Election aftermaths are always an opportunity for taking stock. Since the 2022 midterms, we’ve heard prominent Republicans stressing the need to revisit questions ranging from electoral strategy to how to engage the culture wars. What desperately needs discussion on the American right, however, is conservatism’s approach to economic policy.

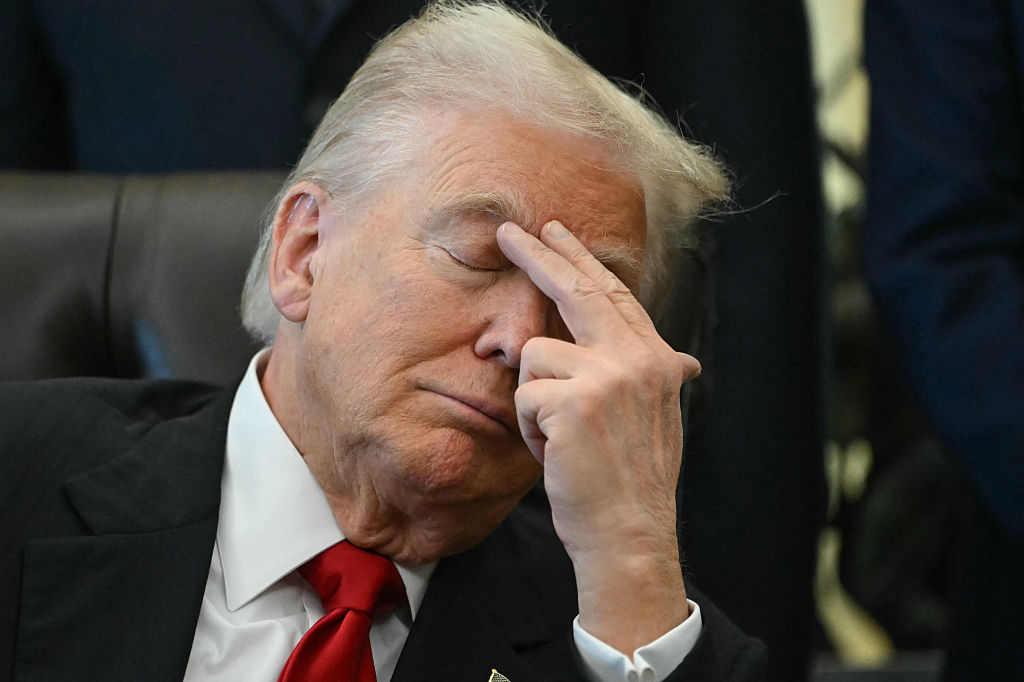

Since 2015, American conservatives have been deeply divided over economics. Conservative skepticism about markets predates Donald Trump, but there’s little question that Trump shattered the favorable views of free markets that had prevailed since Ronald Reagan’s presidency.

Trump’s protectionist rhetoric, growing worries about China, the lingering shock of the 2008 financial crisis, and concerns about widespread social dysfunction throughout America combined to open the door to support for a more economically activist state.

Attend any major conservative gathering today, and you’ll find intellectuals and Republican legislators arguing that America must embrace industrial policy to shore up the Rust Belt, preserve blue-collar jobs in manufacturing towns, and better equip America to address the China challenge.

Never mind that industrial policy has a lousy track record for delivering the outcomes promised by its proponents, or that it fuels the cronyism that infests Washington, DC. Absent more government intervention, some conservatives insist, our economy will continue going backwards and much of society will continue to suffer decay.

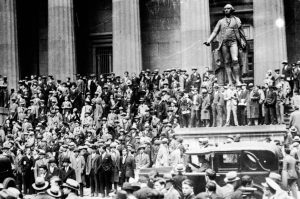

Refuting the economic case for interventionism isn’t difficult. Whether it is the blue-collar job losses that flowed from Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, industrial policy fiascos like the Obama administration’s bolstering of the Solyndra solar panel company, the New Deal’s failure to extract America from the Great Depression, or the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act’s disastrous impact on America’s share of global trade, the economic evidence is clear.

Economic nationalists are, however, adept at playing the patriotism card. They know that exhortations to “Buy American” can’t help but resonate with Americans.

Republican senators like Marco Rubio, Josh Hawley, and soon to be J.D. Vance regularly play off an equivalence between love of country and economic nationalism. The effect is to portray free market policies as more focused on utility than country, and free marketeers as Davos Man globalists enamored of borderless-world utopias.

The fact that many free-market advocates seem ill at ease touching on issues like national cohesion only fuels the sense that economic nationalists care more about America than their opponents.

It doesn’t need to be this way.

Yes, those intent on restoring American conservatism’s commitment to economic liberty must win the battle of ideas. But they must also integrate their case for markets into a wider argument about what America is meant to be. That is how ideas acquire legitimacy in conservative America.

The conservative thinker and author of The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism Michael Novak often noted that the moral and political foundations underlying American capitalism had been articulated by eighteenth-century philosophers like Adam Smith and key Founding Fathers like George Washington.

Novak used the phrase “commercial republic” to describe the polity envisaged in documents like the Federalist Papers. Federalist 11, for instance, speaks of “the spirit of enterprise” that “characterizes the commercial spirit of America.” Though allowing tariffs as a revenue source for the federal government, Federalist 35 underscores how tariffs “force industry out of its more natural channels into others in which it flows with less advantage.”

Similar ideas were expressed in George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address. It exalts free commerce’s economic and moral benefits and states a careful but firm commitment to free trade. In short, the Farewell Address’s economic outlook was far removed from that of an eighteenth-century mercantilist, let alone a twenty-first century protectionist.

The republican aspect of the American commercial republic embodied the idea of a sovereign state in which the governed were regularly consulted and government power was limited by constitutionalism and rule of law. But it also insisted that American economic life be infused with certain classical, Enlightenment, and religious virtues if America was to become what Washington envisaged in a 1788 letter to be “a great, a respectable & a commercial nation.”

Today’s America is very different from that of the Founders. Nonetheless, American conservatism has always regarded the Founding as embodying universal and timeless truths, including those concerning economics, politics, and morality.

The Founding doesn’t provide us with policy blueprints for today. But its commercial republican ideal provides those who believe in markets with a robust normative framework that reminds conservatives America isn’t supposed to be a European social democracy riddled with interventionism.

That same ideal also underscores that the greatness to which Washington referred is intended to go together with a robust commitment to economic liberty — without which America will no longer be America. Surely, American conservatives ought to be concerned about that.

Samuel Gregg is Distinguished Fellow in Political Economy at the American Institute for Economic Research, and the author of The Next American Economy: Nation, State, and Markets in an Uncertain World (2022)