Will Saudi Arabia ever be held to account for the 9/11 terror attacks? For decades, the Kingdom has successfully parried lawsuits in the United States accusing it of providing logistical and financial support to a network of Islamic extremists who launched a global terror campaign, culminating in the September 11 attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center.

Those attacks occurred 24 years ago and since then survivors and victims of the 9/11 hijackings have had to counter not only vigorous Saudi denials mounted by their well-funded American legal team but also repeated attempts by the US government to thwart the lawsuits.

But there are signs the pendulum has begun to swing the other way. On August 28, US District Judge George B. Daniels, in a little noticed ruling in Manhattan, denied a motion by the Kingdom to dismiss the case, opening the way for a trial. In his decision, Daniels found that a small cadre of Saudi government employees tied to the consulate in Los Angeles had formed a support network for two of the 9/11 hijackers in 2000 and 2001 and probably had advance knowledge of the plot. In his opinion, Daniels raised the prospect of wider involvement by Saudi officials. Daniels ruling is the first judicial finding in the United States that the government of Saudi Arabia may have played a role in the 9/11 attacks.

A key piece of evidence in the case, what plaintiffs lawyers call an al-Qaeda surveillance video of the US Capitol, came from the United Kingdom’s Metropolitan Police Service. The Met obtained the video during a raid of the Birmingham home of a suspected Saudi intelligence operative, Omar al-Bayoumi, two weeks after 9/11.

Daniels said the evidence suggests Bayoumi, employed ostensibly as an accountant for a Saudi aviation firm, and Fahad al-Thumairy, a radical cleric based in the Los Angeles consulate, assisted two of the hijackers in advance of the attacks in their official capacity as Saudi government employees. “Thumairy and Bayoumi were not just acting as an imam and accountant,” Daniels declared. “Their employment with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia likely had some connection with assisting the hijackers.”

Nineteen al-Qaeda terrorists, 15 of them Saudi nationals, hijacked four commercial airliners in the United States the morning of September 11, 2001, and crashed them into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan and the Pentagon. A fourth plane, which the terrorists apparently intended to use to attack the US Capitol building in Washington, DC, crashed in a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after passengers revolted and rushed the cockpit.

In all, nearly 3,000 people lost their lives, including 657 at the investment firm of Cantor Fitzgerald, who were killed when American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center. Cantor’s former CEO, Howard Lutnick, now US Commerce Secretary, is a plaintiff in one of the lawsuits against the Kingdom.

Plaintiffs lawyers have been collecting evidence of Saudi involvement almost from the day of the attacks – the first lawsuit against the Kingdom was filed on September 10, 2003 – and those facts have long suggested that the Saudis provided logistical and financial support to al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups. The plaintiffs’ theory rests in part on uncontroverted evidence that the Saudi royal family and Saudi government officials, beginning in the mid-1980s funded Islamist charities that in turn supplied weapons and logistical support to mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan.

That movement later spread to the vicious Balkans war of the 1990s, which pitted indigenous Muslims and their al-Qaeda allies against local Serbs and Croats. From there, al-Qaeda quickly leapfrogged to attack other western targets including two US embassies in East Africa and the US Navy destroyer, USS Cole, culminating in the 9/11 attacks.

Regional offices of the charities employed al-Qaeda members in senior positions and these charities supplied money, travel documents, arms, safe houses and other assistance to al-Qaeda cells, the plaintiffs allege. Absent the assistance of Saudi government funded charities, a half dozen of which were designated as terrorism supporters by the US Treasury Department, al-Qaeda and bin Laden never could have mounted the logistically complex 9/11 operation.

So alarmed were US government officials by the role of the Saudi charities in funding international terror that then-vice president Al Gore met privately in 1999 with then crown prince Abdullah in the White House to ask for assistance in tracking down terror groups based in the Kingdom. Abdullah agreed to put senior US intelligence officials with their Saudi counterparts, but US officials said nothing came of it.

“We went to the Saudis as a government, showed them what we had, asked them for more information, warned them of what might take place and ultimately nothing happened,” said Jonathan Winer, then deputy assistant secretary of state for international law enforcement.

Central to the lawsuits against the Kingdom are reports that emerged within days of the attacks that Bayoumi and Thumairy, the Saudi consular official, assisted Nawaf al-Hamzi and Khalid al-Mihdhar, the first 9/11 hijackers to arrive in the United States, getting settled in southern California in January of 2000.

Bayoumi’s ostensible employment as an accountant was with a Los Angeles based Saudi aviation company named Dallah Avco, in a government funded position. While Bayoumi drew a salary, fellow employees told investigators he only rarely showed up for work. He did, though, have multiple contacts with the hijackers, along with Thumairy, helping them find an apartment and co-signing a lease for a rental in San Diego, and arranging for them to take flying lessons and learn English.

When interviewed by the FBI shortly after 9/11, Bayoumi said he had met the hijackers by chance in a Middle Eastern restaurant in Los Angeles on February 1, 2000, near the Saudi consulate, where he had traveled to clear up a visa problem. He claimed to have taken the initiative to introduce himself to the hijackers when he heard them speaking an Arab dialect common in the Persian Gulf and felt it was his duty as a fellow Muslim to help them get settled.

This claim was dismissed early on by FBI investigators who concluded that Bayoumi’s luncheon meeting with the hijackers had been planned and that he likely was a Saudi intelligence operative with links to al-Qaeda. “(Bayoumi) acted like a Saudi intelligence officer, in my opinion,” an FBI agent told congressional investigators. “And if he was involved with the hijackers, which it looks like he was, if he signed leases, if provided some kind of financing or payment of some sort, then I would say there might be a clear connection between Saudi intelligence and UBL (Osama bin Laden).”

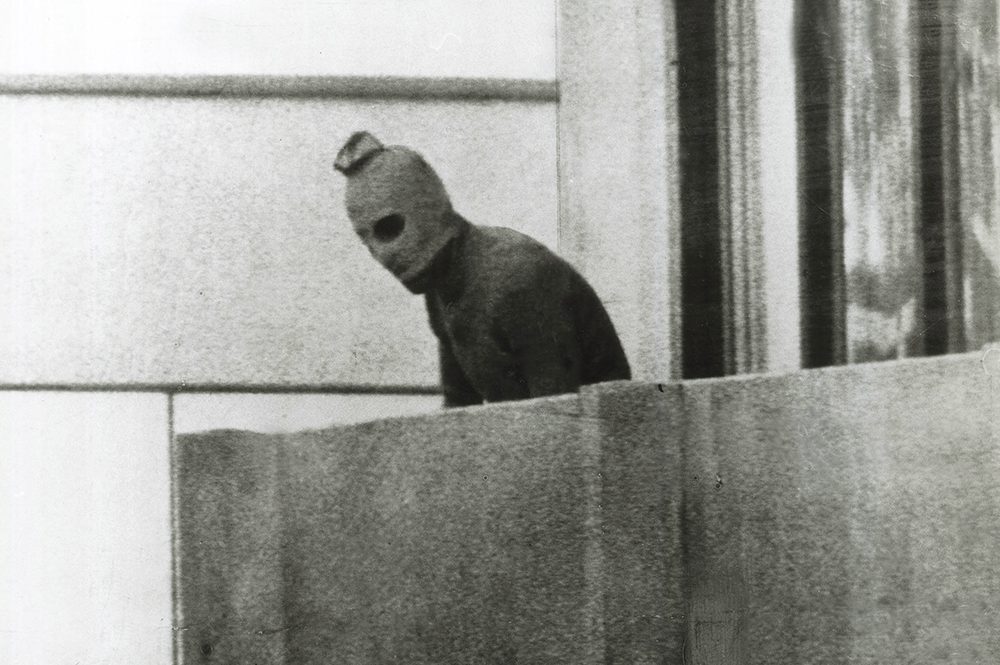

Bayoumi moved to England before 9/11, but soon after the attacks FBI agents who had picked up his trail in southern California, alerted British authorities of his potential role and the Met Police searched his Birmingham home. Among the items taken from the house was a video recording Bayoumi made of the US Capitol building in 1999 along with the Washington Monument and other landmarks. Also confiscated was a drawing of an airplane with a calculation that experts for both the FBI and plaintiffs lawyers later concluded was a mathematical formula showing the rate of descent necessary for an airplane to collide with a target on the ground.

While he made the video, Bayoumi was accompanied by two Saudi embassy officials from the Ministry of Islamic Affairs, a branch of the Saudi government staffed at the time by radical clerics whose role was to propagate a militant form of Wahhabi Islam that vilified the west. In the video, Bayoumi takes pains to note the Capitol’s main entrances and points out locations of the capitol’s security staff.

Former acting CIA director Michael Morrel, and other former US intelligence officials have described the video as a casing film made in preparation for a terrorist attack. “No doubt in my mind that al-Qaeda tasked him to do this casing video,” Morrel said in an interview with CBS news.

One of the more salient aspects of the aftermath of 9/11 is the degree to which the United States government has sought to conceal what it knows about the origins of the plot, a tactic that has frustrated efforts by the plaintiffs lawyers to get at the truth while greatly benefiting the Saudis. The stonewalling began with the administration of President George W. Bush, which insisted on classifying and keeping from public view portions of the first congressional investigation, the so-called Joint Inquiry, raising questions about Bayoumi and the potential role of the Saudi government.

The late Senator Bob Graham, who co-chaired the investigation, then went so far as to accuse Bush of protecting the Kingdom because of Bush family ties to the oil industry and Saudi royals.

The equivocations and evasions continued through each succeeding administration. The FBI, for example, has been in possession of the Bayoumi video of the Capitol building since 2001, but failed to turn it over to not only plaintiffs lawyers but also the 9/11 commission. The plaintiffs only were able to access the video when the Met Police agreed to give it to them in 2022.

Some of the foot dragging at times has resembled theater of the absurd. Early in the case, when plaintiffs lawyers requested the Justice Department make public a copy of the Interpol bin Laden arrest warrant, the answer they got back was the warrant was protected by privacy rules and that department couldn’t release it without bin Laden’s permission.

At other points, the government obstruction was of far greater import. In 2009, then US Solicitor General Elena Kagan, now a US Supreme Court Justice, filed an amicus brief in the litigation asking the Supreme Court not to hear an appeal of a lower court decision dismissing the case against the Kingdom. Kagan argued there was no persuasive evidence of Saudi government involvement, even as the FBI continued to pursue evidence Bayoumi was a Saudi intelligence operative with possible links to al-Qaeda. The Supreme Court, heeding Kagan’s request, declined to hear the matter.

Later, in 2016, the Obama administration lobbied heavily against legislation intended to aid the 9/11 victims by expanding the basis for suing foreign governments that foment terrorism. Administration officials warned the Saudis would withdraw upwards of $750 billion in assets from US financial institutions if the bill became law. Obama vetoed the measure after both the House and Senate passed it overwhelmingly. Congress overturned the veto and the bill became law.

That measure, the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act, clarifies the US State Department need not designate a foreign government a terrorism supporter as a condition for being sued in US courts, a requirement that had hampered the 9/11 lawsuits. It also makes clear that not all of the tortious conduct must to take place in the United States.

The dire scenarios depicted by the Obama administration never came to pass, while the measure gave new life to the plaintiffs’ litigation and set the stage for Daniels’ groundbreaking decision on August 28.

Now that the lawsuits seem to be headed for trial, 9/11 victims and their families, along with the nation as a whole, may finally get answers to questions about Saudi Arabia’s involvement that have been swirling around the case since the beginning.

Leave a Reply