poem. The images are placed directly in the text in the appropriate position. The layout is airy and generous, the book’s trim size a fetching nine by twelve inches. No decision seems to have been made on the basis of cost or commercial viability. The decision was instead to make something lasting, something beautiful.”

A history of wiretapping: “In 1965, a private investigator named Harold Lipset appeared before a Senate subcommittee and took a sip from a martini. That part was a little unusual, but it was what the glass contained that shocked lawmakers. The pimento in the facsimile of an olive concealed a miniature recording device; the toothpick was an antenna. Near the end of his testimony, Lipset played back his own opening statement. He had been recording the whole time.”

Against “awareness”: “Awareness has come to be considered a self-evident good. News outlets carry laudatory stories of local citizens and groups engaging in attention-grabbing feats to “raise awareness” of an illness, an issue, a threat. No sooner do events hit the headlines than social-media profiles alight with filters and flags demonstrating awareness of, and concern for, whatever the Current Thing may be.”

Mark Bauerlein reviews Robert A. Gross’s The Transcendentalists and Their World: “Why Concord? That’s the question historian Robert Gross asks at the beginning of this weighty study of the hottest setting of literary-philosophical thought in antebellum America. (Weighty, indeed — the volume in my hand has 608 pages of text, 178 pages of footnotes, and fifteen pages of acknowledgments.) It’s a good question. Why should this unexceptional town twenty miles west of Boston with no natural sublimity or intellectual history, no great universities or popular theaters or bustling coffeehouses, no patrons or publishers, have produced such a lasting body of writing in so brief a time, the first real cultural movement in America that counted in the world’s eyes?”

The new Top Gun is better than the first Top Gun. “Just. Maybe,” says Deborah Ross, and the first one was not as good as you think it was.

Rachel Lu reviews Avram Alpert’s The Good-Enough Life: “My expectations for this book were quite modest, but Alpert still managed to disappoint.”

Christine Rosen reviews a new book on how politics is ruining medicine: “As Dr. Stanley Goldfarb, a nephrologist and associate dean for curriculum at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, writes in Take Two Aspirin and Call Me By My Pronouns, the ‘quiet woke revolution’ that had been going on in medicine for some time ‘erupted in spring 2020 into a full-blown revolution’—one with ongoing negative consequences.”

Miles Smith reviews Yoram Hazony’s Conservatism: A Rediscovery: “As an Israeli, Hazony’s distance from the United States’ contemporary political cacophony allows him to see clearly what is obvious from the historical record. George Washington and the Federalists, for example, were nationalists by most measures. Moreover, the religious disestablishments of the 1780s did not secularize society. Instead, the Christian religion and the state stopped their 1,300-year-old tendency to meddle in each other’s affairs and became allies in the creation of the Early Republic United States. All of this is self-evident in American history, but few recent authors have dared say so.”