A video has been doing the rounds in which a woman holds an iguana up to the glass window of an aquarium. A beluga whale emerges from the murk. For a brief moment two creatures whose very existence is incomprehensible to each other – who would never, in millions of years, have met but for this precise set of circumstances – come nose to nose. The whale then turns, and is gone.

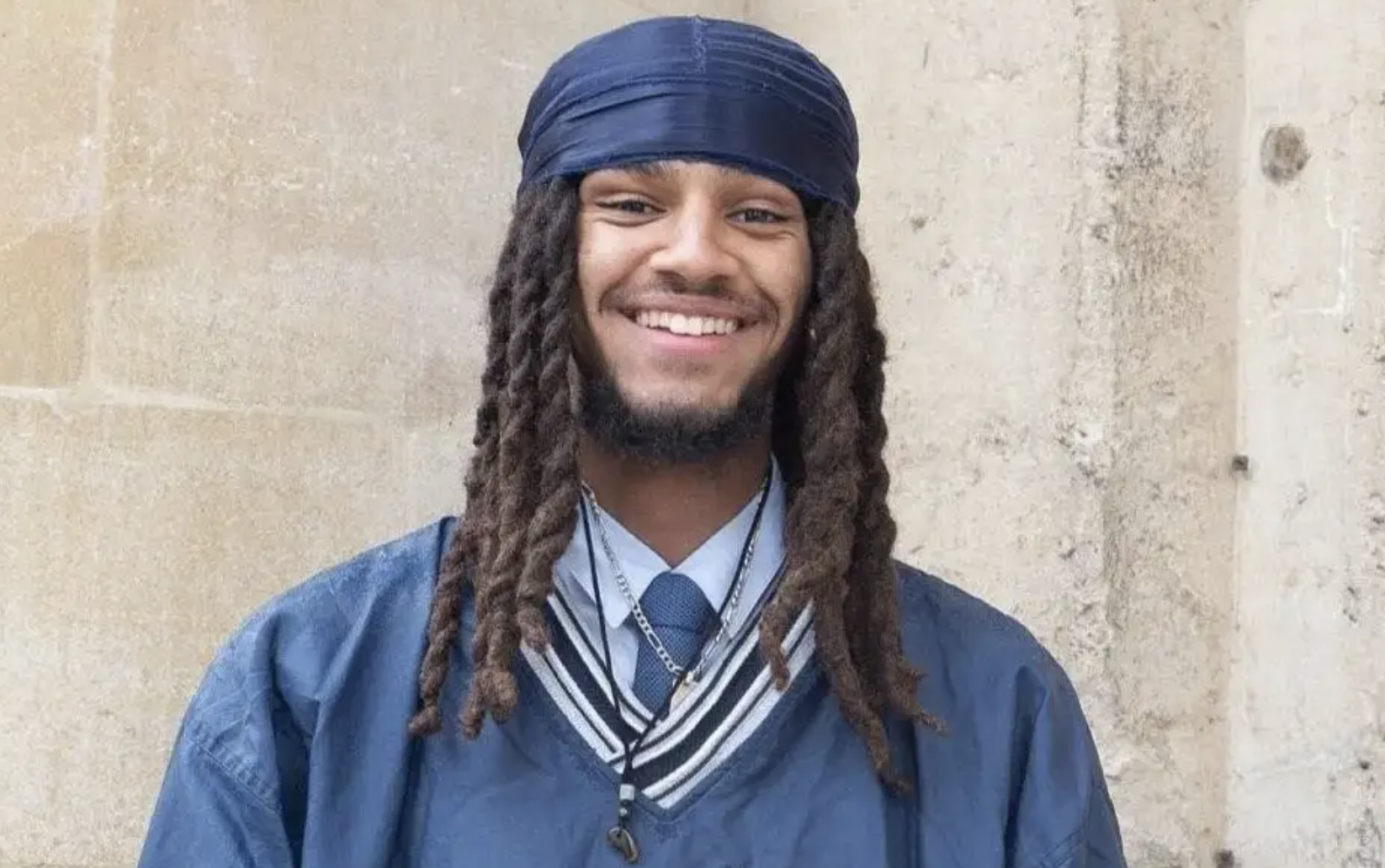

Something similar occurred on stage at the HowTheLightGetsIn literary festival in London on Sunday, where Alastair Campbell – Tony Blair’s old spin doctor – interviewed Curtis Yarvin – a “neo-reactionary” blogger, tech entrepreneur and court theorist to J.D. Vance. He has argued for a form of monarchy in which states are ruled by blockchain-enabled CEOs. Yarvin, who blogged under the name Mencius Moldbug, is in many ways an online troll come to life; he was now sat across from someone who often seems to imply that computers were invented by Putin in 2014 to spread division. The result was one of those moments in which the old society comes face to face with the new one, often to their mutual bafflement – like when Metternich met Napoleon just before the great battle at Leipzig.

“You may know that I present the world’s most popular politics podcast,” Alastair began. The two had been placed in a sort of Tiki lounge, luridly lit and framed by freestanding bits of tropical wood. Campbell was sunk deep into his chair; Yarvin was perched on the edge of his, alert like a small prairie-dwelling mammal.

“You’re a … uh … what … a computer nerd?”, Campbell asked. He was in Fleet Street bruiser mode and approached things with an air of bustle. He wanted to cut through the philosophy and get to Trump. Moldbug has always been wry about the 47th president, and his worldview looks much more to people like, say, Castlereagh, but Campbell seemed to treat him simply as a MAGA surrogate.

The jocular air didn’t last long. Asked about the virtues of strongmen, Yarvin made an offhand remark about Keir Starmer being a “weakman.” Campbell’s face hardened. “You and J.D. Vance. You come over here. And you insult our leaders.” That the mood would darken so soon was hardly surprising. Despite his reputation as a no-nonsense operator, immortalized in the character of Malcolm Tucker from the BBC TV show The Thick of It, over the past decade Campbell has developed a riven style of politics, which holds that all social antagonisms are the fault of small groups of malefactors, often involving Putin and always involving money. Such a style has little tolerance for the old cut and thrust.

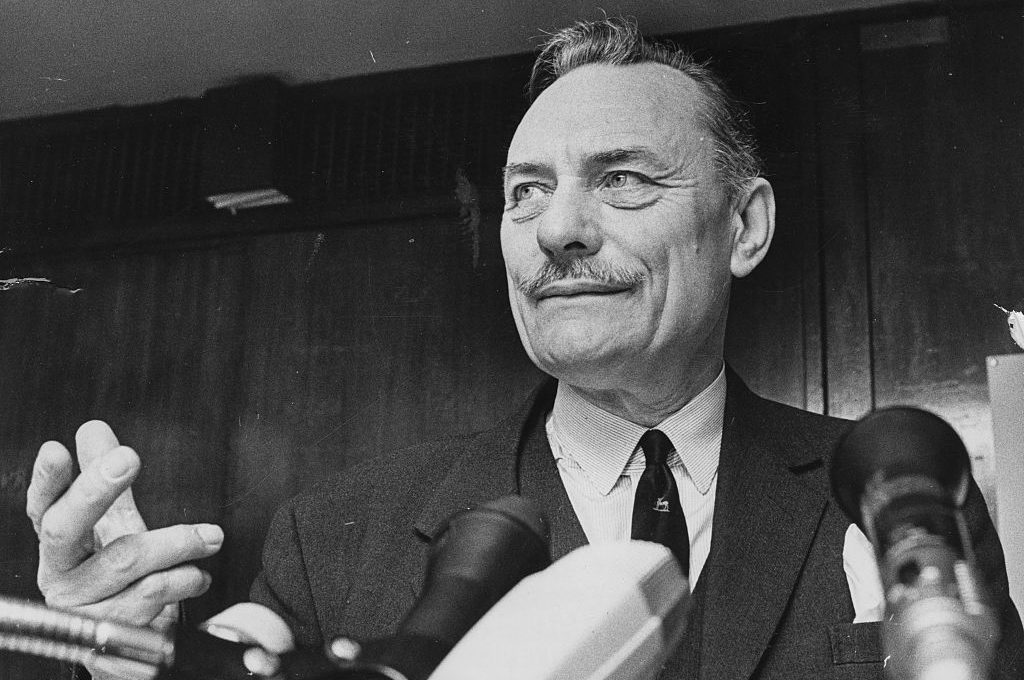

Yarvin has a roundabout manner, both in speech and in writing. His voice stops, starts and lolls from side to side. “And, uh. YEAH. I mean the thing about um, uh, Louis XIV.” On podcasts he is usually able to hold court. Here it left him open to counterattack. At one point Yarvin got stuck on a digression about whether California was a one-party state. Campbell pounced. “Yeah, you mention Frederick the Great – but do you know who admired him? Adolf Hitler.”

Campbell spoke in the New Labour argot – part HR, part baby speak

One thread Campbell seemed keen to follow was Britain versus America. “I hope you’ll advise the American public that this is not a hellhole.” For his part Yarvin kept apologising to the audience for his country having stolen Britain’s empire. Vance issued a similar mea culpa several months back.

Yet there was, in fact, a real example of Atlantic divergence on display: the great coming-apart of the English language. Asymmetric use of the internet has now split it into a series of creoles. Campbell spoke in the New Labour argot – part HR, part baby speak. Its defining trait is the bald use of concepts, Big Ideas, as if these have talismanic power. “You’re trying to divide rather than unite,” Campbell said to general applause. “The role of leadership is to bring people together and heal.”

These seemed to have little meaning to Yarvin, who answered with various forms of internet speak, making slightly wince-making references to the “Yookay aesthetics” meme. This of course did not translate well into speech, because “Yookay” just sounds like “UK.” Mutual incomprehension followed. It was very difficult for the two to converse because they were, substantially, speaking different languages.

As time went on there seemed to be a dispiriting impulse on Campbell’s part to simply get his guest on anything. Yarvin mused on how Mike Pompeo’s life as CEO of ExxonMobil was easy. Alastair lowered his voice. “Could you do it?” What exactly provoked this defense of the honor of what Campbell would definitely call “business leaders” I could not say. Another chance came when Yarvin asserted that the rule of law was a polite fiction for the “rule of men.” Campbell interjected, “Yeah, are women involved in any of this?”

Towards the end the two were no longer on speaking terms. Yarvin had by this point fallen into a sort of reverie, punctuated by high-pitched fits of laughter which reminded me of Mozart from Amadeus. “NyAHAHAHAHA.” He made a whimsical case for governance by aliens, should they prove the wisest rulers. “I’m not really into aliens,” Campbell said flatly.

Things ran out of steam after a question about whether the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) was preventing the deportation of an Egyptian terrorist who raped a woman in London’d Hyde Park, which Campbell chose to answer with a passionate send-up of the Daily Telegraph newspaper. “Does someone become British if they happen to land on the Dover coast?” Yarvin asked. Campbell only sighed. And then it was over. The two left the stage, returning to their separate worlds.

Leave a Reply