What would you have done if you were Alvin Bragg? Would you have indicted Donald Trump? Or would you have walked away, concerned about accusations that you as a Democrat were playing politics, and concerned also that the indictment could help the man you were trying to take down? You don’t play with fire around a guy like Trump.

At Bragg’s insistence, Trump was indicted by a Manhattan Grand Jury on Thursday. The actual charges will not be announced until he’s arraigned before a judge, likely in about a week. The charges will, however, center on Stormy Daniels, who allegedly had sex with Trump in 2006, which he denies, and which she and Michael Cohen once also denied. She took money in 2016 to sign a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) to keep silent. She then willfully violated the NDA to revive her career, selling her story to the National Enquirer.

Meanwhile, when faced with jail time for all sorts of dirty deeds, Trump’s now-disbarred former lawyer Michael Cohen, a felon himself, violated attorney-client privilege to claim on his word that the NDA payoffs were actually complex technical violations of New York business records law (a misdemeanor) and federal campaign finance law (potentially a felony). If this all sounds complicated, that’s because it is. No wonder even the Washington Post labeled this a “zombie case.” It is also the weakest case in the universe of legal troubles surrounding Trump.

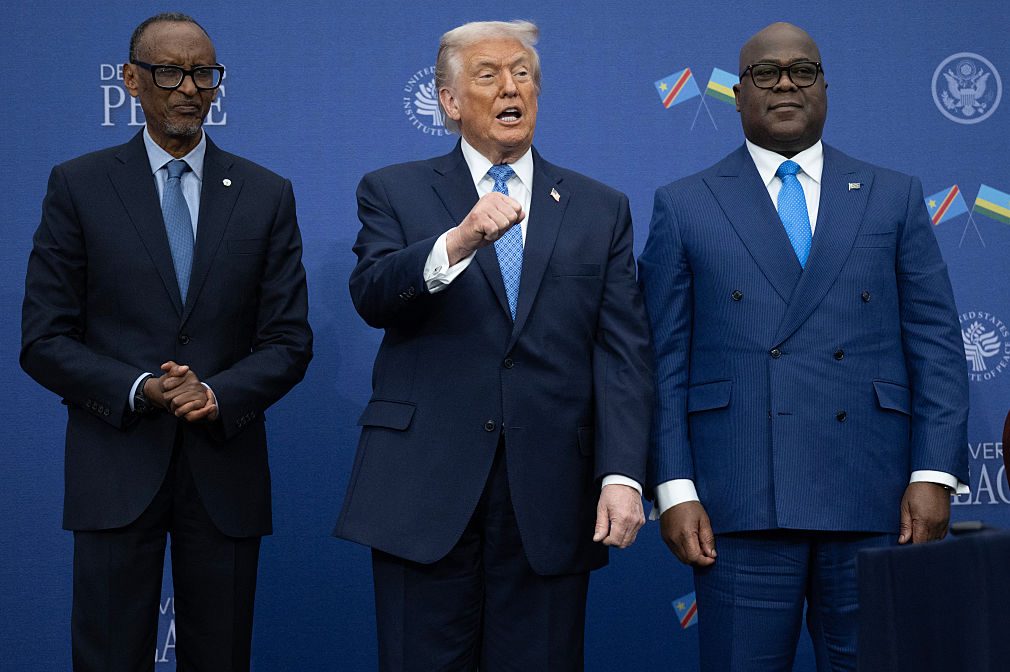

But there is a bigger question: if you were Bragg, could you win? Will voters object to a district attorney in New York trying to play kingmaker in the 2024 election, prosecuting a federal case locally in Manhattan? Candidate Trump, surrounded by an aura of legal invincibility, is already earning partisan points claiming he is the victim of banana republic politics and that this indictment will allow him to claim he was right all along. Trump will fire both barrels, one aimed at Bragg, the other likely at Biden, whom he will accuse of playing a role.

He was already the victim of a partisan misuse of justice, as the FBI tried to influence both the 2016 election (with Russiagate) and the 2020 election (by deep-sixing Hunter Biden’s laptop and claiming falsely it was Russian misinformation), and now is taking a swing at the 2024 election with the Mar-a-Lago documents. If public opinion moves further to Trump’s side, Alvin Bragg might have just reelected Trump. CIA spooks, no strangers to manipulating elections, call that blowback, and it is a real threat in this instance.

For the nation’s sake, any action against Trump must preserve what is left of faith in the rule of law applied without fear or favor, or risk civil disenfranchisement if not outright civil unrest. Bragg will have to address the case involving former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, who maintained an unsecured private email server which processed classified material. Clinton and her team destroyed tens of thousands of emails, potential evidence, as well as physical phones and Blackberries. She operated the server out of her New York (!) home kitchen despite the presence of the Secret Service on property who failed to report it. Her purpose in doing all this appeared to have been avoiding Freedom of Information Act requests during her tenure as SecState ahead of her 2016 presidential run. The Hillary campaign and the DNC also did something naughty in paying for the Steele dossier as “legal expenses” and not campaign expenditures, and got off with only an Election Commission fine.

In addition, those who claim Trump’s indictment is not political in nature will have to account for the non-actions against the Obama campaign. Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns in 2008 and 2012 were not found to have violated campaign finance laws and no charges were even levied. In 2008, donors were able to make contributions using fictitious names, such as “Mickey Mouse” and “Donald Duck,” and the campaign was criticized for not doing enough to prevent fraudulent donations. Another controversy involved the Obama campaign’s use of untraceable prepaid credit cards, which raised concerns about the possibility of illegal foreign contributions. No charges were ever filed.

There is also the case of John Edwards, a former United States senator and 2004 Democratic vice presidential nominee, who was indicted in 2011 on charges of violating campaign finance laws during his 2008 presidential campaign. The charges stemmed from allegations that Edwards had used nearly $1 million in illegal campaign contributions to conceal an extramarital affair during his campaign. Sound familiar?

Specifically, the government alleged that Edwards had received money from two wealthy donors and used it to support his mistress and their child in return for their silence. The government claimed this constituted a violation of campaign finance laws, which limit the amount of money that individuals can contribute to a campaign and require that such contributions be disclosed. Edwards maintained the payments were gifts and not campaign contributions, and therefore not subject to campaign finance laws. A jury acquitted Edwards on one count of violating campaign finance laws and deadlocked on the remaining five counts. The government ultimately decided not to retry Edwards.

The other fear which should have held back Bragg is that business records mismanagement and even campaign finance violations are typically dealt with via either administrative penalties or fines. Most of the laws Trump may have broken require some sort of intent to do wrong. In other words, Trump would have had to have taken the steps with Stormy not just for his ego or his presidential library or as some crude souvenir of virility but with the specific intent to commit harm.

Proving a state of guilty mind — mens rea — will be the crux of any prosecution. What was Trump thinking at the time? “It should be clear,” says the New York Law Journal, “Cohen’s plea, obtained under pressure and with the ultimate aim of developing a case against the president, cannot in and of itself establish whether Trump had the requisite mental state.” If DA Bragg has other key witnesses beyond Stormy and Cohen, he has not signaled as such.

The final questions are probably the most important: Bragg knows what the law says. If he understands the chances of a serious conviction are slight, why would he take the case to court? Why would he have gone to the Grand Jury at all, his predecessor and the Department of Justice having both passed on this case? No one is above the law, but that means politics must not trump clean hands jurisprudence.

If Bragg successfully navigates the politics, if he proves his case in court, then what? Trump’s “crimes” are minor. Could Bragg call Trump having to pay a fine or even doing some sort of community service during the 2024 campaign a win? It seems petty, as even a conviction would not disqualify Trump from seeking the White House (Eugene Debs ran for president while locked up).

Controversy is home turf for Trump; he is once again the center of attention and the dominant figure in his party. It sure seems like he wins politically big-picture whether he wins or loses in court. If you were Alvin Bragg, how would you answer accusations of the weaponization of the legal system to advance a political agenda?