Old tortoise that I am, my head usually yanks back into my shell when people start talking about artificial intelligence. One reason for this is laziness in the face of the challenge of learning to understand a deep and complex subject. I’m not proud of that.

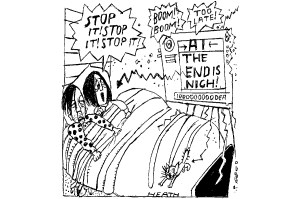

But of another reason I’m unashamed. Societies standing at the brink of a massive leap forward in technology have never been much good at predicting where the innovation will lead. The printing press, telegraphy, typewriting and motor car; the wireless and television; the telephone, the tank, the mobile phone… who would have guessed usefully at the landscape into which these inventions would usher us? The dawn of each technology will have been (indeed, was) heralded by intense and lively debate about where it would lead: debate we’d read now with a wry smile at how little we knew. So why waste our time, this time?

Could the domestic plumber one day be better regarded and better paid than the jobbing lawyer?

Nor is it that we always underestimate; we can overestimate too. I remember my father telling me that stereoscopic photography would take the world by storm. A few people did buy twin-lens cameras and viewers, but interest fizzled out. Three-dimensional movies have yet to become the norm, though both Dad and I long ago predicted they would.

He told me stereo music recording would lose its novelty value because the aim of any conductor was to achieve a unified sound; while electricity would soon be so cheap and plentiful that nobody would even bother to switch lights off any more. And Dad was a power engineer. But he couldn’t know. Nobody could.

The big new advance being AI, everyone is trying to predict. But it’s a mug’s game, though I must admit to astonishment at how useful ChatGPT is already proving in my work. My assistant employs the facility, and though we’ve learned always to review and check, it can be invaluable at providing the first dump of information (and sometimes even phraseology) and a round-up of landmark facts and arguments. A friend recently had to make a short speech in tribute to a colleague, and friends and I asked ChatGPT to have a go. We were amazed at the quality of the draft, provided within seconds.

Where will this lead? It was when discussing this later, over dinner, that conversation moved in the direction I’m usually reluctant to go. Let me take a stab at the hypothesis forming in my mind. I could be wildly wrong but, because the thought is counterintuitive, it’s worth venturing. Could artificial intelligence one day reverse the comparative social and financial statuses of blue-collar and white-collar work? Are what we call the “professions” more vulnerable to being robbed of work by AI than those we call “trades?” Could the domestic plumber be better regarded and better paid one day than the jobbing lawyer?

The professions we were discussing were accountancy and law, though the medical profession is most immediately at risk of losing work to robots: in diagnostics, prescription and surgery. AI in medicine is already in the news. But consider accountancy. At first the use of AI will come as a boon. Think of all the fairly mindless legwork, the retrieval of records, the processing of data, the assembling, charting, calculating and presentation of accounts; the discovery and reconciling of discrepancies. AI can do a lot of this. Important questions of inspection and judgment will remain (at least for the time being) the preserve of humans, and in the short term this will make accountancy a more stimulating job by removing much of the drudgery. But drudgery means time; and time, at present, means human labor. Look at what happened to bank clerks.

We should not assume that computers will automatically replace humans: they may compete with them. Might white–collar workers’ salary levels stagnate, for fear of being priced out of the number-crunching market by AI? How many small businesses could now manage without the services of an accountant unless the latter lower their fees?

Next, our conversation moved to the legal profession. One of us thought it will prove easier with AI to get a legal opinion cheaply; lawyers — able now to use AI themselves — may have to lower their fees. My own view is that researching possible precedents in case law may require a grasp of abstract reasoning not yet given to computers, but I may be wrong.

In summary, AI will be able — is already able — to remove millions of man-hours from a wide range of white-collar work, flooding the labor market with redundant human operatives. But what of tradesmen? Plumbing, heating, wiring, roofing, domestic repair and renovation? Housebuilding, electricians’ work, gardening, mowing, plastering, bricklaying, tiling, furniture removals, road-mending, ditch-digging, vehicle maintenance and repair? What of the catering trades, cooking and waiting-on-table? What of cleaners, nannies, nurses, hairdressers, roofers, bouncers, dustmen, foresters and dog-walkers?

Many (not all) of these trades and jobs in domestic service are low down the income scale, sometimes called “working-class,” and (many of them) lacking in social cachet. Most of them require manual work and practical skills, some require muscle, and most cannot be done by machines. Mechanization, it’s true, has eaten into job opportunities for tradesmen and farmers (this is especially true of farming) and doubtless this will continue. But artificial intelligence? I see neither threat nor opportunity.

I have never understood why in a free market we value (i.e. pay) so many of the jobs mentioned above so poorly — particularly as manual workers tend to burn out long before their white-collar fellow citizens retire. I suppose it’s because, though many require considerable training, they require less of what we’re pleased to call “education.” But it’s overwhelmingly the jobs that require “education” that are threatened by AI.

Can we, perhaps, foresee a world in which artificial intelligence makes the pen-pushers, screen-starers and laptop-tappers start running out of job opportunities, find their services less highly rewarded or regarded, and yield their place in the social pecking order to the horny-handed sons and daughters of toil? A world in which ambitious mothers hope their children marry bricklayers? I hope so.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.