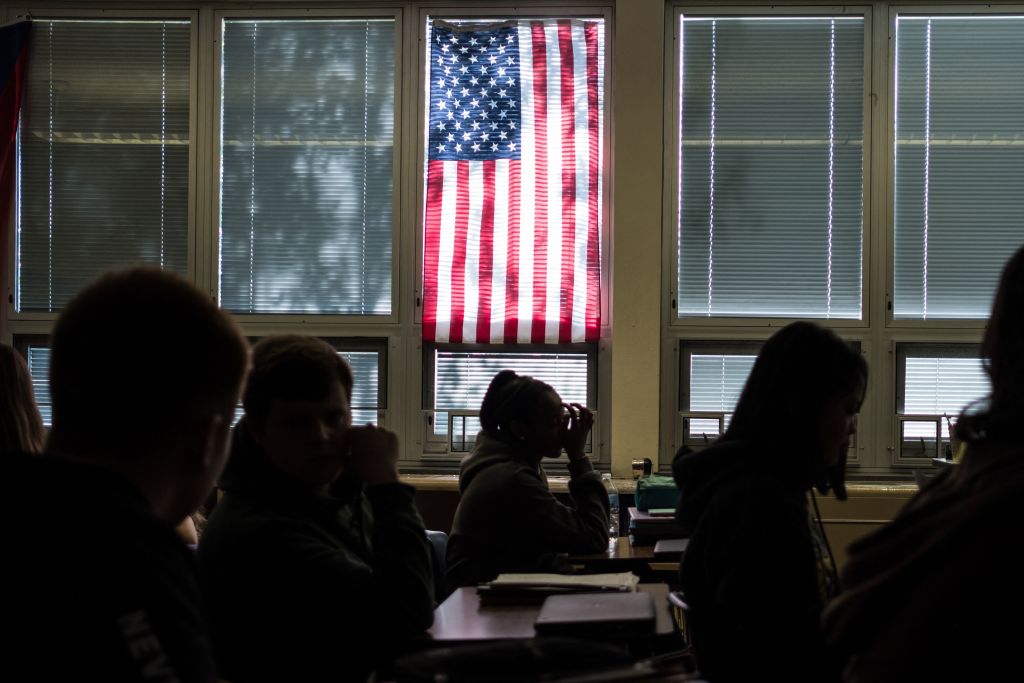

It seems that every few years America rediscovers that its children can’t read. In 2024, only 30-31 percent of eighth graders were deemed proficient in reading, and our numbers in history and math are even worse. Since 2020, no state has reported improvement across subject areas.

It’s tempting to blame “the pandemic” for these declines, but in reality, Covid only accelerated trends that were already underway. For decades before 2020, US students were struggling to reach proficiency, and the truth is that the problem isn’t today’s culture-war skirmishes over pronouns, politics and school closures. It’s the more mundane question of how children are taught to read, to count and to remember.

Let’s take phonics, for example. Until the 1980s, most teachers were trained to teach students how to read through linking letters to sounds. Taught this way, students learned rules for decoding words, so that they could sound out new words independently. The emphasis was on systematic, sequential instruction, memorization, and drilling. So if a student saw the word “cat,” they would sound out each letter and apply the process to words like “bat” and “mat.”

But by the 1990s, most teachers were trained more heavily in whole language models, which are mechanisms used to teach students to read words and sentences as a whole, focusing on context and meaning. Taught this way, students would see the word “cat” in a sentence, and would guess the word based on the context of the sentence, or based on a picture of a cat near the word.

By the late 2000s, though some states resisted, the whole language model was the norm in many elementary school classrooms. There was criticism early on, leading to some “balanced literacy” programs promising to blend whole language instruction with phonics, but in reality, “balanced literacy” usually just meant sprinkling in a few phonics lessons while relying on context guessing. Soon the science piled up, and decades of research showed that a heavy emphasis on systematic phonics is necessary for a child to learn how to read.

As states began to reinstitute phonics requirements, they realized that the teaching pipeline was stuck. Education professors were trained in whole language and balanced literacy, and taught new teachers in the same manner. Major curriculum companies also had a strong influence on what districts adopted, and had built hugely profitable programs with balanced literacy at their core. Teachers pushed back on a personal level too – no one likes being told they’ve been wronging students they care about for the entirety of their careers.

But it wasn’t just phonics and reading proficiency – similar issues showed up across educational subjects. Traditional math was standards and drill-based, emphasizing structure and singular proven methods to solve equations, but between the 1990s-2010s, new “constructivist” math allowed students to invent their own strategies with minimal direction. In the same way, traditional civics & history, which was characterized by memorizing facts and dates, was replaced with more sourcing-based lessons that ask “how do we know?” rather than “what do we know?”

The problem leading to these shifts was, in fact, ideological, but not in the way we usually think.

In the 1960s, The Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, the Vietnam War, and technological advances led to a widespread distrust of authority and tradition. Old ways, hierarchies and one-size-fits-all approaches began to be seen as oppressive, leading to a movement in the world of education that centered around the individual child and his or her self-expression, creativity and discovery. Memorization and drills soon became seen as not suited to a free, modern child, for whom education was supposed to serve in their process of self-actualization.

“Knowledge,” after all, is socially constructed, and there is no single “right” process for a child to learn. At least that’s what the educational sphere began to believe, which led to phonics rules, historical timelines, and math formulas being viewed as impositions on the child – mechanisms to inhibit equity. As a child learned to read, whole language models fit better with this world-view than did phonics drilling. Many young teachers were taught that old ways of learning like phonics could be harmful to the child because it was a power-based and limiting model.

This, then, is the pattern of the past 60 years of education: evidence-based basics like phonics, arithmetic and historical fact began to be treated as old-fashioned, and more progressive models, emphasizing meaning-making, creativity and individuality without a solid foundation became the norm. Student outcomes declined and critics called for a return to the fundamentals, but the corrections came abruptly, and teachers are now caught between what they know how to teach and what they’re suddenly expected to do.

Those blaming declining educational quality on ideology, then, are right in one sense. Not because most teachers today are ideologues, but because they teach as they were trained in programs heavily influenced by an ideology that rejects truth. Modern parents aren’t fleeing public schools because they’ve discovered a latent love of flashcards and homeschooling, but because they believe they can teach their kids more efficiently than the modern public-school teacher.

Yes, some teachers push their own politics, and that’s a problem. But it’s nothing compared to a system that treats phonics, arithmetic, and historical facts as relics. Kids can’t read – not because of one activist, but because an entire generation of educators was taught to doubt the very idea of right and wrong answers.

Why America’s schools are failing

Teachers have been trained in programs heavily influenced by an ideology that rejects truth

(Getty)

It seems that every few years America rediscovers that its children can’t read. In 2024, only 30-31 percent of eighth graders were deemed proficient in reading, and our numbers in history and math are even worse. Since 2020, no state has reported improvement across subject areas.It’s tempting to blame “the pandemic” for these declines, but in reality, Covid only accelerated trends that were already underway. For decades before 2020, US students were struggling to reach proficiency, and the truth is that the problem isn’t today’s culture-war skirmishes over pronouns, politics and school closures. It’s the…

Leave a Reply